From teaching posts to book deals and the uphill climb of screenwriting, the awards alter career paths but never in the same direction for everyone.

“This is never gonna happen again.” This is one of the funniest bits in Olivia Colman’s uproarious, instantly classic acceptance speech at the 2019 Academy Awards where she won the trophy for Best Actress in a Leading Role for The Favourite, a darkly comedic period drama set in the 18th century about two women who scheme and manipulate to become the favorite of a queen (Colman) with mental health issues.

I probably would have beaten her to using the quip by a good three years if the Palanca Awards had acceptance speeches.

The Palanca Awards are considered the Pulitzers of the Philippines. But because I consider myself as belonging more in the film industry, I think of them as the Oscars of the local literary world. The awards were established in 1951 by heirs of Chinese-Filipino businessman and philanthropist Carlos Palanca Sr. According to the foundation’s website, the Palancas aim to “recognize, encourage, and incentivize excellence in Filipino literature” and to “act as a treasury of the nation’s literary gems.”

There are currently a total of 20 categories including several differentiated by languages and age range. Most of them are meant to be read and experienced entirely from the written page—poetry, short story, essay—while plays and screenplays form part of the larger artistic platforms of theater and film.

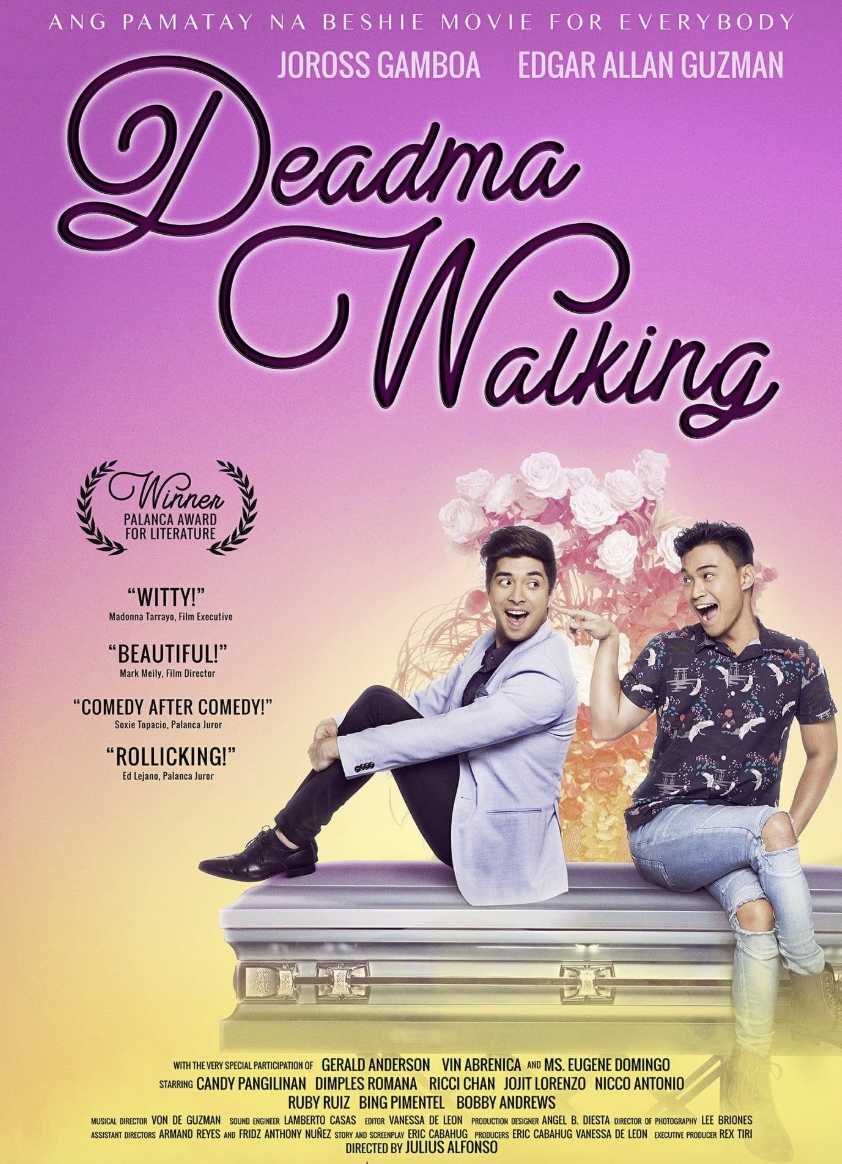

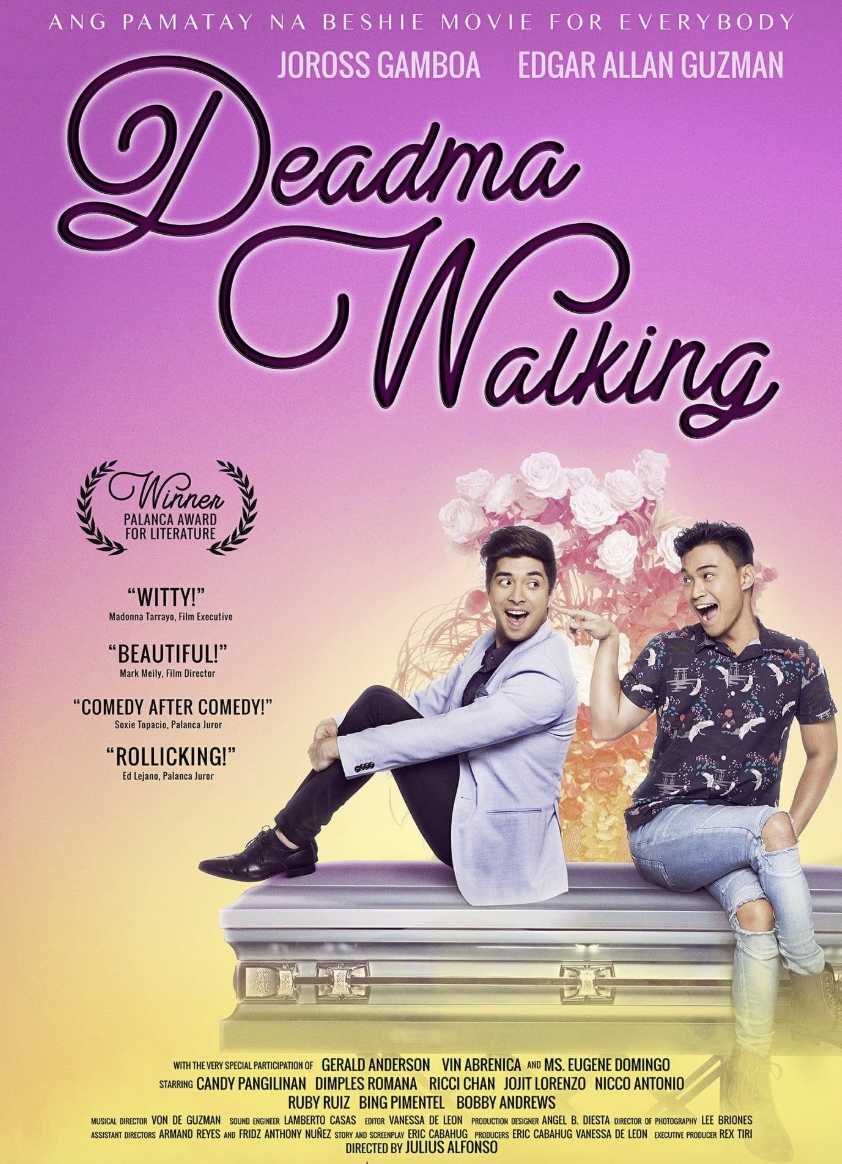

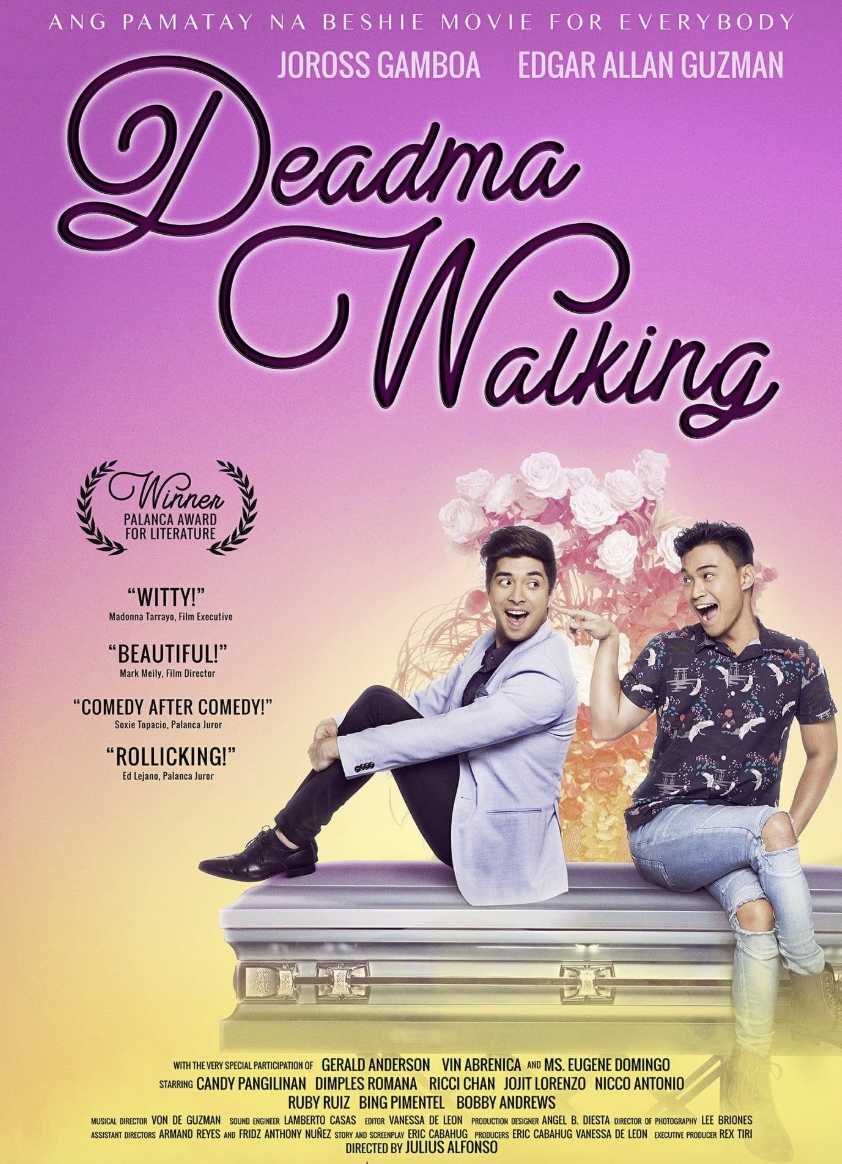

After a couple of unsuccessful entries at the annual competition, I finally won a Palanca award in 2016, clinching 2nd Prize in the Dulang Pampelikula (Screenplay) category for my own dark comedy Deadma Walking, which is about a terminally ill gay guy who schemes to fake his own death, wake, and burial with the help of his gay best friend, primarily to hear what people have to say about him.

That victory came as a shock. Although I entered the script upon the recommendation of an award-winning film director friend who had read it and had previously served as a Palanca judge, I did not see it having a good chance of winning. Deadma Walking is so unserious, so flighty, so campy, and, well, so gay that I thought it was not at all the kind that ends up getting the title of “Palanca winner”—serious, substantial, socially conscious, straight-laced.

I was convinced it was a fluke and that it will never happen again.

Published authors and those eyeing to get a book deal would almost certainly say a Palanca laurel makes writers and their works more attractive to publishers. That’s mainly because it makes them more attractive to readers.

The awards committee sent out notices to the winners via text messages, emails, and snail mail in June 2016. By the time the awards night came in the first week of September, I had already known that I had won for about three months. Still, for most of the night I remained incredulous that I was actually there as an awardee, literally in the same room as some of the biggest names in Philippine literature in one of the most important nights in the industry every year.

While I did not exactly feel like a fish out of water, thanks to several guests from the local movie industry that I knew, the affair had tinges of the surreal, the awkward, the thrilling, and the “once-in-a-lifetime.”

