The collaboration is a masterful display of selective weaving—a little Peruvian here, a touch of Japanese there, with Filipino and Spanish threads seamlessly stitched in.

Looking at one plate during the collaboration lunch by chefs Chele Gonzalez and Santiago Fernandez, you’re not quite sure if you’re staring at a rock or something you’re supposed to eat. It has the jagged texture of a rock shaped by relentless ocean waves with moss clinging insistently. But it’s not a rock—it’s clay, salted and cut in the middle, to cook the sweet potato inside.

Some things are not what they seem at this nine-course tasting lunch at Gallery by Chele. And that’s the point: appearances are meant to mislead the eyes, only for the first bite to bring you back to where the dish truly belongs.

At the second of two events, the guests are mostly independent chefs and restaurateurs who are shaping Manila’s dining scene plate by plate. If you locked them all in this room, the well-heeled in Manila would not have a place to go for dinner that night. But for lunch, we are all experiencing what free thinking in food tastes like.

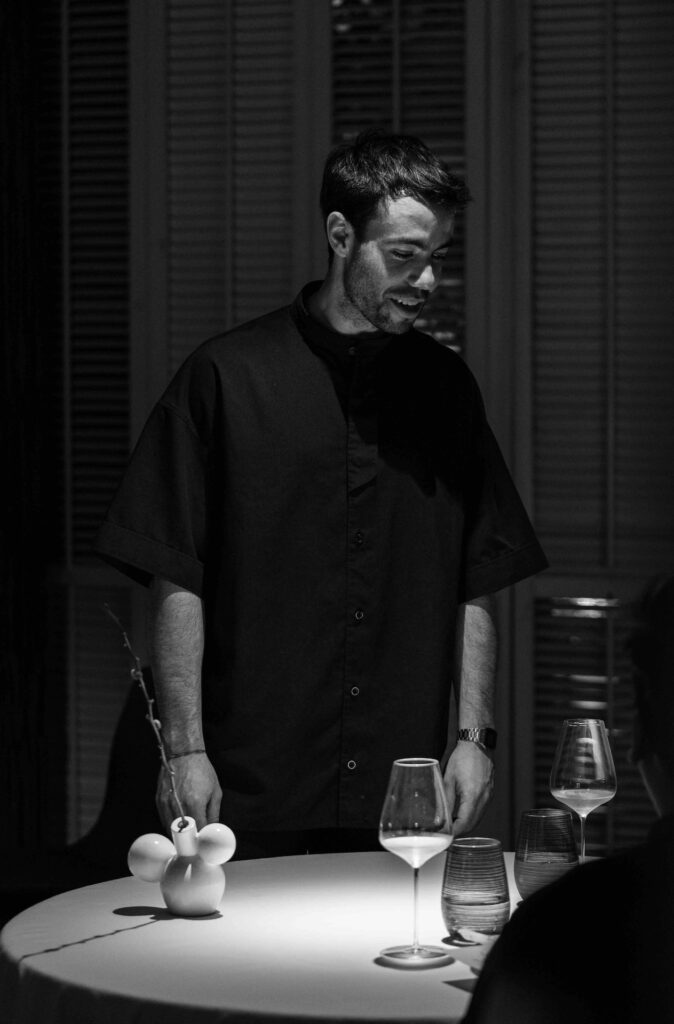

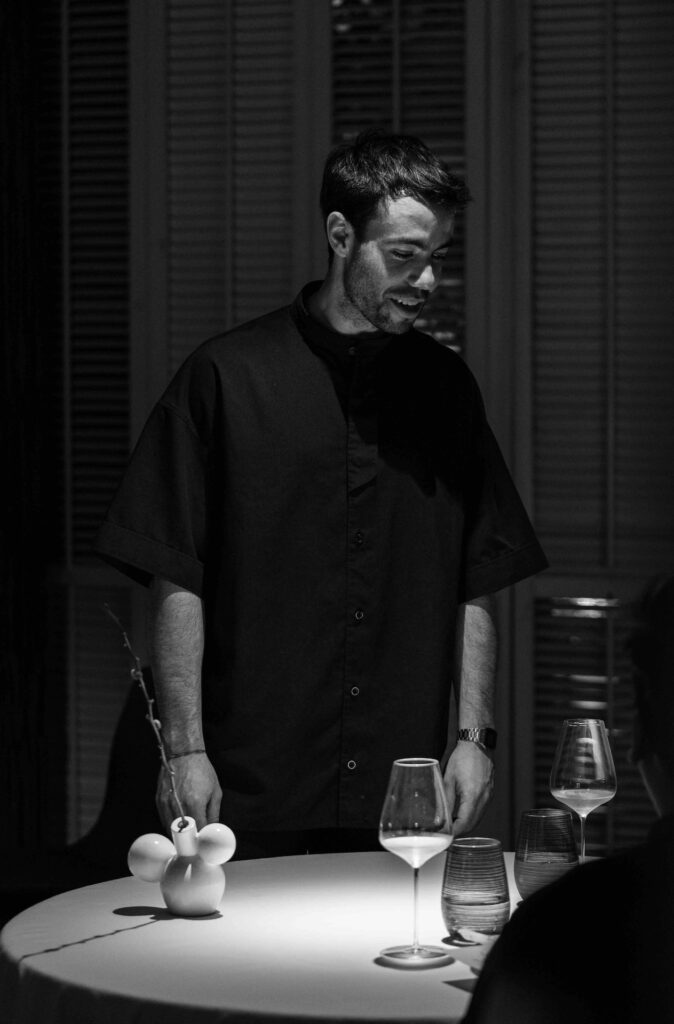

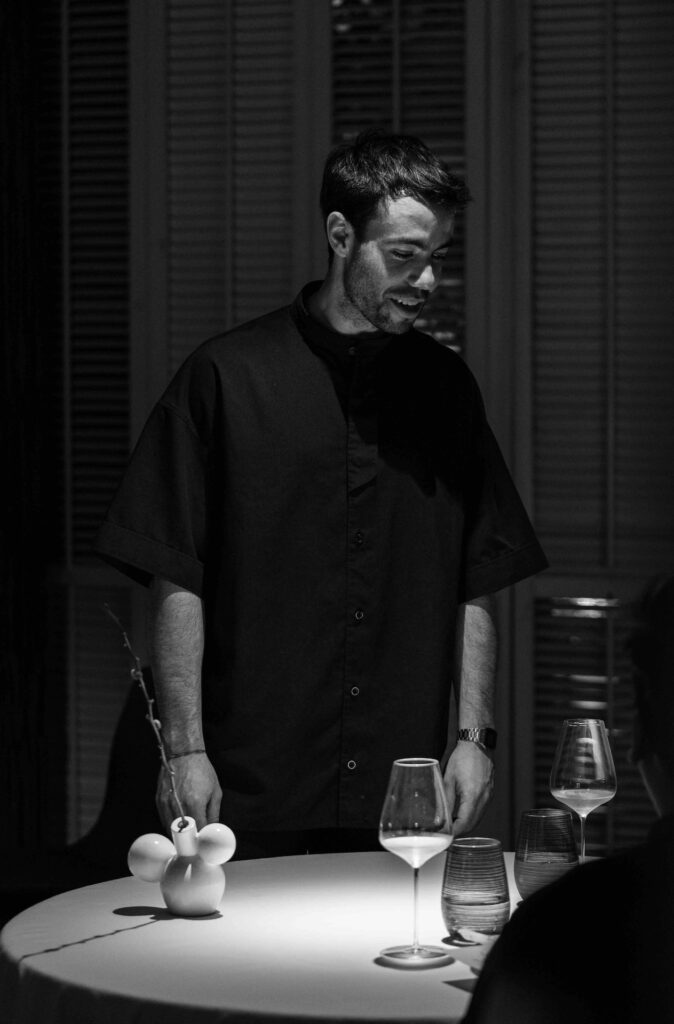

This is the first of the Edible Thesis Series: Free Thinkers, where Chele Gonzalez invites chefs from around the world for limited events.

And so here we are with Santiago Fernandez, the Michelin-starred head chef of Tokyo’s MAZ restaurant. Fernandez was born in Venezuela and raised in Peru, one of the world’s most biodiverse countries, where the plate mirrors the landscapes—from the Pacific Coast teeming with fish to the Andes’ thousands of potato varieties, and the Amazon’s wealth of fruits, herbs, and river fish. Each of these ecosystems offers an abundance of flavor, shaping a philosophy that’s “part of a larger story of land, memory, and identity.”

This rock-like mold isn’t just for visual effect, but serves as a substitute for the Peruvian tradition called huatia or a traditional “earth oven,” where large stones are heated in a fire and then placed in a pit. Potatoes, tubers and meats are then layered between the hot rocks and covered with banana leaves and earth to trap the heat.

With our humble kamote, you begin to understand what Chele Gonzalez is trying to do with this series: to expand the inventiveness of his restaurant’s laboratory to another level.

The collaboration has both chefs making a deep dive into the landscapes and food of their beloved countries: Chele’s Spain and his adopted country the Philippines, and Fernandez’s Peru and Japan.

What, exactly, is a culinary “free thinker”?

I think that rather than rattling off adjectives, the best way to illustrate a culinary free thinker is to go by examples outside their world. We call Galileo a free thinker because he dared to insist that the earth revolved around the sun, not the other way around (the existence of flat-earthers after all the space exploration since the 1960s still boggles my mind!). Voltaire used wit and satire against kings and clergy. In literature, James Joyce broke open the form of the novel, while Virginia Woolf collapsed the wall between interior thought and narrative (yes, she gave a name to your stream of consciousness).

You get the point—these are people who broke away from tradition and institution to innovate, to rebel, and to translate thought, logic, and culture beyond the mainstream.

