“Thrilla in Manila” turns 50 today, October 1. It was the fight that punched my hometown Cubao’s place in history.

All roads lead not to Rome, but to Cubao.

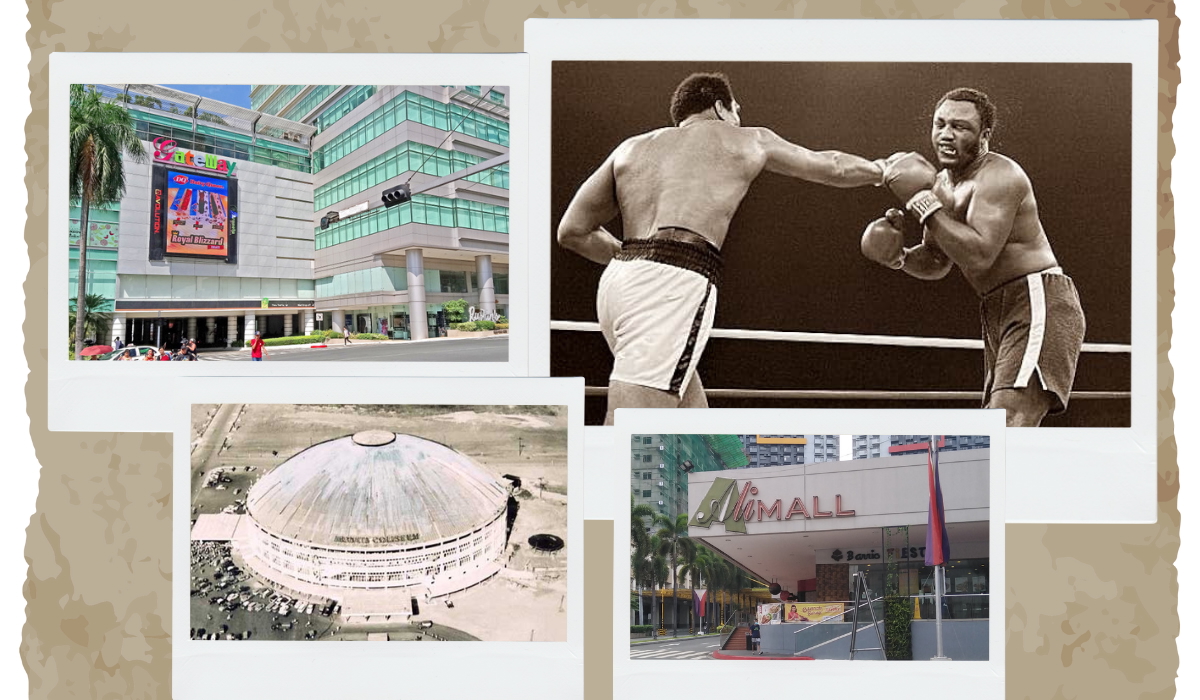

This may not make sense to most people, but for those of us who live here, we’ll insist that it’s the center of Manila’s north and south—despite what the maps or the skeptics say. With iconic landmarks Araneta Coliseum and Ali Mall, Cubao has always been a place that welcomes everyone: a hub for hobbies and expression, and for many of us, an extension of home.

The old Cubao luster may have faded, but its spirit remains. Half a century later, history loops back—a Marcos once again sits in Malacañang, and his First Lady traces her lineage to the Araneta clan.

