James Cameron’s newest Avatar movie arrives not as a simple sequel but as a thesis statement for why this saga is still burning and refuses to cool down.

If Avatar was about awe and invasion, and The Way of Water about grief, kinship, and survival, Fire and Ash—even in concept—signals confrontation. Not just between humans and Na’vi, but within Pandora itself. This is Cameron turning the elemental dial toward volatility, moral ambiguity, and the uncomfortable truth that no culture, however sacred, is immune to darkness.

A shift in element, a shift in tone

The most immediate promise of Fire and Ash is tonal. Water brought fluidity, healing, and mourning. Fire brings rupture. It consumes, transforms, and leaves scars that do not easily fade. Cameron has always used environment as philosophy, and here fire feels less like spectacle and more like indictment—of colonial greed, of righteous violence, and of the myth that harmony is universal or effortless.

Pandora, once framed as a largely unified ecological and spiritual counterpoint to Earth’s corruption, now appears more fractured. The introduction of Na’vi clans aligned with fire and ash reframes the series’ moral geometry. This is not a binary of noble indigenous people versus destructive outsiders. It is a world with internal hierarchies, grudges, and the capacity for cruelty. That alone makes Fire and Ash feel like the most dramatically ambitious entry yet.

Jake Sully and the cost of permanence

Jake Sully’s arc has always been about permanence—choosing a life, a people, a planet, and paying the price for that choice. By the time of Fire and Ash, Jake is no longer the audience surrogate discovering Pandora. He is a relic of an earlier war, a leader shaped by loss, and a father whose decisions ripple outward with devastating consequence.

What Fire and Ash seems poised to interrogate is whether Jake’s brand of leadership—protective, militant, uncompromising—has begun to mirror the very forces he once fought. Fire is not only external here; it burns in Jake’s instincts. Cameron has never been subtle, but he is precise. If Jake becomes more rigid, more willing to justify violence in the name of survival, the film’s emotional conflict may be its most unsettling yet.

Related story: REVIEW: ‘Zootopia 2’ is a bigger story and a better look at its characters

