“Broken things have their own stories to tell.”

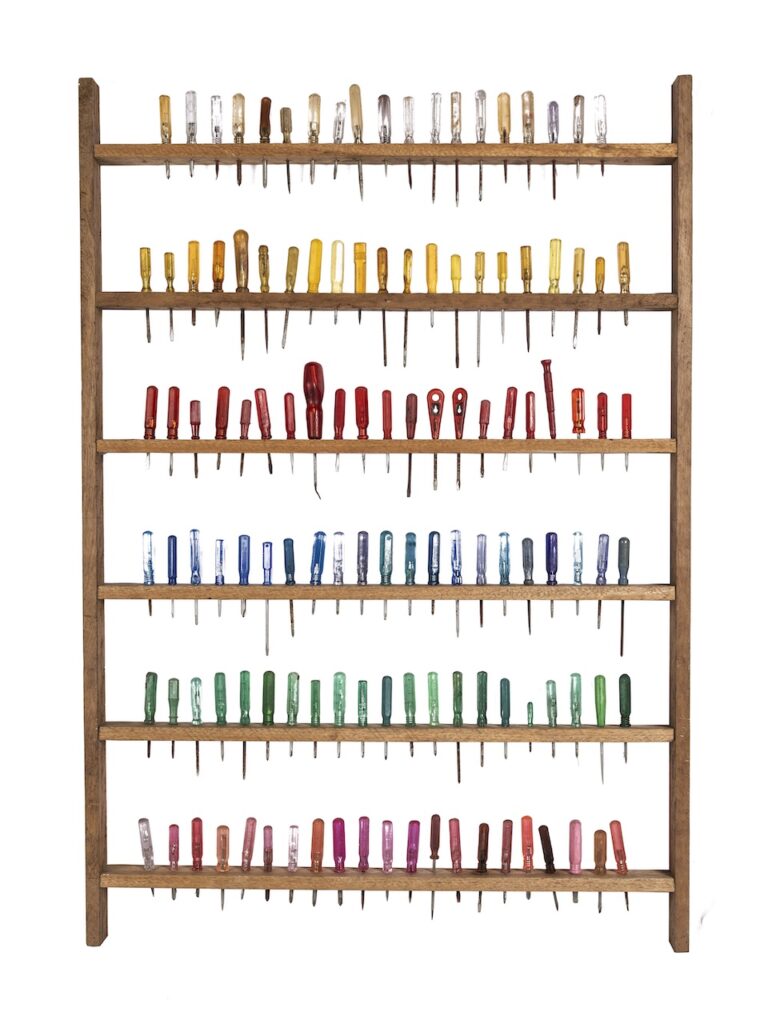

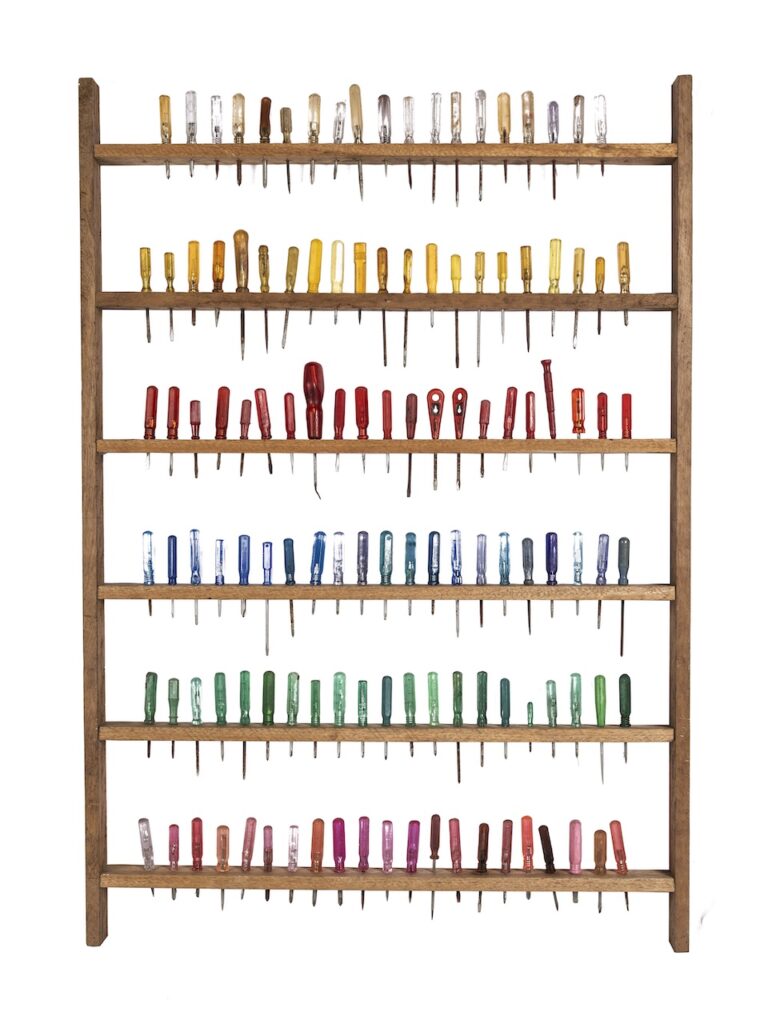

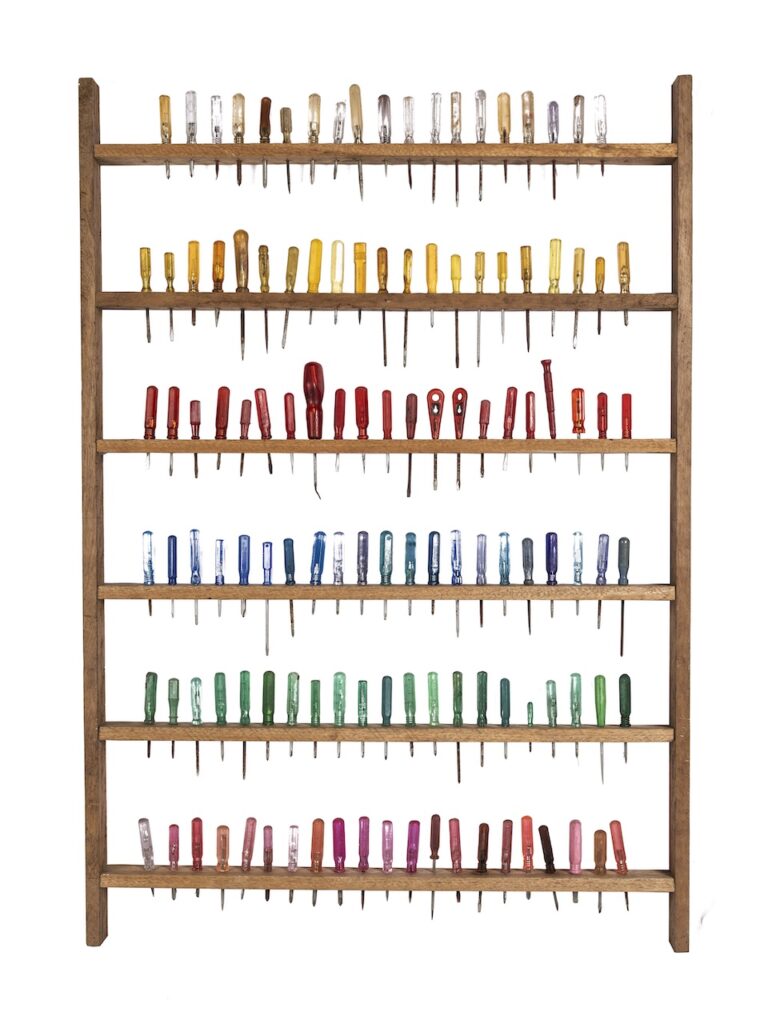

Rather than using a heavy hand on her materials, Christina “Ling” Quisumbing tackles each object with restraint and care. Often working with scraps of wood and discarded items—whether found or given—these materials are not transformed beyond recognition, but gently reassembled into something that reflects different chapters of her journey.

“When things are damaged or worn out, I feel compelled to fix them or give them a fresh start,” she says, a sentiment that quietly reveals much of her practice.

