Printmaking gives more people access to acquire art, expands who gets to exhibit, and where art can live.

I decided to set the tone for this year the way I’ve been craving to live more of my days lately: by showing up as a learner again.

I enrolled in a Woodcut Printmaking Workshop on December 6, 2025, with renowned artist Ambie Abaño, held as a whole-day session at the Philippine Women’s University’s Manuel Antonio Rodriguez Sr. (MARS) Center under the Artistic Research Center (ARC) program.

It was also the first external printmaking workshop organized through ARC. I came in excited and, if I’m being honest, anxious. I kept thinking: Will I finish something? Will I even enjoy this?

Ambie opened with a lecture that instantly grounded me. She started with what most people are familiar with: silkscreen printing, which allows you to produce an image uniformly several times because it uses a matrix. From there, she clarified something that stayed with me all day: printing is the act of transferring something from one surface to another. Printmaking, however, is when you transfer images for the purpose of creating an expression.

There’s printing, the process of transferring. And then there’s the hard part: creating the design on a surface that’s permanent. Woodblock printmaking began in China, first through seals and stone rubbings, and was later refined for paper during the Tang Dynasty. From there, it traveled across East Asia and eventually to Europe, becoming one of the earliest ways religious images were realized and shared with many.

In printmaking you apply pressure and the print becomes the final reveal on paper. And there’s always an element of surprise. With wood, for example, if it gets too hot, the wood contracts. The material develops ridges and grooves.

Democratizing art

Ambie dropped a line that made me smile so hard I wanted to write it down immediately: “Printmaking democratized art.”

I loved that. Because it’s true. In many media, art becomes something only the rich can access. Ambie gave an example: an original by National Artist BenCab can cost around P4 million, but a printmaking piece of the same frame size might be around P40,000.

That quote brought me back to my first purchased artwork on August 23, 2023 at the Modern and Contemporary Art Festival (MOCAF) in Raffles Makati. I bought a 9×12-inch rubber cut with chine collé of a bird in black and purple by my dear friend Melai Arguzon, the same friend who would nudge me into this workshop.

I wanted to support her and the price was reasonable—but I also wanted to experience how it feels to buy art. Weeks later, the Certificate of Authenticity arrived, and the artwork was delivered to my home wrapped in brown paper like a gift. A gift to myself.

Related story: Arts Month A-List: Concerts, exhibits, and art events to catch in Metro Manila

Related story: ‘A Symphony of Corals’ teaches the art of staying calm in a sea of chaos

The workshop

My tablemates were a lovely mix of people: a chef potter, an art graduate student, a doctor, a businesswoman, and an art teacher.

The first step was deciding what to draw, remembering that what you draw becomes the negative and inverse. In printing, the white space and the black space reverse. I asked myself: what’s easy and less curvy, but not boring and too linear?