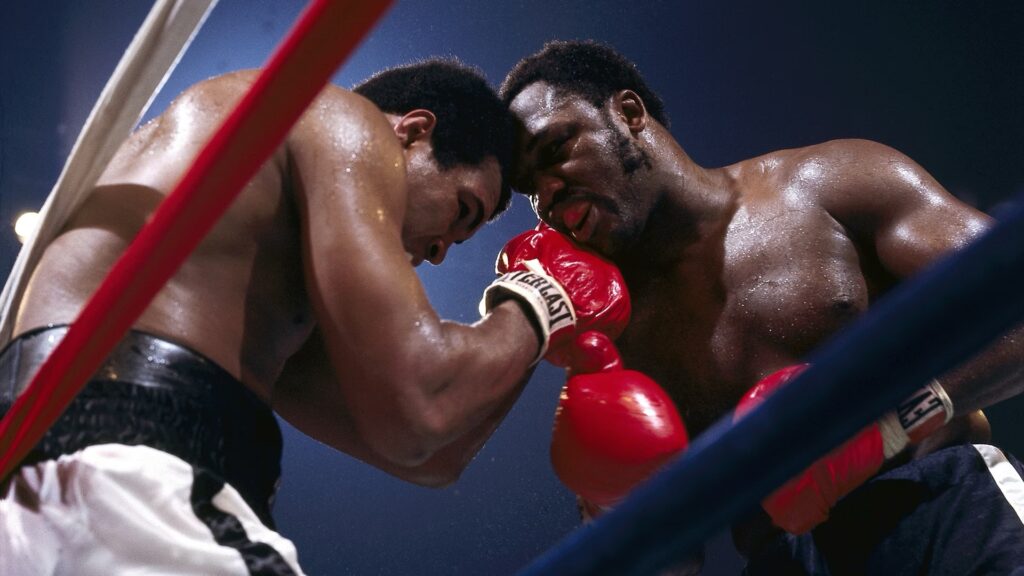

Strolling around what’s now called Araneta City, I begin my nostalgic trip down memory lane. First stop: Ali Mall, the namesake legacy of boxing’s all-time great, Muhammad Ali. The mall, which claims to be the first enclosed, fully air-conditioned, multi-level shopping mall (Crystal Arcade’s art deco walls might disagree), was built by businessman Jorge Araneta in honor of the former undisputed heavyweight champion.

Today, only a small commemorative area remains, featuring a ring and standees of Ali and Frazier paying homage to their historic bout.

A fight that made the world look to Cubao

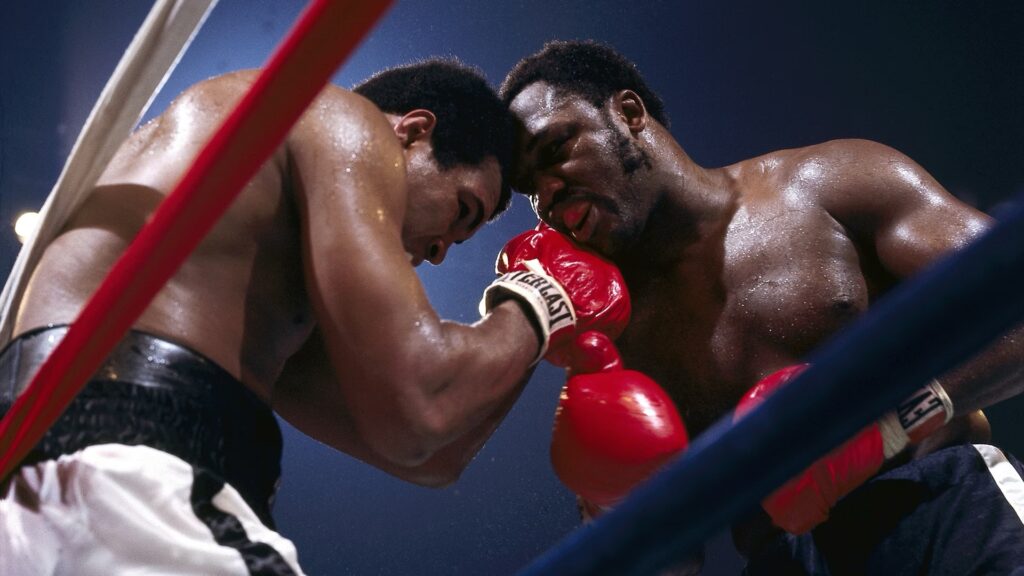

Marking its 50th anniversary this month, Thrilla in Manila in 1975 was the third and final clash between two of boxing’s greatest heavyweights, Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Held at the Araneta Coliseum in Cubao, Quezon City, this momentous bout—between former friends turned fierce rivals—was the stuff of boxing mythology.