Related story: REVIEW: Why ‘Wicked: For Good’ is better than its predecessor

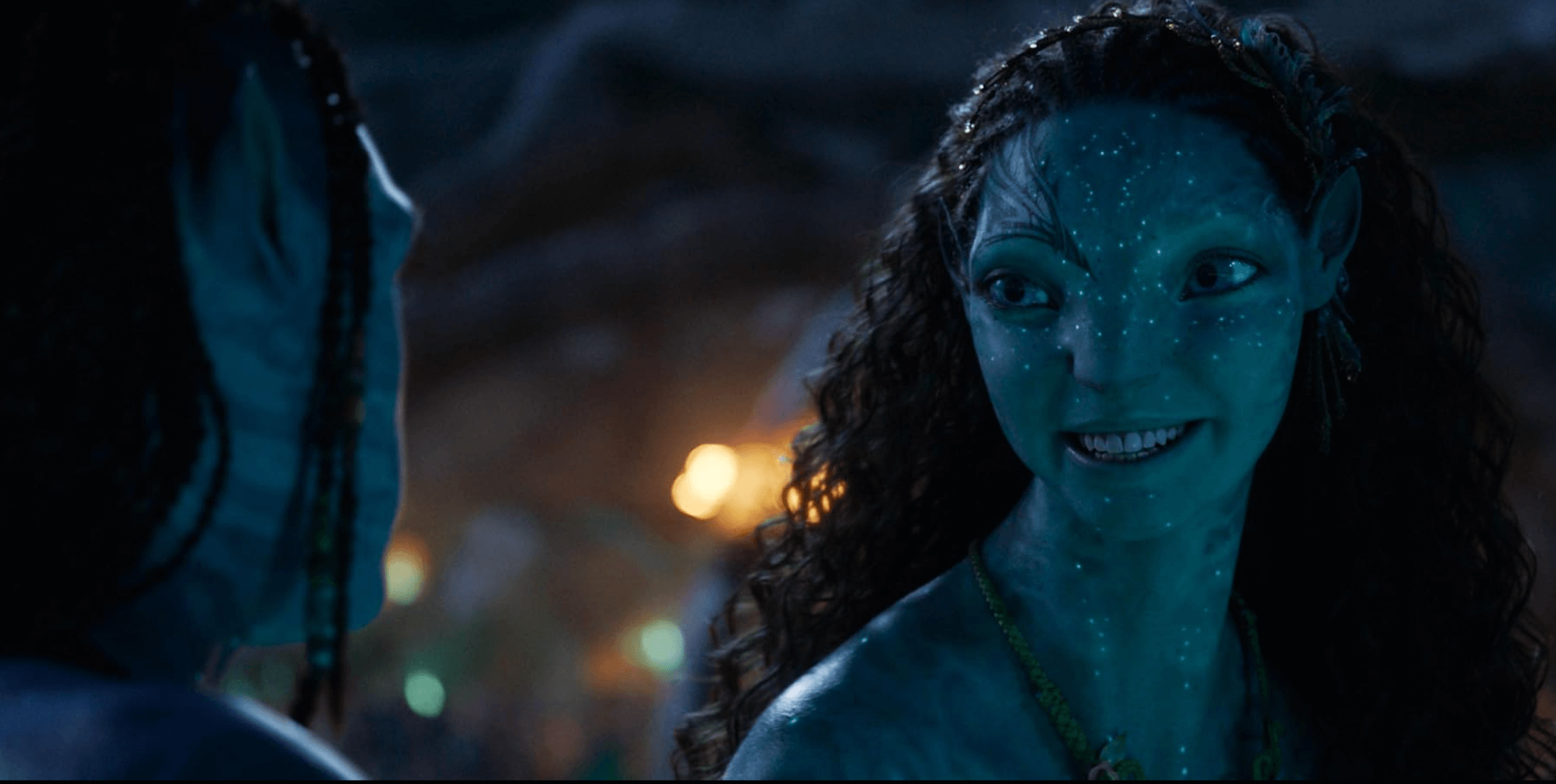

Neytiri: Rage as inheritance

If Jake represents the burden of leadership, Neytiri embodies inherited rage. Her grief across the series has never been allowed to fully resolve, and Fire and Ash seems ready to stop asking her to soften it. Fire is her element—fury born of repeated loss, of a world continually threatened, of sacred ground turned to cinders.

What makes Neytiri compelling is that her anger is never abstract. It is personal, ancestral, and justified. But Fire and Ash appears less interested in validating that anger than in exploring what happens when it becomes doctrine. At what point does righteous fury calcify into something indistinguishable from hatred? Cameron’s willingness to let a heroic figure sit inside that discomfort may be one of the film’s greatest strengths.