Related story: Palanca winners reveal secret to outstanding work. Here are 54 of this year’s best writers

Related story: The POST Chats: Award-winning writer Kenneth Yu on writing short fiction, recommended reads

From gay comedy to socially conscious

Apparently the universe knew something I didn’t. I have just won my second Palanca, almost a full decade later. This time it’s for a historical drama titled Ang Birheng Ipinagkanulo (The Virgin Denied), about the controversial alleged Marian apparitions in Lipa, Batangas in 1948. It’s serious, substantial, socially-conscious, and straight-laced. In short, a “perfect” Palanca piece, to my mind at least.

This time I got the first prize and it came with a big gold medal. This time I was rather chill at the awards ceremonies. That’s largely because in the almost-decade that has passed since 2016, I’ve found myself exploring more of the local literary world.

Since 2016 I have seen two works of mine get published as books: Deadma Walking in 2017, which became a certified Top 10 Philippine Fiction bestseller at National Book Store for five months, and my first novel, the romance-comedy Destination: Pag-ibig, the following year. I’ve also met and actually worked with, through my posts as Creative Manager in Viva Entertainment and Editorial Director in VRJ Books, several authors including literary luminaries such as National Book Awards laureate Bob Ong and four-time Palanca winner Eros Atalia.

Modesty aside, the recent awards night felt more like a homecoming and a reunion of sorts, even though I still consider myself, first and foremost, a denizen of the film industry.

What happens after the Palancas?

What does winning do for a writer’s career? The answer depends on who you ask. Winners with careers in the academe—poets, essayists, short story writers, novelists—would most likely echo what Dr. Ruth Elyna Mabanglo, Palanca winner more than 20 times over and guest of honor at this year’s ceremonies, said in her speech, “The Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature opened many doors for me.”

The first of those doors was getting hired as a visiting professor at the University of Hawaii in the early part of her career. She went on to teach there for 30 years in which she was able to do a Bachelor of Arts degree program in Filipino and Philippine Literature—the first of its kind outside the Philippines.

Published authors and those eyeing to get a book deal would almost certainly say a Palanca laurel makes writers and their works more attractive to publishers. That’s mainly because it makes them more attractive to readers. It’s like—for lack of a better, more current example, and without meaning to lessen it—a Michelin star for book lovers.

It’s not a guarantee, though, of a long-lasting career as a published author in the Philippines, much less one that’s financially rewarding. While the local publishing industry has been experiencing a youth-powered boom since the early 2000s with the rise in popularity of fan fiction and comic books, the market has not grown big enough to sustain professional career authors.

Readers have something in common with theatergoers; many are quite open to fresh voices, new narratives, and unconventional storytelling styles that the Palancas tend to champion. Great for them.

Screenwriters have it tough because the local film industry is less enamored with the Palancas. So much less. Filipino moviegoers in general aren’t as adventurous as their counterparts in the literary and theater worlds.

Screenwriters, though, have it tough because the local film industry is less enamored with the Palancas. So much less. Filipino moviegoers in general aren’t as adventurous as their counterparts in the literary and theater worlds. They would rather stick to formulas, to the familiar, to what they already know and have been accustomed to watching on the big screen. Especially for Filipino films.

No one can blame them. Movie ticket prices have risen so high most viewers can afford to watch only a handful of films in a year. So, they would rather play safe rather than risk not getting their hard-earned money’s worth. And many equate money’s worth with sheer entertainment — laughs, tears, thrills, frights. The serious, substantial, socially conscious, and straight-laced don’t cut it.

This explains why very few Palanca-winning screenplays get produced and, of those that do, much fewer fare well at the box-office. In fact, in the last dozen years, only That Thing Called Tadhana, 3rd Prize in the 2014 Palancas, and Deadma Walking made dents at the tills. And it’s not even because they had the Palanca stamp; it was because they fall into the popular genres of romance comedy and gay comedy, respectively.

Which brings us back to Colman. The Philippine movie industry can only dream of a time when much-decorated non-mainstream fare like The Favourite or typical “Palanca” films regularly become audience favorites.

In any case, writers have the Palanca Awards to thank for the inspiration and aspiration, the actual recognition and validation, the honor, not to mention the lifetime bragging rights, whether winning happens just once or it happens again.

Related story: Meet this writer who’s shining the spotlight on the Filipino-Canadian experience

Related story: From my shelf to yours: Introducing a literary support group