Widely regarded as the pinnacle of boxing’s golden age, the fight transcended the sport. Its undertones went beyond the ring, reflecting its era and leaving an indelible imprint on both Philippine culture and global history.

For one morning in 1975, the world’s attention turned to the Philippines, eager to witness two men in their prime. Meanwhile, the host country was deep in the grip of Martial Law, three years after President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. placed the nation under military rule.

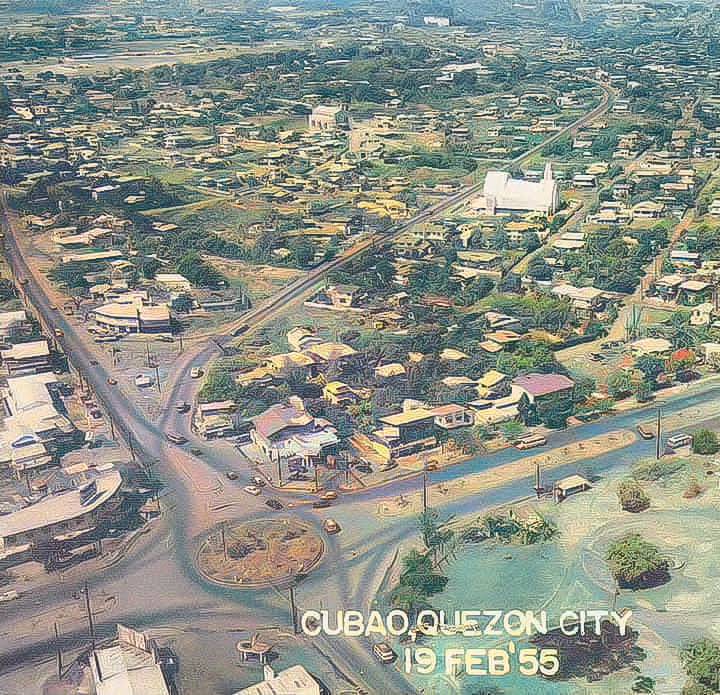

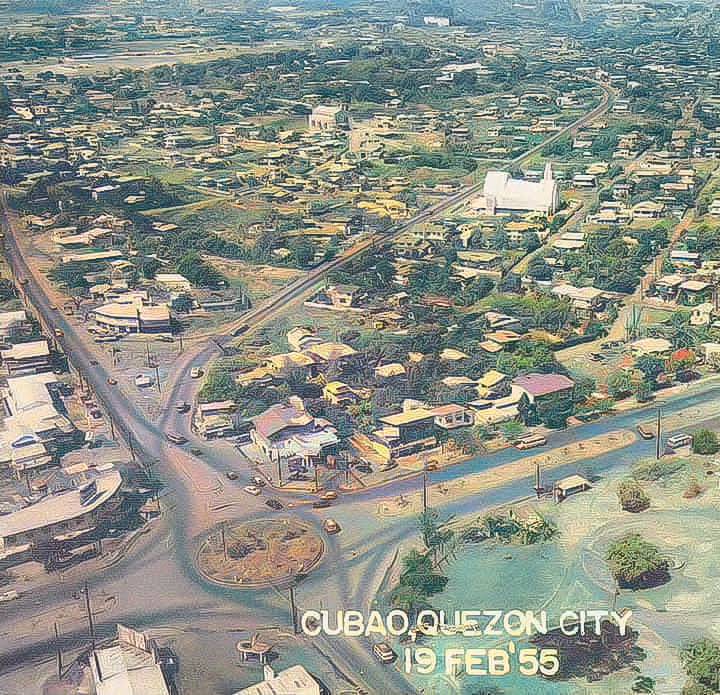

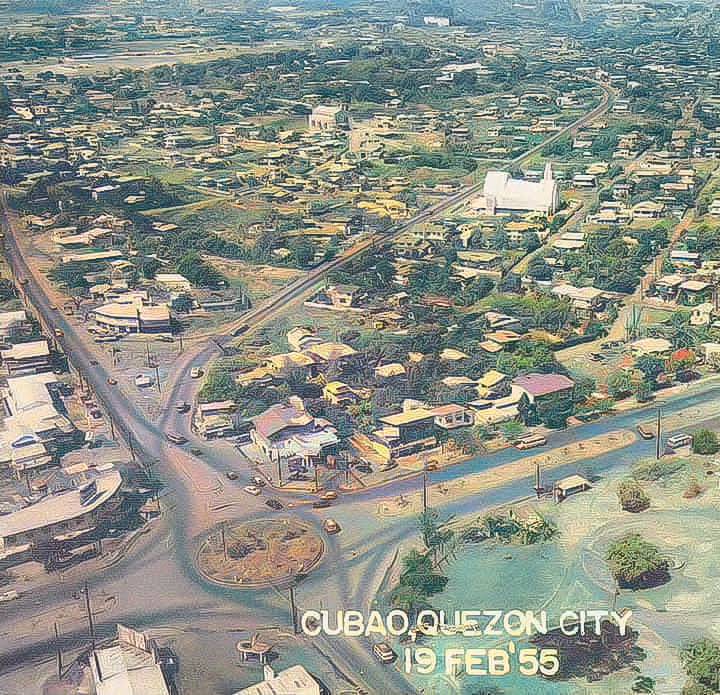

And this all unfolded in Cubao—once a barren field of cogon grass and old American radio towers.