This impulse is less about returning objects to their previous state and more about gaining insight and clarity. Quisumbing has long been drawn to objects that exist in a state of in-between—“functional things that don’t function,” such as chairs you can’t quite sit on. In their brokenness, she finds an opportunity to tell a story: bits of dialogue, memories, and the beauty of imperfection, embracing the idea of letting the story unfold naturally.

Each component in Quisumbing’s assemblage is treated with unhurried patience. Time is spent sanding, distressing, cleaning, or revitalizing materials—not to erase their past, but to honor it. This slow, almost devotional process mirrors how she speaks about the objects themselves.

“Broken things have their own stories to tell,” she reflects, a philosophy that resonates across the exhibition. In Through Visual Poetries, the works feel less like statements and more like conversations.

Before assemblage became central to her practice, Ling had envisioned a different artistic path. As a student at the University of the Philippines’ College of Fine Arts, her training leaned toward editorial design, and she initially imagined herself becoming a children’s book illustrator. That trajectory shifted in the 1980s, when she moved to New York City to pursue a Master’s Degree in Studio Arts and Art Education.

“I finally gave in,” Ling recalls. “My earlier works were mostly paintings, figurative or representational.”

New York at the time was a city charged with creative energy. Widely regarded as the epicenter of contemporary art, it offered constant exposure to new ideas, practices, and communities. “I was exposed to a lot of art,” she shares. After completing her degree, Ling worked at a bronze foundry before taking on a full-time role as a page supervisor at the Frick Art Reference Library. She supplemented this with part-time work in galleries and art supply stores, carving out time for her own practice on weekends.

Building and sustaining an artistic career in New York was challenging. “The process is much more structured and formal,” Ling explains. “You need to submit a catalog of works and apply to be part of a show. You also have to think about studio rent, and working hours are not as flexible.” Even with these challenges, she showcased her work often, especially in alternative art spaces that encouraged experimentation and conversation.

Related story: The art of printmaking and letting the wood surprise you

Related story: Arts Month A-List: Concerts, exhibits, and art events to catch in Metro Manila

Related story: ‘A Symphony of Corals’ teaches the art of staying calm in a sea of chaos

Beyond the studio, New York became a site of political awakening. The 1980s marked the height of queer activism, and Ling became part of a group of artists, writers, and cultural workers who shared a similar creative and political beliefs. “By the mid-80s and late 90s, I was out and proud,” she says.