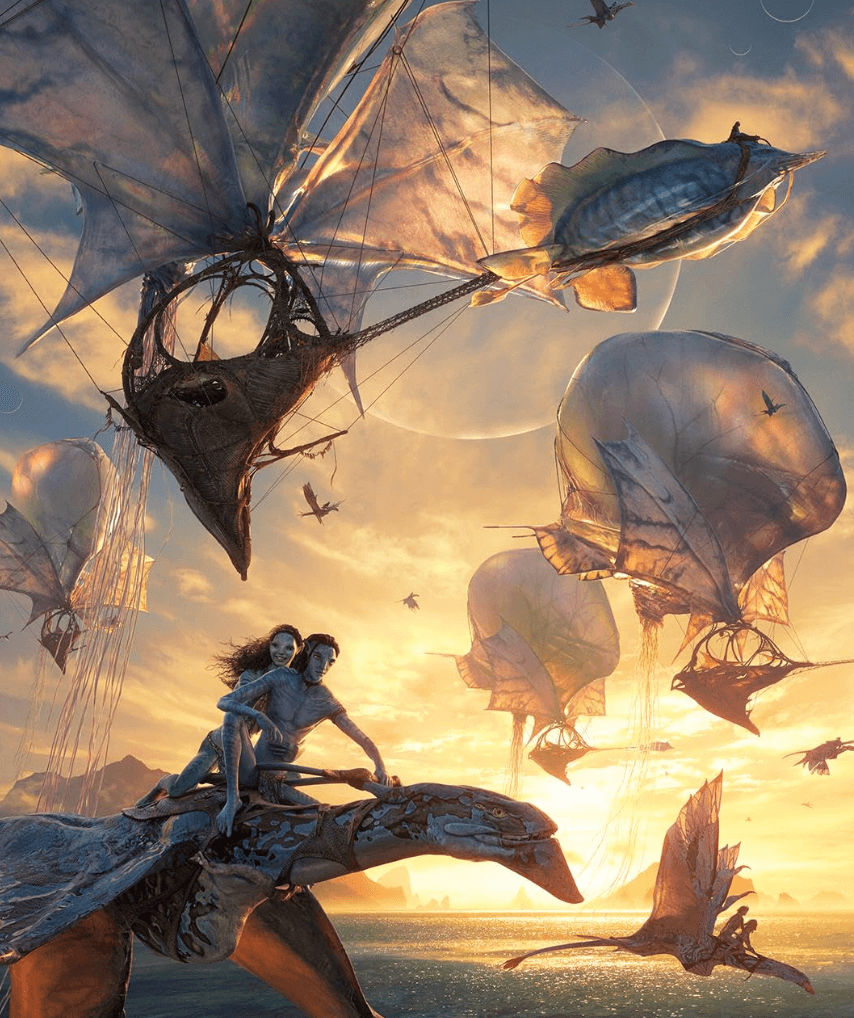

Visually, Fire and Ash promises a Pandora we have not seen: scarred landscapes, volcanic terrain, ecosystems shaped by destruction rather than abundance. This matters because Avatar has always risked romanticizing nature as endlessly resilient. Fire disrupts that fantasy. Ash lingers. Forests do not simply bounce back.

By showing a Pandora that can be wounded beyond easy repair, Cameron sharpens the franchise’s environmental politics. This is no longer a parable about saving a pristine Eden. It is about triage. About deciding what can be preserved, what will be lost, and who gets to make those choices.

Humanity as a persistent, petty force

The human presence in Fire and Ash—corporate, militarized, extractive—no longer needs introduction. What will be interesting is how diminished yet dangerous it has become. Humanity in Avatar is not evil because it is powerful; it is dangerous because it is desperate. Fire, after all, is humanity’s oldest tool. That symbolic overlap feels intentional.

Rather than escalating spectacle for its own sake, Fire and Ash appears to reframe human antagonism as corrosive rather than dominant. Like embers that reignite conflict long after the main blaze is gone, humanity’s influence persists in subtler, more destabilizing ways.

The greatest risk Fire and Ash takes is refusing comfort. Audiences accustomed to clear heroes and villains may bristle at Na’vi who are not gentle, at resistance movements that harm innocents, or at protagonists who make unforgivable choices. But this is also the franchise growing up.

Cameron has spent decades perfecting technological wonder. Here, the real advancement may be ethical. Fire and Ash seems intent on arguing that survival does not automatically confer virtue, and that cultural sanctity does not preclude brutality. In doing so, it edges closer to tragedy than triumph.

A saga still justifying its scale

Critics often ask whether Avatar earns its runtime, its budgets, its insistence on being event cinema. Fire and Ash, at least in ambition, answers yes—not because it is bigger, but because it is harder. Harder emotionally, harder morally, harder to resolve.

If Avatar began as a story about seeing the world through another’s eyes, Fire and Ash is about what happens after empathy fails—after understanding does not prevent violence, and love does not guarantee peace.

Avatar: Fire and Ash feels less like a chapter and more like a reckoning. A film about what remains when harmony collapses, when myths burn away, and when survival demands choices that leave no one innocent.

If Cameron delivers on the promise embedded in the title, this may be the Avatar film that lingers longest—not because of its visuals, but because of the ash it leaves behind.

Related story: Golden Globes 2026 nominees point to a competitive awards season ahead