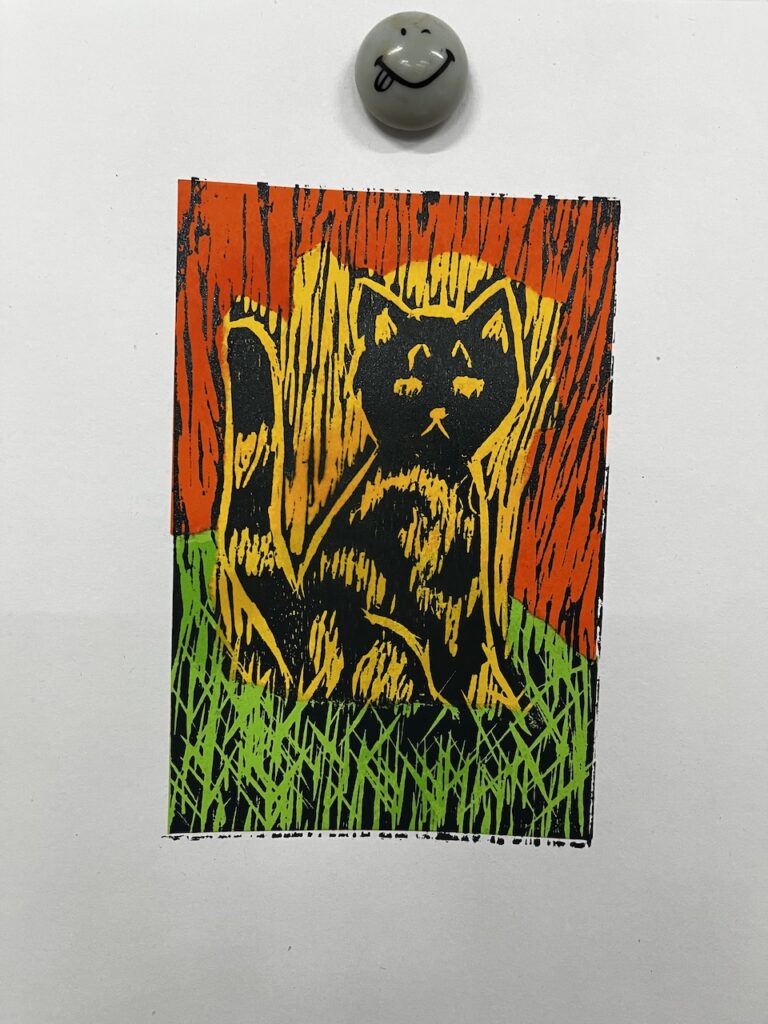

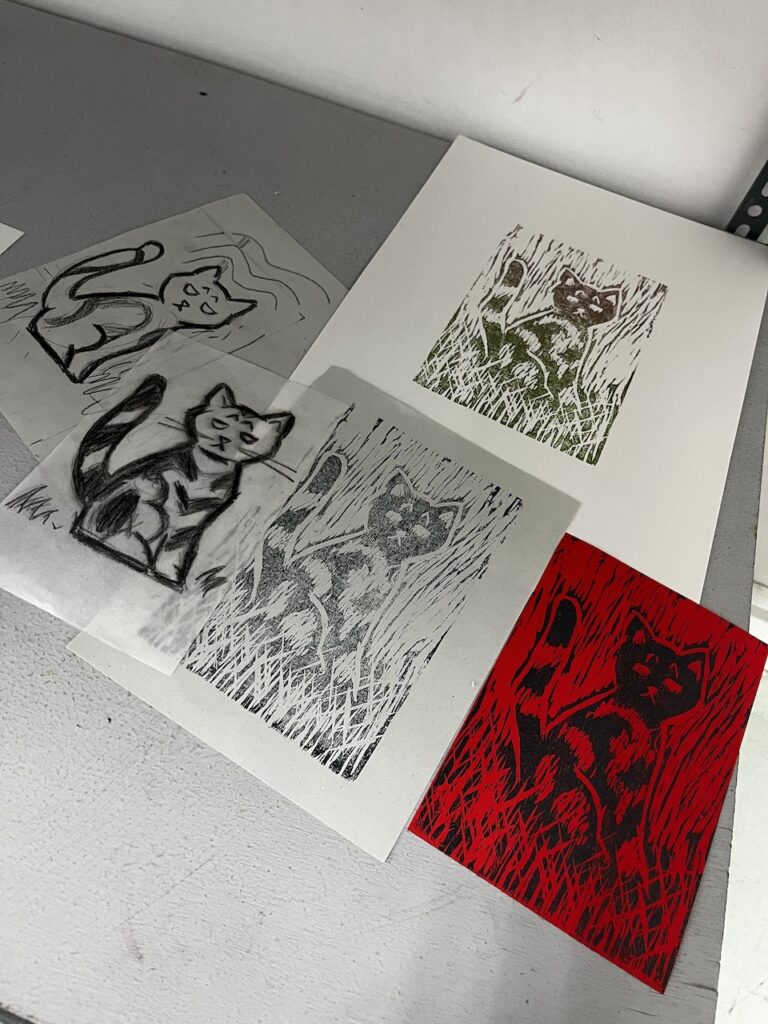

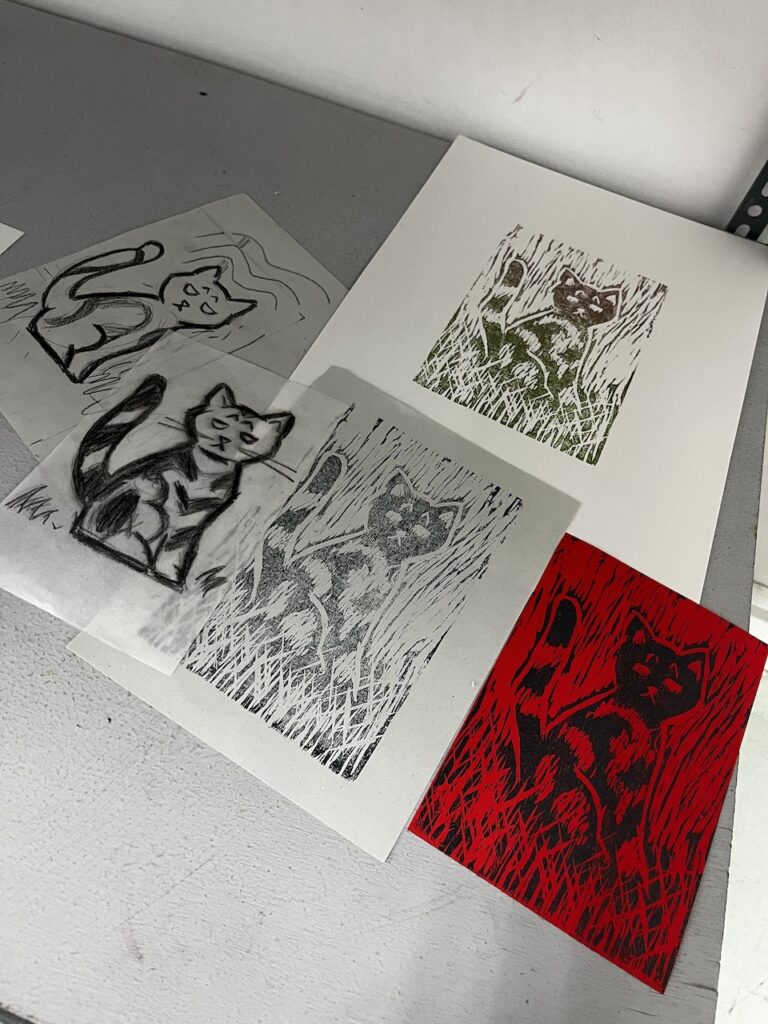

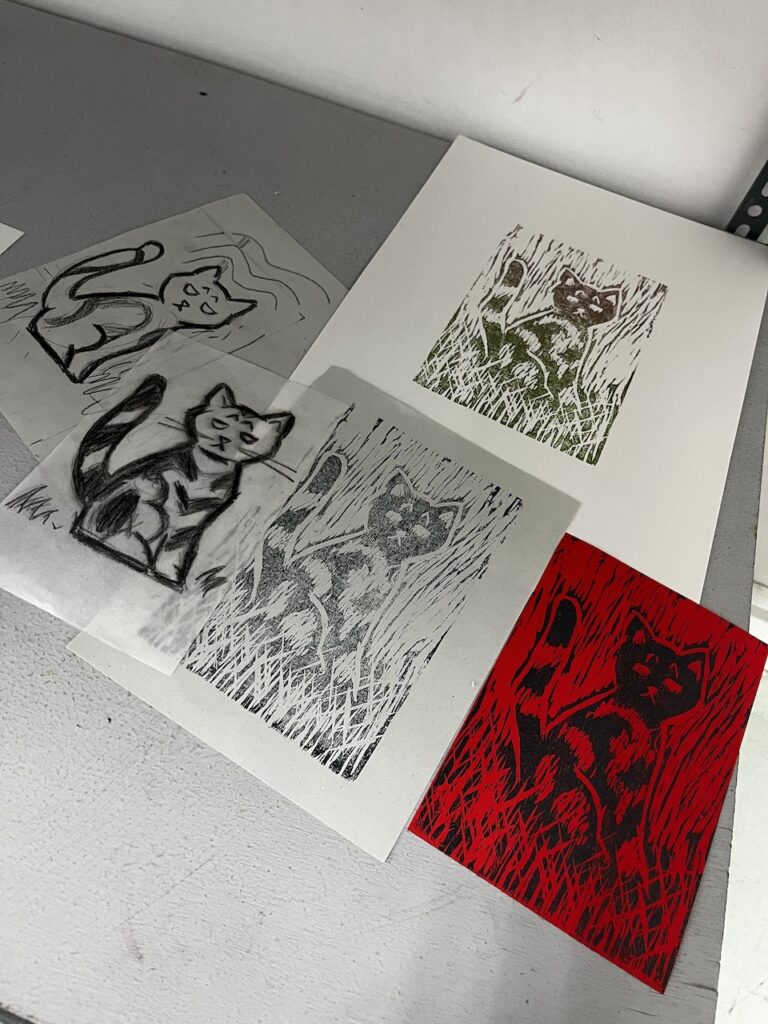

And then I knew. I chose my recently deceased cat, Noche. I drew him and imagined him in the garden, with grass made of straight cuts that flicked at the end, a contrast to the curves of his form. We sketched on pre-cut greaseproof paper, using a black 7B Mars Staedtler Lumograph pencil and really darkening the lines, then transferred the drawing onto a woodblock by rubbing the back of the paper to release the graphite.

The best tool for transferring, basically through burnishing, was a kitchen wooden spatula or serving spoon—a detail that perfectly aligned with the whole “democratizing art” idea. I laughed to myself, but really, it was ergonomic, lightweight, and solid enough to rub the graphite onto the wood.

Ambie sauntered over to our table. She noticed I was holding the U-cutter awkwardly, and that I was pinning the woodblock down with my index finger and thumb while sitting on the stool.

She said, “Oh, I want you leaving as a whole person,” and I thought she was being philosophical. Then she demonstrated a better way. She pointed out that my body was adjusting to the woodblock, when the truth is, I can always flip it, turn it, place it wherever it works best on the table. She showed me rubberized anti-slip mats so I wouldn’t need to press too hard just to keep the woodblock from sliding on the glass worktable.