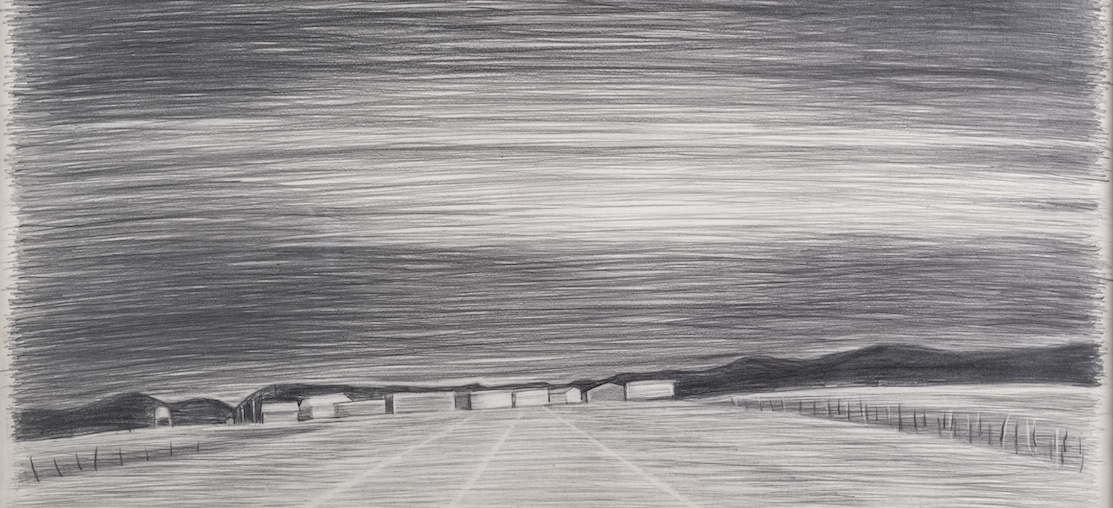

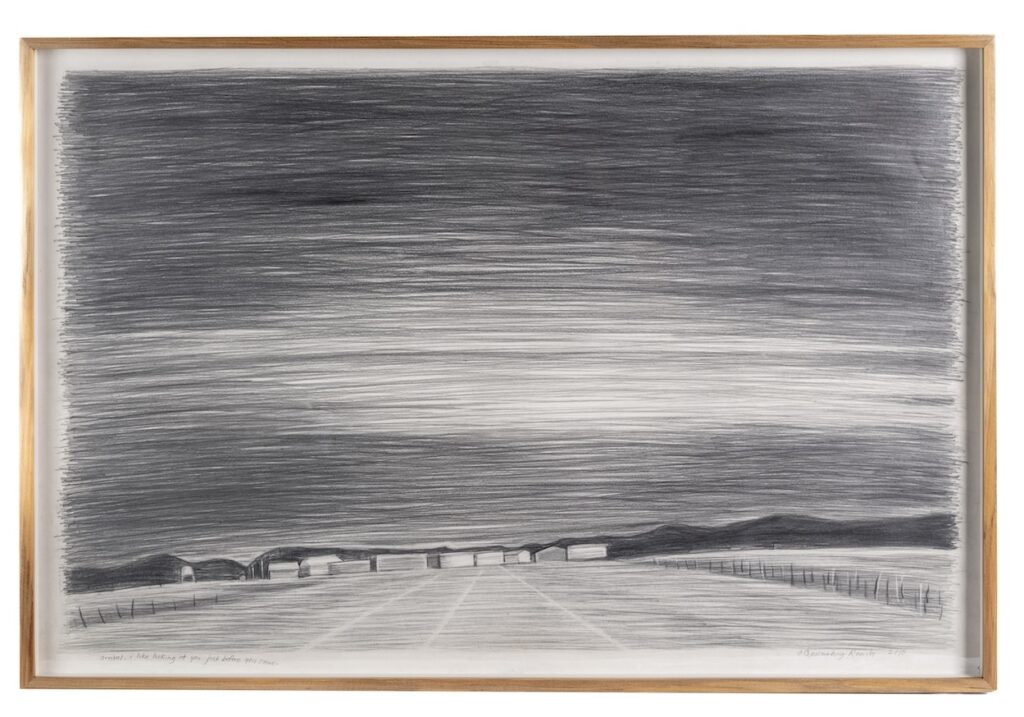

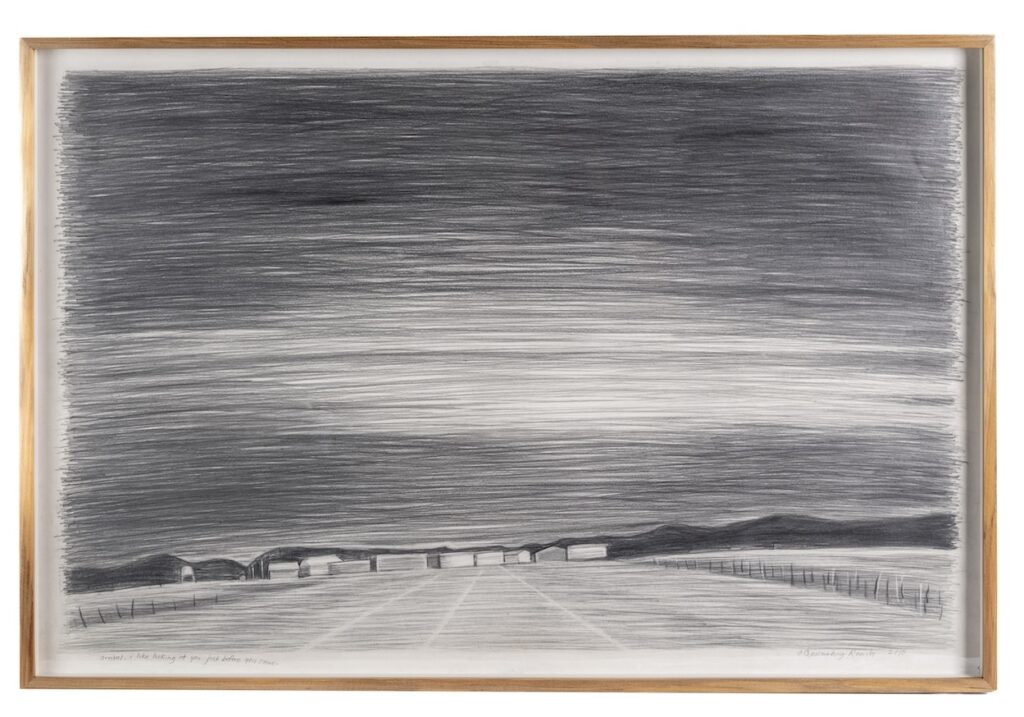

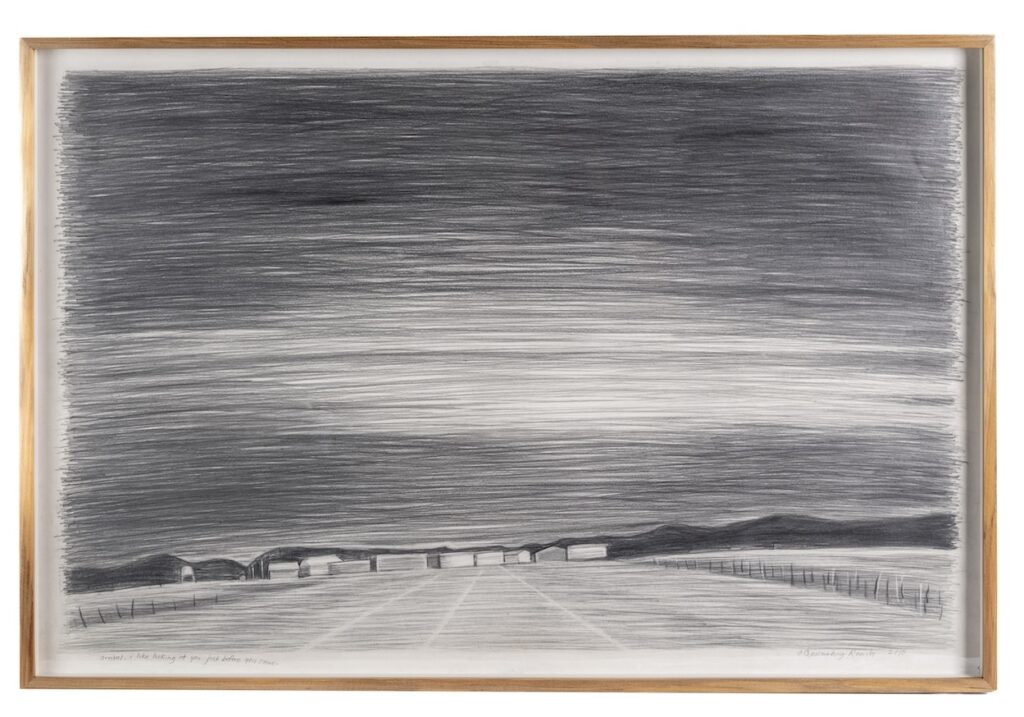

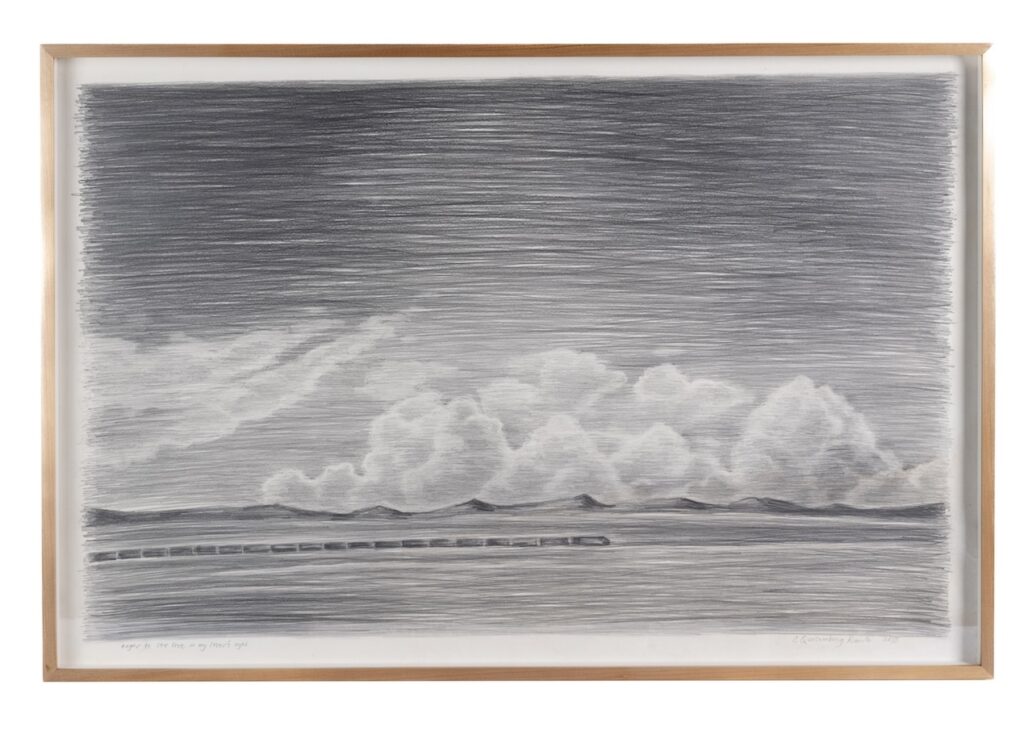

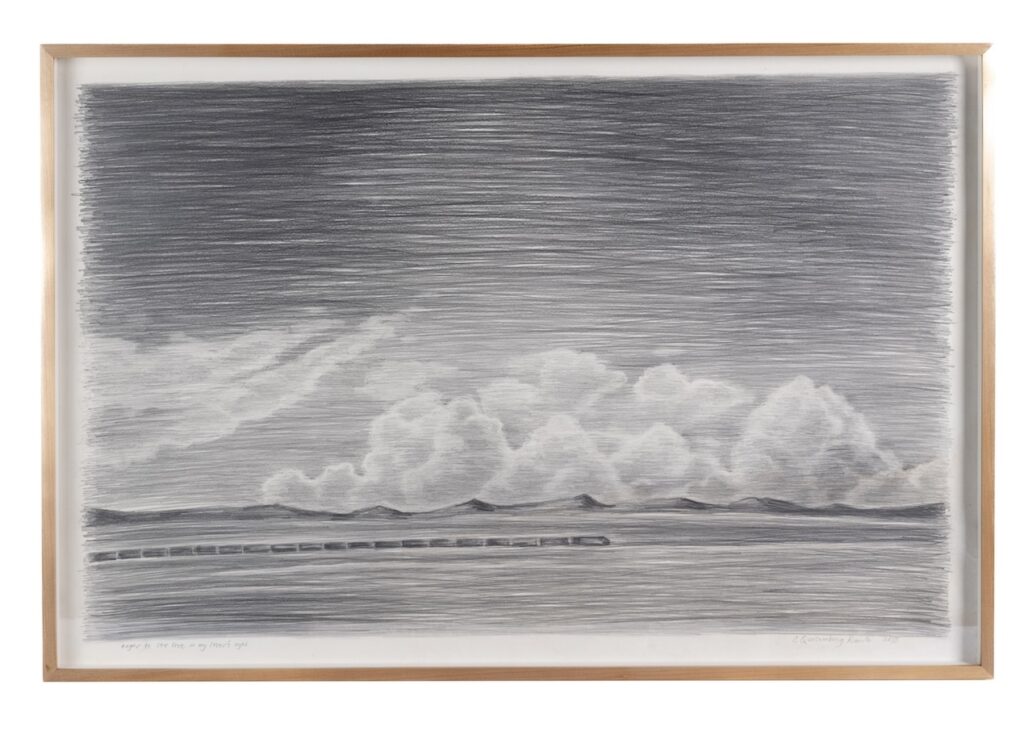

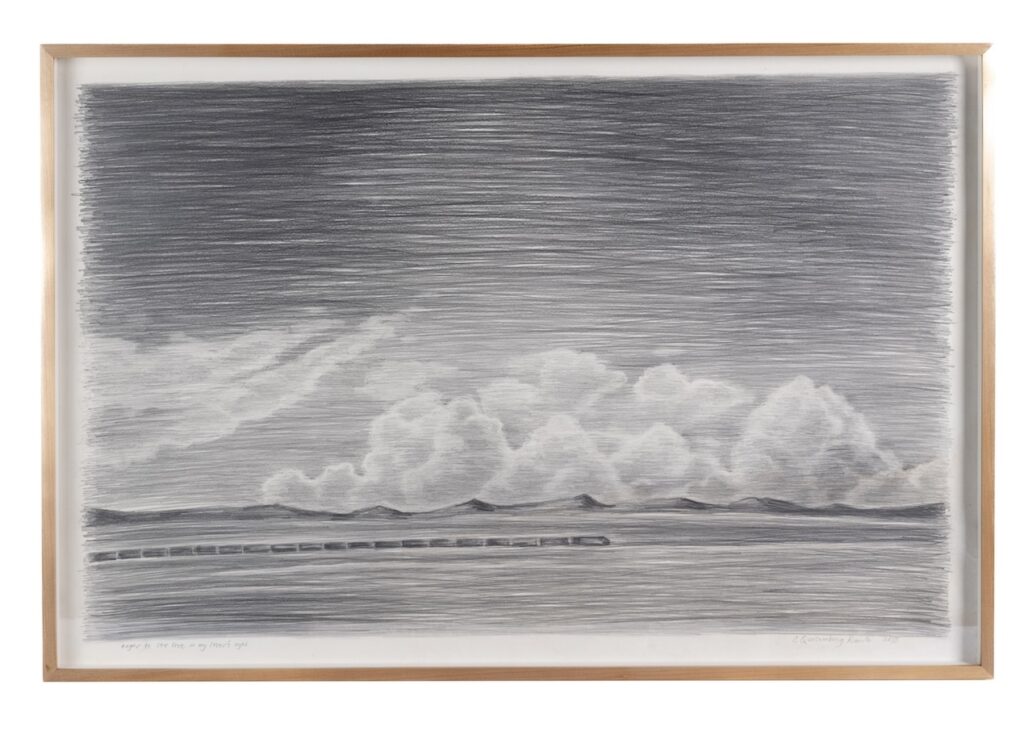

Ling often describes her art as a form of autobiography, capturing her experiences rather than showing them directly. Her series “Roadtrip” includes drawings from a two-month trip across the U.S. with her ex-girlfriend. Instead of well-known