Too young for EDSA and too old for TikTok, I’m suspended between eras that measure cultural touchstones differently.

I’ve never truly felt that I belonged. Gen Xers tell me I’m a millennial; millennials tell me I’m too old for them. I’m the in-between, the almost-but-not-quite.

They call my kind the “Bridge Generation,” born in the late ’70s to early ’80s—those analog kids who became digital adults. Apparently, I exist to connect one world with the other. But I don’t like the term. I never volunteered to be infrastructure. I didn’t agree to be the duct tape between timelines or, worse, a government bridge project that’s forever “under construction.” At least I’m not a ghost project.

I’m not nostalgic for dial-up or desperate to go viral. I’m just here, standing in the middle, decoding both sides with a smirk. It’s not destiny—it’s survival. And unlike our actual bridges, I intend to stay structurally sound.

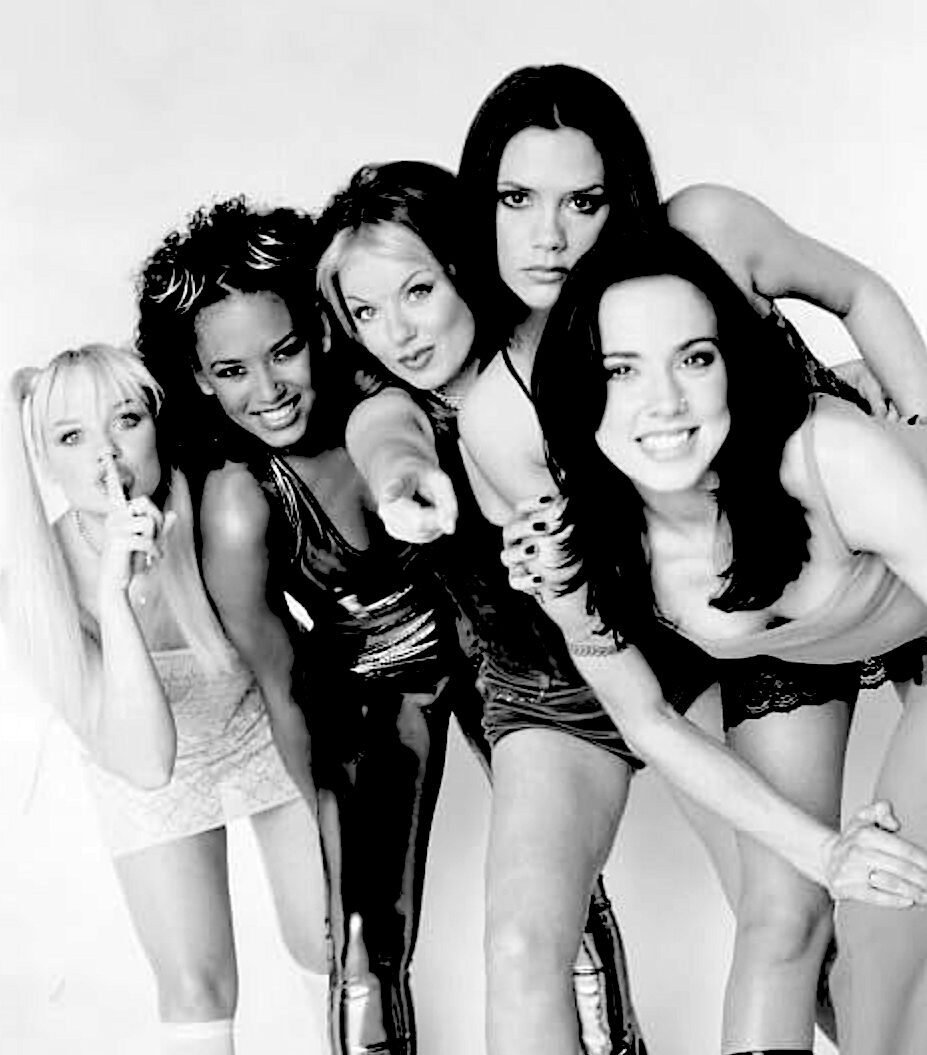

Maybe that’s why being stuck feels familiar. I was raised in contradictions. I loved The Craft and Clueless with equal devotion. I watched Daria on MTV but also tuned in religiously to House of Style, where supermodels were practically deities. I blasted Metallica and Nirvana, then shamelessly sang along to Spice Girls, Boyzone, and a little Miss Janet (if you’re nasty). I lived for the irony. Maybe that’s the curse—or the charm—of being a bridge. You don’t have to choose a side—you just have to hold both without collapsing.