In cuisine, free thinkers are chefs who bring that same spirit of inquiry to the plate. No matter how you feel about molecular gastronomy, Ferran Adrià and his El Bulli restaurant transformed food into molecular theater and mentored a new generation of chefs who looked at ingredients and thought of a million other ways to cook them. Alice Waters of Chez Panisse insisted that a carrot could tell the story of a farm—and the hands that worked its soil. And René Redzepi of Noma turned foraging into the heartbeat of modern fine dining.

Santiago Fernández and Chele González belong to this fold. With their collaboration, free thinking in edible form brings landscapes and memories into their plates—and to our table.

Related story: Sober sophistication: Marina Wilkis elevates non-alcoholic pairings with coconut innovation

Related story: The subtle brilliance of Naoki Eguchi’s omakase

Where mountains meet seas

At the crossroads of Peru and the Philippines is ceviche or kinilaw. I love this dish not only for its freshness but because, like uni, you can eat it in the most expensive restaurant—or buy it on a boat in the middle of the sea from a guy on a kayak, who hands you just-sliced fish or cracked open sea urchin marinated in his homemade vinegar for less than P100.

But not today. We have, after all, two free thinkers in the kitchen—and so ceviche isn’t just ceviche, at least not the Filipino kinilaw we know, and not even the Peruvian ceviche that Fernandez knows and loves.

Fernandez explains, “Ceviche is very interesting because it comes from the Incas. They used to do it not with citrus fruits but with a type of long passion fruit we call tumbos. This how they preserved the fish—in its juice. It was overcooked by the sourness, and then little by little, when the Japanese arrived in Peru, it became exactly the ceviche we know—raw seafood that we cook with citrus.”

Chele and Fernandez’s ceviche—with fish, scallops, nipa and nata de coco—hits that sweet spot between the Peruvian and Filipino tradition. “This was a completely collaborative dish where we improvised to find something in between, and finished with fermented coconut,” Fernandez says.

Colors of the earth

At MAZ in Tokyo, Fernández and his team are very intentional with their color palette on the plate. He brought this to Gallery by Chele, where we are presented with a Pantone strip of earth colors derived from actual Peruvian natural dyes, each hue representing an ingredient, such as different varieties of cacao, potato and corn.

The Pantone strip introduces us to a dish of tubers because, well, Peru is considered the birthplace of the potato with over 3,000 varieties ranging from tiny ones to large, starchy types. The bowl becomes a shallow vase filled with sculptural curls that call to mind the resilience of root vegetables transformed into something light and almost floral.

It’s a meditation on tubers, if you will, the kamote that most Filipinos take for granted because it’s everywhere—deep-fried with brown sugar on the streets, steamed, boiled and rolled in white sugar in some regions, added with sour ingredients in others.

Masterful dishes

The two chefs’ collaboration is a masterful display of selective weaving—a little Japanese here, a touch of Peruvian there, with Filipino and Spanish threads seamlessly stitched in.

While Fernandez’s MAZ in Tokyo (#43 in Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants) is a fine-dining South American restaurant, Japanese cuisine and ingredients have inevitably found their way to his kitchen. Gallery by Chele (#72 in Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants), on the other hand, is Chele’s love letter to the Philippine archipelago, which he has visited from top to bottom in the years he has lived here.

One ingredient that Fernandez delighted in finding in Manila is palm heart or ubod, which is grown in and exported by Peru, but absent in Japan. He used this in the slipper lobster dish along with rocoto chili pepper, a hot, sweet pepper from the Andes mountains of South America.

Two dishes that strike me as quintessential culinary swaps are the Iberico Ramen and the Wagyu Kare-Kare. Each plate takes a familiar comfort food from one tradition and recasts it through another technique. The ramen noodles are made from cuttlefish and the pork is from Spain’s Iberian peninsula, while kare-kare is deconstructed and elevated using marbled wagyu. In two other dishes, the grouper comes with chorizo and yuzu; and the octopus with spirulina and tako liver.

The chefs also share a fascination for cacao and its by-products. Aptly called “A Thesis on Cacao Family,” the desserts feature cacao; the green macambo that’s native to the Amazon region between Peru and Colombia; and cupaucu or white cacao, which looks like the white meat of caimito.

Our lunch is the second of only two events that Chele and Fernández cooked together. Most of the tables are occupied by young chefs and restaurateurs in Chele’s circle, the kind of people shaping Manila’s dining scene plate by plate.

If you locked them all in this room, the well-heeled in Manila would not have a place to go for dinner that night. But for lunch, we are all experiencing what free thinking in food tastes like.

Gallery by Chele is located at the 5th floor of Clipp Center, 11th Avenue corner 39th St., Taguig. Call 09175461673 for reservations.

Related story: A tale of two stunning designs

Related story: Cantabria by Chele Gonzalez boasts new flavors—and a new Spanish chef