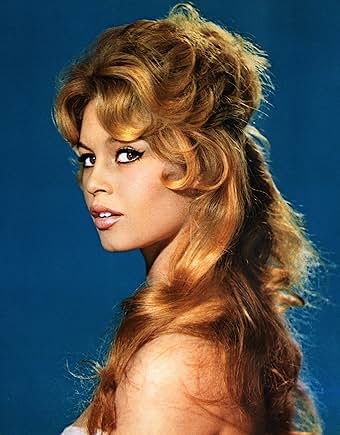

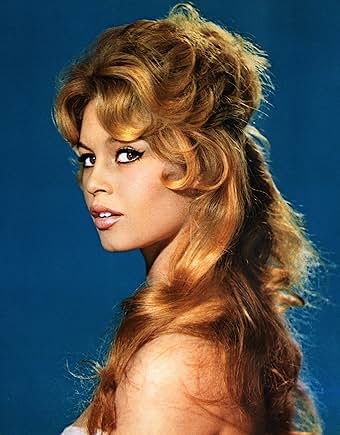

Bardot was the most desired woman on earth—and she was determined to disappear.

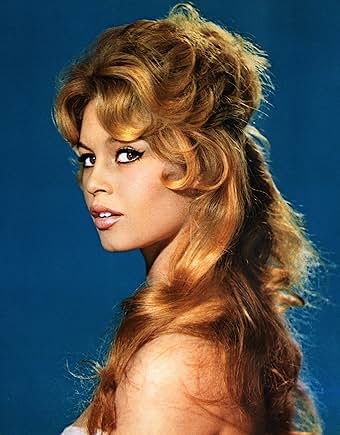

Brigitte Bardot did not merely become famous. She triggered a crisis—of morality, of masculinity, of modern spectatorship. She emerged at the exact historical moment when postwar Europe was loosening its grip on repression but had not yet learned how to live with freedom. What followed was not adoration but possession. Not liberation, but surveillance.

Her life is not the story of a star ascending and fading. It is the story of a woman who escaped—from cinema, from myth, from desire itself after discovering that fame was not a pedestal but a cage.

To understand Bardot is to understand the price women pay for embodying fantasies they did not consent to invent.

Brigitte Anne-Marie Bardot was born on September 28, 1934, in Paris, into a rigid, upper-middle-class family defined by discipline, silence, and propriety. Her parents, Louis and Anne-Marie Bardot, believed emotion was indulgence and obedience was love. Affection was scarce; praise was rarer.

France did not know what to do with her. The world could not look away. By the late 1950s, Brigitte Bardot was among the most famous women on earth.

Bardot later described her childhood as cold, punitive, and lonely. Ballet was introduced early, ostensibly to refine her posture and manners, but it quickly became an instrument of control. Ballet taught her discipline, endurance, and how to inhabit her body without speaking—a skill that would later become her most powerful cinematic weapon.

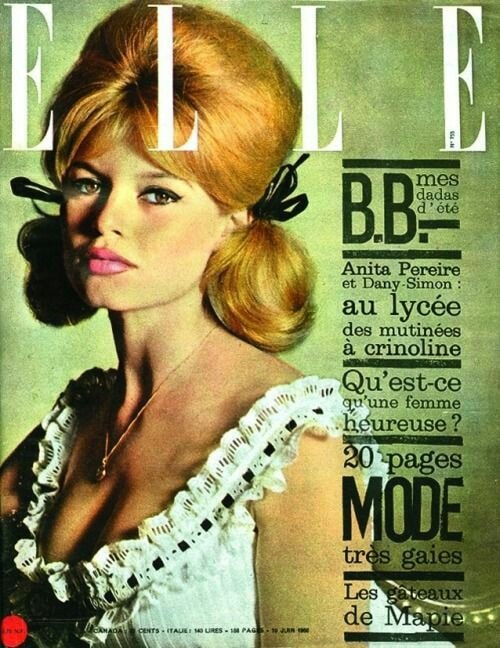

She was not encouraged to dream. She was expected to comply. By adolescence, however, Bardot’s beauty made compliance impossible. At fifteen, she appeared on the cover of Elle magazine. The image was not overtly sexual, but it radiated something dangerous to conservative postwar France: ease.

That cover changed everything.

Roger Vadim: Love, escape, and construction

To Roger Vadim—a writer and aspiring filmmaker nine years her senior—Bardot represented something new. Not glamour. Not polish, but freedom without explanation.

Bardot fell in love with Vadim because he offered escape. They married in 1952, when she was just eighteen. The union was as strategic as it was romantic. Vadim became her guide and protector.

He cast her in early film roles, encouraging her not to “act” but to exist. He understood that Bardot’s power lay in instinct. She did not project desire; she contained it, carelessly, which made it more potent.

Their collaboration culminated in 1956 with And God Created Woman (Et Dieu… créa la femme). The film was a scandal and a revelation. Bardot’s Juliette Hardy danced barefoot, loved freely, refused shame, and—most unforgivably—was not punished for it.