I heeded her advice. I flipped the woodblock, turned it to the side. My shoulders relaxed. I didn’t need to stand up. And I imagined how, with the way I was doing it earlier, I could have actually cut myself.

The wood had ridges and “moles” I couldn’t carve out. Ambie told me to leave them. Think of them as beauty marks no other print can have.

Then she turned her attention to my seatmate, the art grad student, Audrey. Audrey made a really intricate flower. She came prepared with her own cutting tools and cleaning materials: lotion and baby oil. She was Ambie’s student from UP Diliman Fine Arts.

And yet she seemed even more anxious. Ambie told her to let go of perfection. She’s doing enough. Enjoy. Audrey smiled, but I could feel it: that youthful, defiant energy, never quite satisfied with what she’d done.

The workshop moved fast. The vibe was learners one and all. It was fascinating watching how the Materica Gesso paper, the final print’s home, was meant to “fall” onto the inked woodblock, gently. You set it up with taped guides, a non-slip mat, and careful alignment, then let the paper drop onto the block. After that, you rub it down firmly with a kitchen wooden spatula, peel it off slowly, and hang it to dry.

By 3 pm, Ambie introduced chine collé: colored paper cut or pasted together, then printed on, adding dimension to the final artwork. Blue, orange, and green were suggested, but I opted for orange, green, and yellow.

It looked Rastafarian, but I wanted Noche’s chine collé to be melancholic without being too gloomy, like a garden sunset. I was still sad that he died. But I wanted to remember him where he was happiest: in the garden.

As 5 pm approached, we collectively clamored for a part two. Hopefully, PWU’s Artistic Research Center brings Ambie back for another workshop.

Even as the day rushed toward its ending, Ambie didn’t skip teaching us how to clean the tools and the work area. My blackened fingertips were clean in no time, and of course, I still washed my hands with dishwashing soap.

I remembered my earlier grip on the cutter, and Ambie’s line: I want you leaving as a whole person.

And somewhere between the wood’s ridges, Audrey’s perfectionism, and the kitchen spatula masquerading as an art tool, I rediscovered something personal: I’ve always liked making things. It doesn’t have to be genius or avant-garde enough to sell at auctions or exhibits. It can be for pure pleasure.

Maybe that’s how I want to set the tone for the year: not with a grand reinvention, but with a small, steady practice of relinquishing control. After all, one must relinquish absolute control and accept the surprises, like the grooves, moles, and warps of a woodblock.

Related story: New venue, new art, always captivating: What to expect at Art Fair Philippines 2026

Related story: Nine galleries unveil largest edition of ALT ART