places, the drawings highlight brief moments they encountered. “They capture moments on the road versus landmark scenes,” she explains. “These scenes could be anywhere, not necessarily in the U.S.”

Now based in Manila as a full-time artist, Ling continues to build a practice built by patience, care, and collaboration. She goes beyond just creating art to mentor others. “It took me years to figure out a lot of things,” she shares. “If I can help someone, I take the time to guide them.” Recognizing the support she’s received, Ling sees mentorship as a way to give back. This approach is clear in the exhibition “LAKBAY 2026: Through Visual Poetries,” curated by Marika Constantino. Here, Ling is not only featured as an artist, but as a quiet influence, shaping conversations and inspiring new perspectives.

Ling’s art has a feeling of being caught between places. She carefully chooses her titles, showcasing her love for wordplay, using clever titles with ambiguity and irony. Rather than demanding interpretation, Through Visual Poetries invites viewers to slow down and listen. These works don’t solve the complexities of identity or healing; instead, they embrace them. It’s not about by focusing on what is worn, broken, or overlooked; it’s about recognizing something familiar—a reflection of stories that are shared, stitched together, and gently held.

Related story: New venue, new art, always captivating: What to expect at Art Fair Philippines 2026

Related story: Nine galleries unveil largest edition of ALT ART

Related story: 2025 in theater: How Filipinos deepened their love affair with musicals