Audiences were outraged, critics were scandalized. Men were transfixed, women were unsettled. The film did not merely make Bardot famous. It recalibrated the male gaze. She did not perform sexuality for men; she existed within it, indifferent to their moral frameworks. France did not know what to do with her. The world could not look away.

By the late 1950s, Brigitte Bardot was among the most famous women on earth. She was also among the most hunted. Paparazzi followed her relentlessly, scaling walls, ambushing cars, invading bedrooms. Bardot’s body became public infrastructure. Her face was reproduced endlessly, stripped of context, desire projected onto it without limit.

She could not walk alone. She could not love privately. She could not disappear.

The marriage to Vadim collapsed under the weight of her fame and her growing independence. Bardot fell in love with Jean-Louis Trintignant, her co-star in And God Created Woman. Their affair was intense, obsessive, volatile. Trintignant was possessive, jealous, emotionally turbulent. Bardot was consumed.

When the relationship ended, she attempted suicide.The attempt was reported as melodrama. It was, in fact, despair. Bardot divorced Vadim in 1957. Though their marriage ended, Vadim’s role in her creation never faded. He had unleashed something neither of them could control.

Related story: From Bruce Wayne and Al Capone to an American Gigolo, Giorgio Armani made cinema elegant

Related story: Power, exits, debuts, and returns: The fashion moments that defined 2025

Marriage, motherhood, and rebellion

Seeking stability, Bardot married actor Jacques Charrier in 1959. It proved to be the most painful relationship of her life. Their son, Nicolas, was born in 1960.

Bardot struggled profoundly with motherhood. She spoke openly—brutally—about her discomfort, her ambivalence, her sense of entrapment. France recoiled. A woman could be sexual, a woman could be maternal, but she could not reject motherhood without punishment.

In 1973, at just 39, Brigitte Bardot did the unthinkable: she quit. No grand statement—she simply stopped acting.

The public turned cold. Bardot was labeled selfish, unnatural, monstrous. The marriage deteriorated into emotional abuse. Bardot attempted suicide again during this period. She eventually divorced Charrier in 1962, losing custody of Nicolas—a wound that never healed.

Artistry and resistance

Despite personal chaos, Bardot continued to work, often brilliantly. In La Vérité (1960), she delivered a performance of startling emotional vulnerability. In Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963), she became modernist iconography itself—aloof, luminous, emotionally opaque.

Yet Bardot resisted artistic canonization. She mistrusted critics, rejected intellectual frameworks, and despised being turned into a symbol. She worked instinctively, without reverence for cinema as institution. She refused gratitude.

Her relationships remained turbulent. Her affair with Serge Gainsbourg was brief but legendary. Gainsbourg adored her obsessively, composing songs that blurred eroticism and worship. Bardot recoiled from the mythmaking. She ended the affair decisively. Gainsbourg never recovered.

In 1966, she married German industrial heir Gunter Sachs, whose wealth enabled extravagant gestures—most famously, scattering roses over her villa from a helicopter. The marriage was glamorous, open, and emotionally shallow. They divorced amicably in 1969, as if concluding a mutually beneficial spectacle.

Walking away

In 1973, at just 39, Brigitte Bardot did the unthinkable: she quit. No grand statement—she simply stopped acting.

The industry was stunned. Stars were not supposed to leave while still desired. Bardot’s refusal felt like betrayal. In truth, it was survival. She later said cinema had taken everything it could from her. She would not give it her old age.

Free from cinema, Bardot devoted herself entirely to animal welfare. In 1986, she founded the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, committing her fortune, energy, and notoriety to the cause.

She campaigned ferociously—against seal hunting, factory farming, animal testing, and exploitation in entertainment. She lobbied governments, confronted institutions, and used language designed to shock.

Her compassion for animals was real, lifelong, and obsessive. Her rhetoric expanded into politics, immigration, and religion—often in inflammatory terms. She aligned with nationalist, far-right figures. She was convicted multiple times under French law for inciting racial hatred.

For many, these views shattered her legacy. For others, they were consistent with a woman who had never moderated herself for approval.

Final marriage and withdrawal

In 1992, Bardot married Bernard d’Ormale, a former political adviser. She withdrew almost entirely from public life, living in Saint-Tropez with animals, rejecting nostalgia, refusing interviews, uninterested in rehabilitation.

She aged outside the gaze. No reinvention, no monetization of her past.

Brigitte Bardot remains one of the most influential—and troubling—figures of modern culture. She pioneered sexual autonomy while rejecting feminism. She embodied liberation while suffering imprisonment. She loved fiercely, spoke recklessly, and refused correction.

Bardot’s life is not a morality tale. It is a warning about desire, fame, and what happens when a woman becomes too symbolically useful to be left alone.

History may never reconcile her contradictions. But it cannot erase them—and it cannot look away.

Bardot understood something few stars ever do: that nostalgia is another form of possession. To reappear was to be consumed again. Instead, she allowed her image to fossilize, untouched by the indignities of aging in public.

Related story: 19 most anticipated movies of 2026: Franchise comebacks and long-awaited adaptations

Related story: No more show FOMO