Unlike my ates and kuyas, Ferdinand Marcos wasn’t my only president growing up. I had him but barely remembered much, then Cory and her energy crisis, FVR with the volcano and earthquake years, then Erap, whom I marched against in EDSA II when the envelope wasn’t opened. And GMA, who seemed to be president forever. By the time PNoy came, I was fluent in political déjà vu.

History, like pop culture, just kept remixing itself.

Related story: Did millennials follow their dreams after all?

Related story: Gen Z grew up online—now we’re tired of being perceived

Related story: Ours is better than yours: The long, petty history of the generation wars

Life in split screen

Being born in 1979 means living in a constant split screen. I remember when connection meant patience: waiting for cassette tapes to rewind, letters to arrive, or MTV reruns that aired weeks late. Now, connection means instant everything. I can message someone across the world in seconds, yet I still miss the quiet hum of waiting.

People say my generation got the best of both worlds: the grit of Gen X and the adaptability of millennials. But that’s just a polite way of saying we’re permanently in between—fluent in everyone’s language, but rarely spoken to in our own.

Then came grunge, and Kurt Cobain’s voice made sense in a way politics didn’t. I didn’t know Seattle, but I knew what loneliness felt like. That strange mix of wanting to belong and wanting to disappear was something I could name through music.

The first time I felt that split was during the EDSA years. I was five, chanting words I didn’t understand—just mimicking the cadence, delighted that the adults and teenagers seemed pleased.

“Diktadurang US Marcos, lansagin, lansagin, lansagin!”

I joined the chorus, clueless about lansagin. It sounded like something you yell before throwing a banana, which, to my five-year-old brain, made perfect sense. But even then, I felt the urgency. The adult and the teens shouted like history depended on their lungs. Maybe it did.

Then came grunge, and Kurt Cobain’s voice made sense in a way politics didn’t. I didn’t know Seattle, but I knew what loneliness felt like. That strange mix of wanting to belong and wanting to disappear was something I could name through music. I wasn’t rebelling like the older Gen Xers; I was just trying to find my place between their rage and rebellion, and the Millennials’ digital optimism.

Xennials

Writers and sociologists have called people like me Xennials or the Oregon Trail Generation—those analog kids who became digital adults. The term was first explored by Sarah Stankorb and Jed Oelbaum in GOOD magazine (2014), and later discussed by sociologist Dan Woodman in The Guardian. (2017). Cute, until you realize it’s just another way of saying “the middle child of history.”

Psychologist Alfred Adler once said middle children grow up adaptable but secretly crave affirmation (Understanding Human Nature, 1927). He wasn’t wrong. I’ve spent years adapting to everyone else’s pace—Boomers, Millennials, Gen Z—while wondering if anyone ever tried to adapt to mine.

Union Jack dresses, platform boots, and an unstoppable playbook: The Spice Girls didn’t just sing about Girl Power, they made it a global brand.

Being in between has made me observant. I know how to read a room, how to wait out a glitchy internet connection, how to balance politeness with irony. But it’s also made me tired. Everyone expects me to bridge the gap, to translate analog and digital, to understand both sides. No one asks if I want to.

I’m supposed to take pride in that flexibility, but sometimes it feels like invisibility. I understand why people call us the Bridge Generation, but I’d rather not be one. I’d rather be the landing, the space where things meet and rest before moving forward.

So yes, I was too young for EDSA and too old for TikTok. I’m not nostalgic for dial-up or desperate to go viral. I’m just here, standing in the middle, decoding both sides with a smirk. It’s not destiny—it’s survival. And unlike our actual bridges, I intend to stay structurally sound.

Related story: Are Filipino millennials more hopeful about marriage than their Asian counterparts?

Related story: From ‘delulu’ to ‘skibidi’: TikTok slang makes it into Cambridge Dictionary

Related story: The white-collar migration of Filipino millennials