From cogon field to Cubao

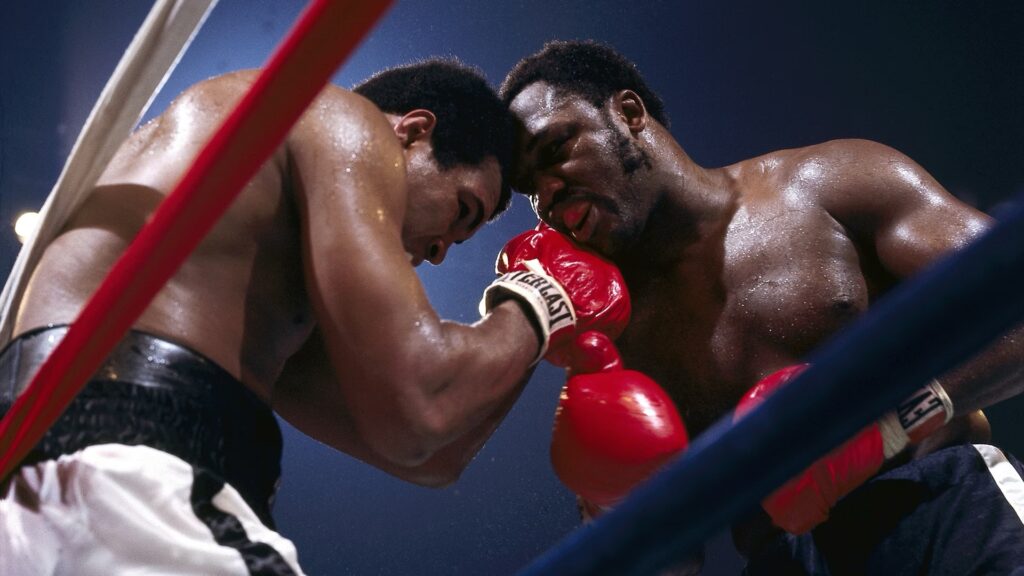

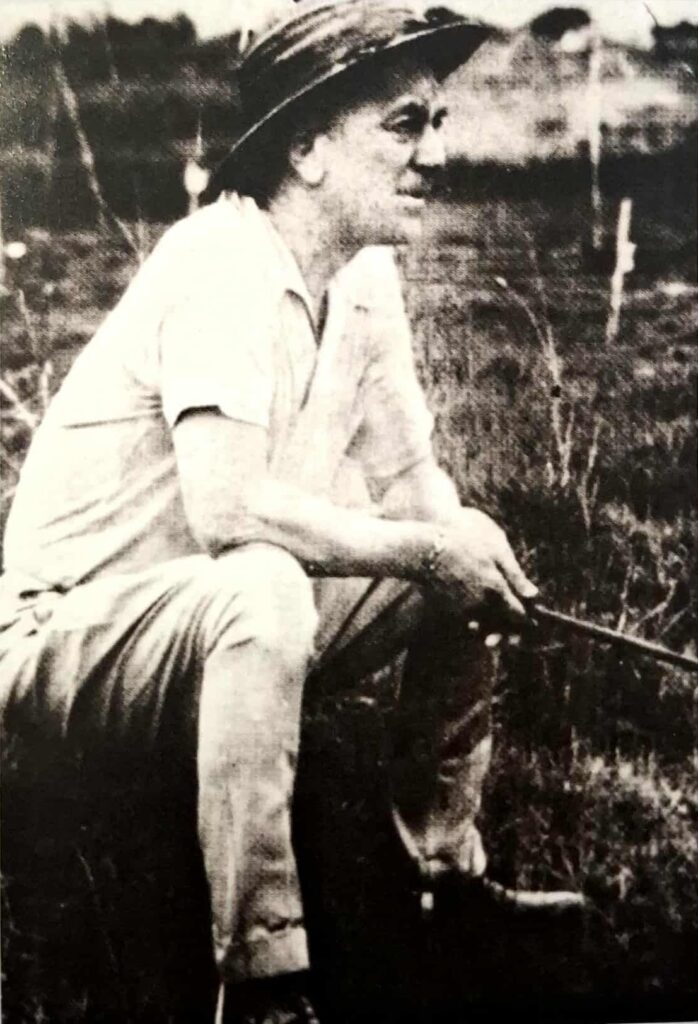

Cubao is a relatively young commercial hub. Unlike Quiapo, which once served as the gateway to Intramuros during Spanish colonial rule, or Binondo, the world’s oldest Chinatown established in 1584, Cubao rose quietly in the 1950s—five years into Manila’s slow recovery from the devastation of World War II.It was around this time that J. Amado Araneta—patriarch of the Araneta family and a former sugar planter—visited Rome after losing his home in the war. Inspired by the grandeur of the Colosseum, he dreamt of building something just as monumental, but for Filipinos.

The timing was perfect. In 1938, President Manuel L. Quezon had purchased 1,529 hectares from the Tuason estate as part of his vision to build a new modern capital outside Manila. By the 1950s, according to Filipino writer Erwin E. Castillo in Hatao, Cubao! (2008), Highway 54 (now EDSA) and Aurora Boulevard conveniently converged into the hilly areas of Cubao—making it the perfect nexus for a growing city.

In 1955, after acquiring land owned by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), Amado Araneta advanced his vision of a coliseum by setting out to create a large indoor arena to rival the likes of Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Finally, the Araneta Coliseum opened its doors on March 16, 1960. Its first event was headlined by a world championship boxing match between Filipino Gabriel ‘Flash’ Elorde and American Harold Gomes. The Filipino Flash dazzled nearly 23,000 fans in attendance inside the brand new area, as he routed his rival to clinch another world championship for the Philippines by knocking down his opponent six times—twice in the second round, once in the third, once in the fifth, and twice in the seventh.

The Coliseum became an instant hit. Nicknamed “The Big Dome,” it was lauded for its engineering feat—boasting the world’s largest clear-span dome without a single obstructing post.

Fifteen years later, it would host a match that once again placed Cubao in the global spotlight.

