Dissecting how a DPWH flood control project begins with public funds and ends in private pockets.

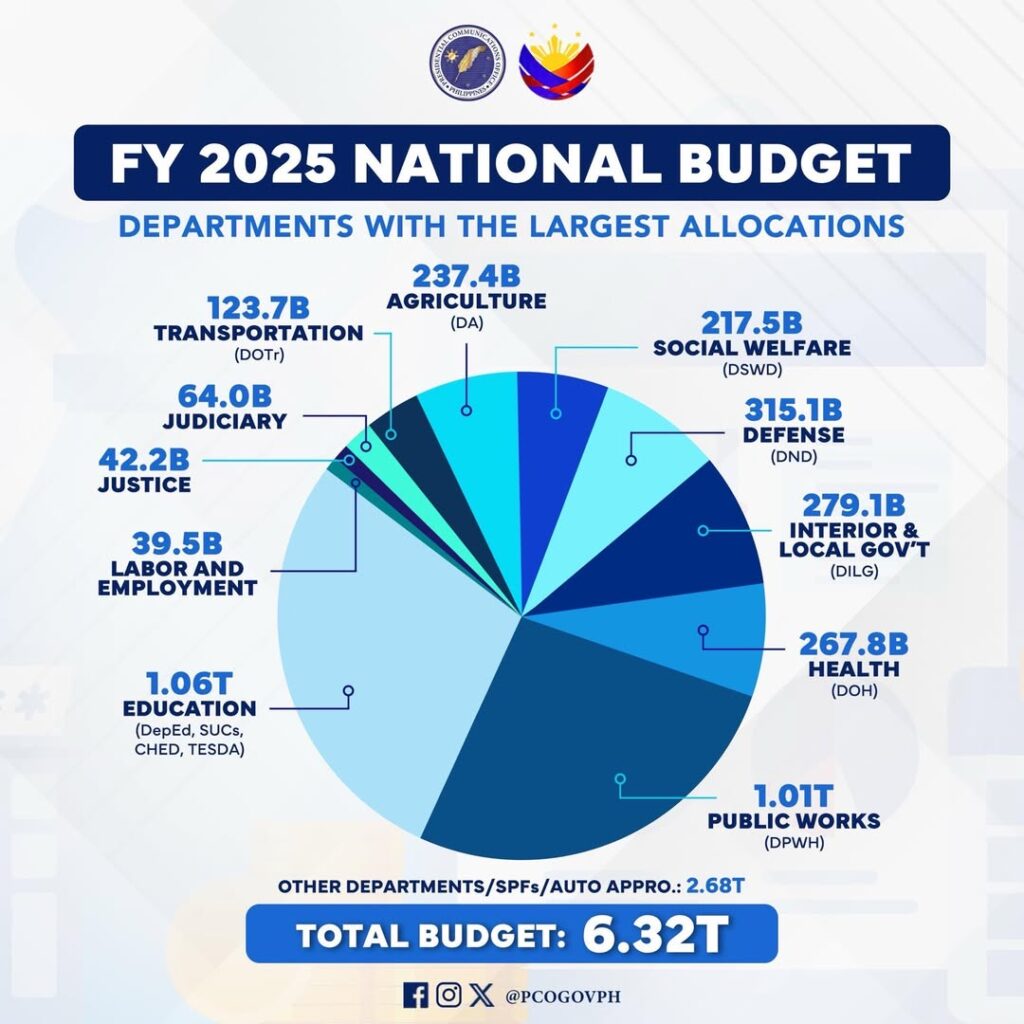

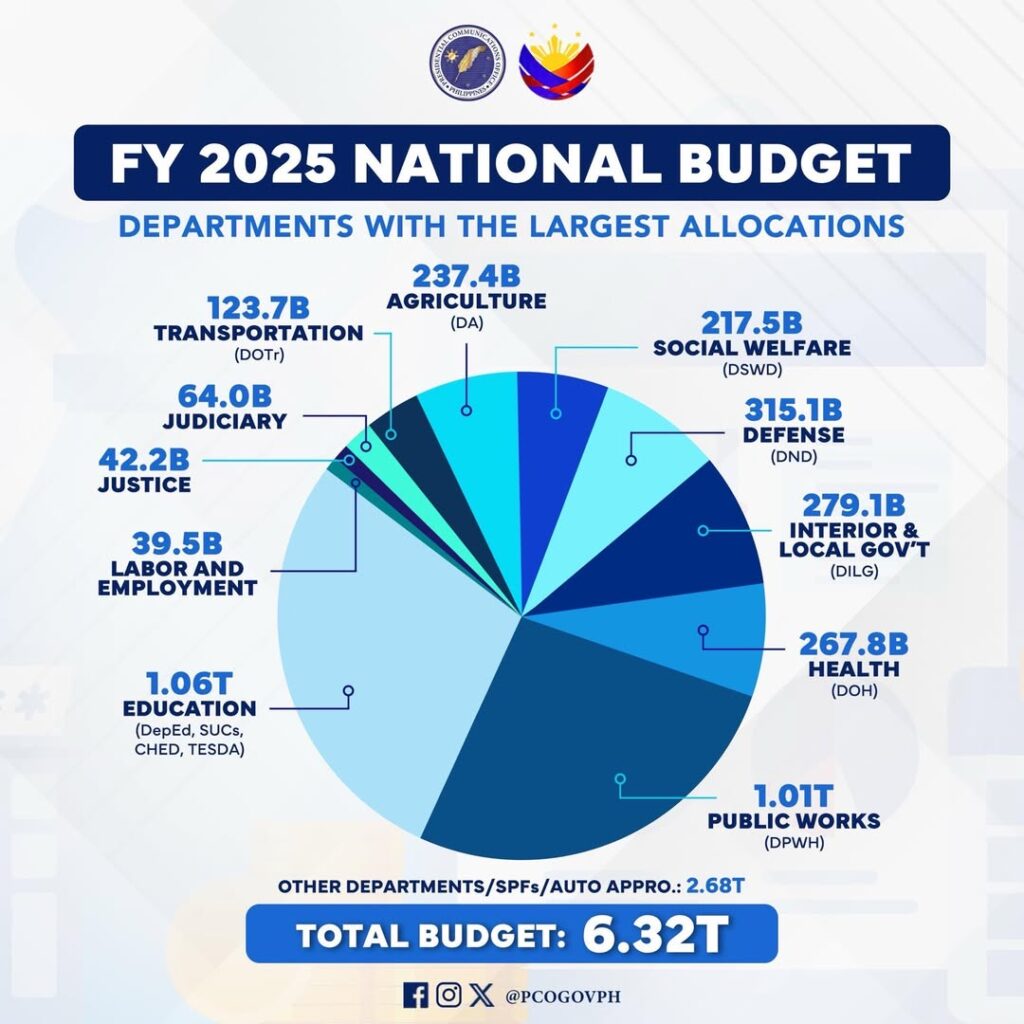

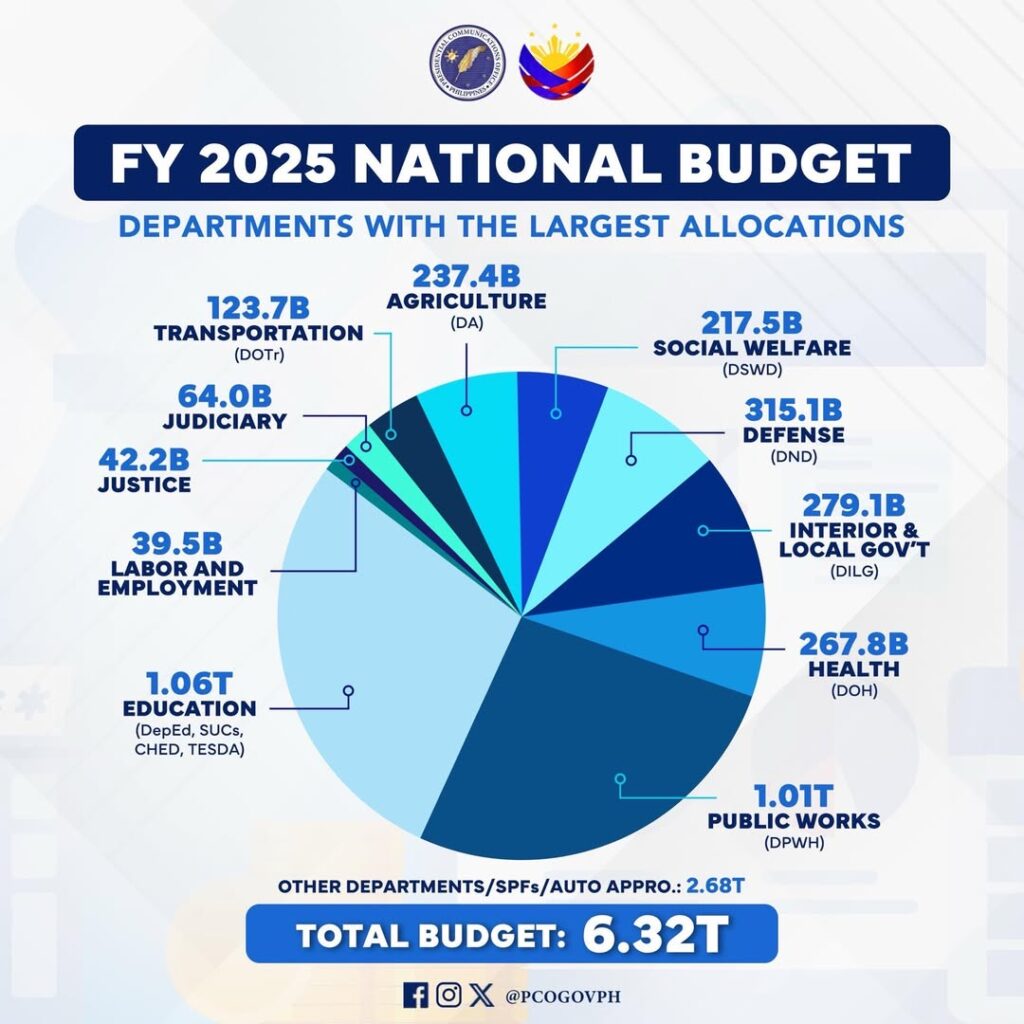

Roads, bridges, flood-control systems, schools—the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) builds them all. Out of the Philippines’ ₱6.3 trillion budget in 2025, DPWH got a staggering ₱1.01 trillion or 16.03 percent of the national budget, second only to the Department of Education’s ₱1.06 trillion.

From 2022 to 2024, DPWH had a budget of ₱786.6 billion, ₱893.1 billion, ₱822.2 billion, respectively. Secretary Manuel Bonoan headed DPWH since President Bongbong Marcos took office in 2022 until September 1, 2025—or over two weeks after the corruption in flood control projects was exposed on August 12, 2025. Before him, Senator Mark Villar served as department secretary under President Rodrigo Duterte’s term, from 2016 to 2021.

On paper, contractors must pass rigid requirements under the Government Procurement Reform Act; in practice, the door is wide open for fraud. Some firms are shell companies, existing only on paper with no equipment or workers, others are ‘rented‘ contractors.

Only after the public fury over recurring flooding in Metro Manila and display of wealth by contractors and their family members was Bonoan replaced on September 1, 2025. DPWH is now headed by Secretary Vince Dizon in an ad interim capacity.

In his first week in office, Dizon recommend plunder charges to the Ombudsman against former DPWH Bulacan heads Henry Alcantara, Brice Ericson Hernandez, and former chief of the district’s construction section Jaypee Mendoza. He also ordered a full scale investigation into the DPWH “mess” and banned certain contractors.