Related story: Filipina boxers Nesthy Petecio and Aira Villegas bring home bronze

Related story: He could be the best of us: Cebu-born Hyder Amil is a trailblazer in top-level mixed martial arts

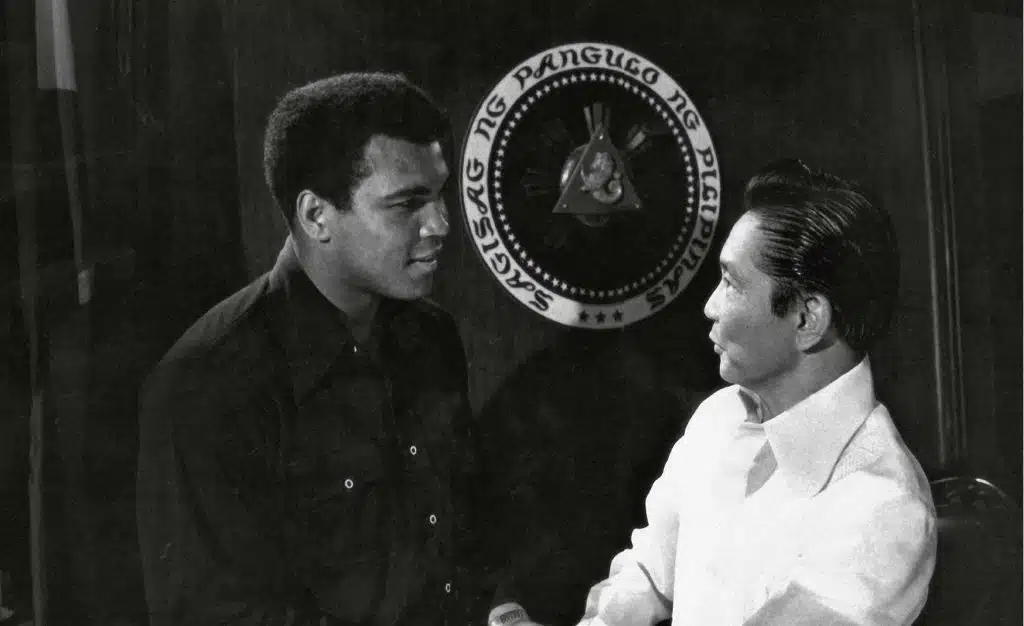

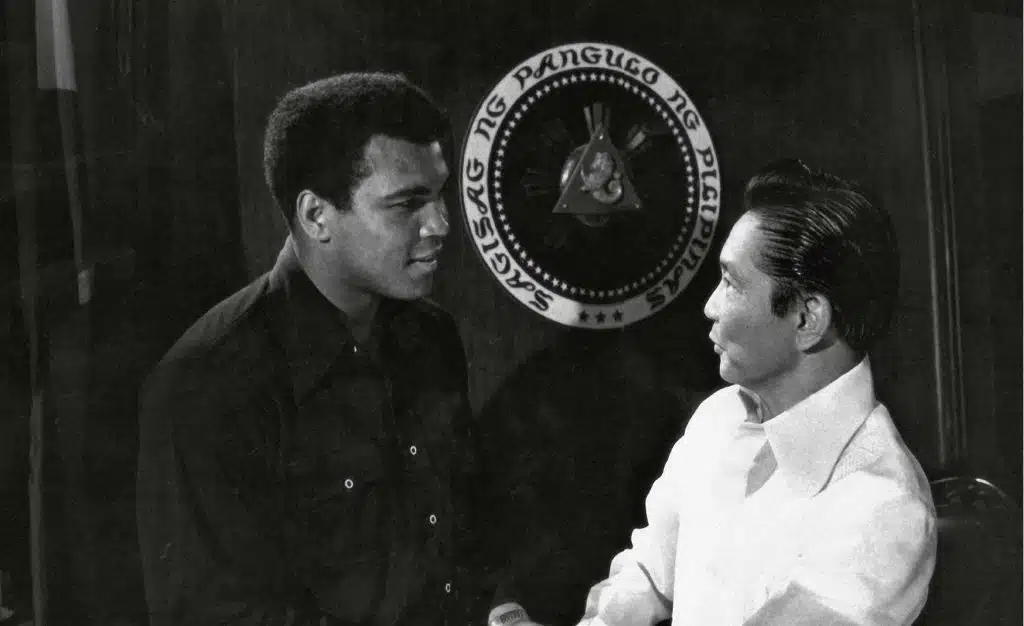

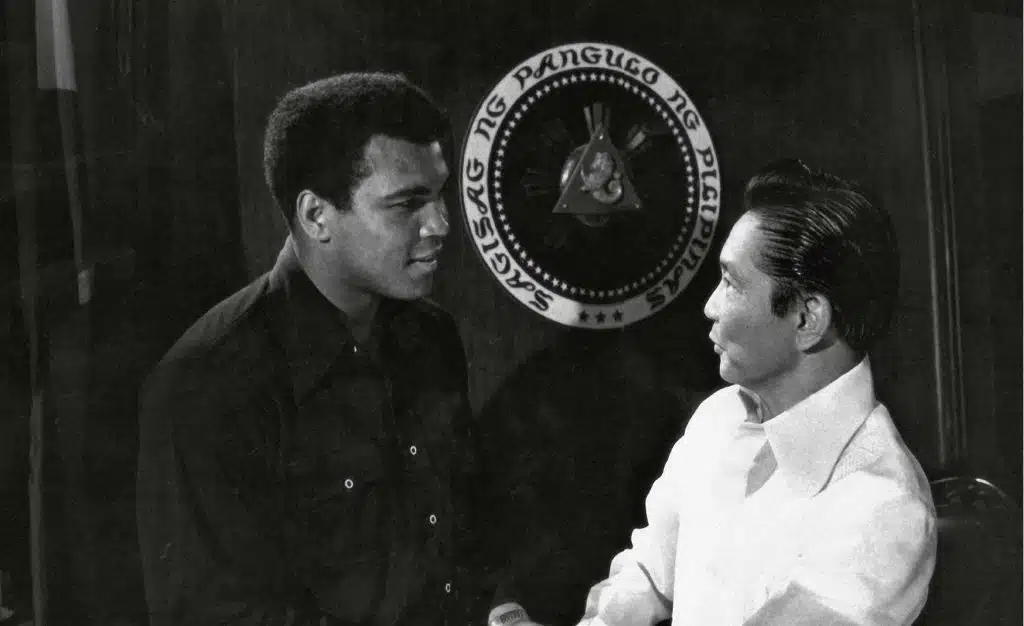

Marcos Sr. borrows the Araneta Coliseum

Hosting the Thrilla in Manila in 1975 was part of President Marcos Sr.’s broader effort to project control and stability during Martial Law. Just a year earlier, the country hosted the Miss Universe pageant at the Folk Arts Theater. When it came time for the fight, there was only one venue worthy: the Araneta Coliseum.

The administration’s only condition was to temporarily rename it the Philippine Coliseum, to match the fight’s catchy global title.

Thrilla in Manila was a convergence of spectacle and symbolism—a dictator’s showcase, a global distraction, and a milestone for a district once filled with cogon grass and radio towers.

In a recent interview with The Atlantic, Jorge Araneta recalled with humor: “At least they gave it back. Some people would have kept it.”

Like a modern Roman emperor staging a gladiatorial spectacle, Marcos was willing to pay the price. Ali was promised $4.5 million—including a $3 million grant from the Philippine government—at a time when a Filipino laborer reportedly earned just P2.44, according to this report of the World Bank in 1972.

The late sports journalist Ronnie Nathanielsz, who served as Ali’s liaison during his stay, captured the magnitude of the event in a 2016 CNN interview: “It was a big deal for the Philippines—especially for Marcos, who said, ‘We’re doing this fight because we want to show the whole world there is law and order, and that the people are happy.’”

In the ring, Ali prevailed—barely. After 14 brutal rounds, Joe Frazier’s trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight, refusing to let his exhausted fighter come out for the 15th.

For Cubao, and for the Araneta family, it was a defining moment. After the fight, the Aranetas hosted Ali for lunch. To lift his spirits after the grueling bout, Jorge Araneta told him he would name a mall in his honor.

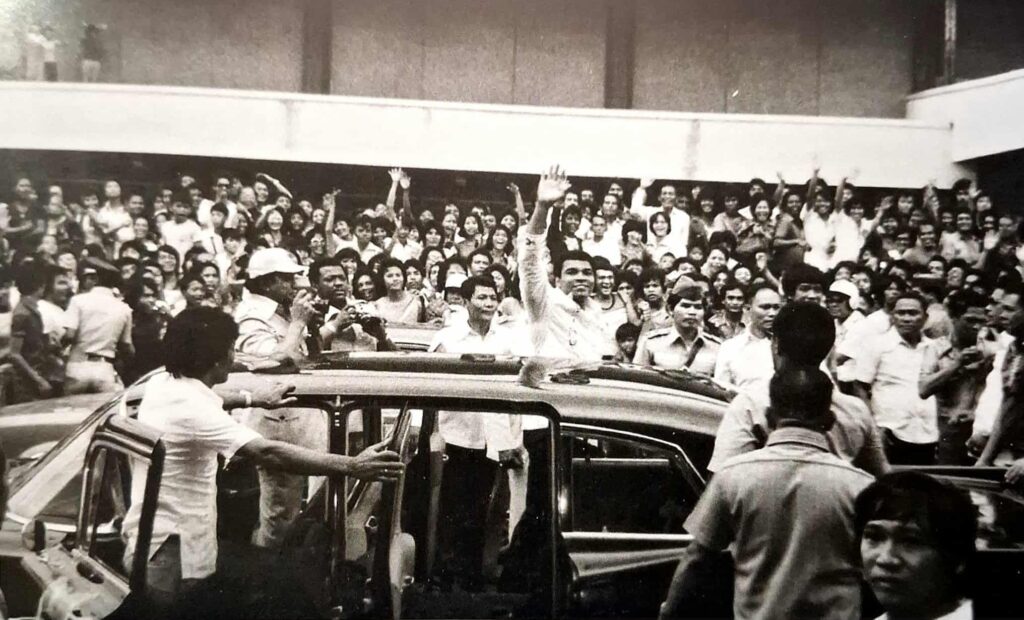

True to his word, a year later, Ali returned to the Philippines for the inauguration of Ali Mall on June 30, 1976—immortalized in the 2009 book The Big Dome and Beyond by Alfred A. Yuson and Paulo Alcazaren.

Lasting legacy

Walk around Araneta Center today and the echoes of that era still linger—if you know where to look.

Many establishments have come and gone, their façades modernized, their names changed. The old four-story National Bookstore still stands, though only two floors remain open. The New Frontier Cinema—briefly renamed Kia Theatre—still brings memories of my first movie, Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace in 1999, when I was five.

Today 50 years ago, everyone witnessed history unfold. Muhammad Ali wanted to avenge his first-ever career loss when Joe Frazier won against him in their first fight in 1971, after Ali was sent to the canvas following Frazier’s signature power left hook in 1971, ultimately losing the fight via decision.

Frazier wanted to prove he wasn’t just a paper champion. He had endured all the antics of Ali, whom he called Cassius Clay, the latter’s government name before converting to Islam. The insult infuriated the enigmatic Ali to no end.

Today, thousands still flock to the Smart Araneta Coliseum, now framed by high-rise condominiums and shopping centers. The old Cubao luster may have faded, but its spirit remains. Half a century later, history loops back—a Marcos once again sits in Malacañang, and his First Lady traces her lineage to the Araneta clan.

Thrilla in Manila was more than a boxing match. It was a convergence of spectacle and symbolism—a dictator’s showcase, a global distraction, and a milestone for a district once filled with cogon grass and radio towers.

Related story: The thrill and agony of watching EJ Obiena chase his Olympic dream

Related story: From grit to gold and glory: The year in Philippine sports

Related story: One hundred years of fortitude