“This is obviously criminal,” Dizon said after inspecting alleged ghost projects in Bulacan. “This is plunder, almost P100 million stolen.”

That’s just the tip of the iceberg. And it all begins with a contract.

So many “safeguards,” yet billions still disappear

Behind the DPWH lies a well-oiled machine of rigged bids, substandard projects, and ghost infrastructures. By the time senators, congressmen, local officials, and contractors have carved out their cuts one way or another, so much money has been siphoned off that the project sinks the cities they were meant to protect.

To understand how billions of pesos are stolen from the projects, one must dissect how a DPWH flood control contract begins with public bidding with taxpayers’ money to fund it—and ends in private pockets as a scam, riddled with illegal campaign contributions, backdoor deals, and kickbacks.

Step 1: Qualifying as a bidder—the ghosts awaken

On paper, contractors must pass rigid requirements under the Government Procurement Reform Act (R.A. 9184), a valid license from the Philippine Contractors Accreditation Board; audited financial statements; proof of completed projects; and manpower capacity.

In practice, the door is wide open for fraud. Some firms are shell companies, existing only on paper with no equipment or workers. Others are “rented” contractors, where real, established firms lend their licenses to fly-by-night operators for a cut. Investigations in Bulacan, for example, spotlighted firms like Wawao Builders. The firm started with just one contract in Bulacan in 2021. However, in 2022, they won 15 contracts. Excluding DWPH projects, they secured 60 nationwide contracts from 2022 to 2025 worth ₱4.7 billion.

Step 2: The bidding—a theater of shadows

A DPWH bidding (like all government procurement in the Philippines) is required by law to be publicized so that contractors can participate. Here’s how it works:

1. PhilGEPS (Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System) The primary channel is PhilGEPS, the central portal for all government procurement. Under Republic Act 9184 (Government Procurement Reform Act), all invitations to bid must be posted here. Contractors can search for “DPWH” under procuring entities to see available civil works projects, bid notices, and awards.

2. Newspapers of general circulation Invitations to Bid (ITBs) are also published in at least one newspaper of general nationwide circulation. This is usually the classifieds or public notices section of broadsheets like the Philippine Star, Manila Bulletin, or Philippine Daily Inquirer.

3. DPWH Offices and Website DPWH Central Office, Regional Offices, and District Engineering Offices post physical copies of bid notices on their bulletin boards. The DPWH website also carries procurement announcements and bid documents for download.

4. Pre-bid conference announcements Once the bidding notice is out, DPWH schedules pre-bid conferences (announced in the same posting). These conferences are open to interested contractors to clarify project requirements, timelines, and qualifications. Public bidding is supposed to ensure competition but a lot of questionable companies still land contracts because of:

• Bid rigging: Contractors secretly agree among themselves who will “win,” while others submit overpriced or deliberately flawed bids.

• Leaked ABCs: The Approved Budget for the Contract—supposedly confidential—somehow always leaks, allowing favored bidders to submit offers just slightly below the cap.

• Ghost bidders: Paper firms with no offices, no trucks, and no track record join the lineup to simulate competition.

• Technical knockouts: Real competitors are eliminated for minor errors like missing a signature or misplaced page, while the chosen contractor sails through.

By the time bids are opened in front of cameras, the outcome has long been decided.

Step 3: Project award—from kickbacks to collapsing walls

A DPWH contract award is issued only after the entire bidding process is completed and the “lowest calculated responsive bidder” (LCRB) has been confirmed.

The timeline under the Government Procurement Reform Act (RA 9184) as applied in DPWH: Bids are opened publicly at the scheduled date. The Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) evaluates and ranks bids. The lowest bid is identified as the Lowest Calculated Bid (LCB).

The LCB undergoes a post-qualification check, DPWH verifies eligibility documents, technical capacity, financial standing, and past performance. If the LCB passes, it becomes the Lowest Calculated Responsive Bid (LCRB). If it fails, the next lowest bidder is evaluated, and so on.

Once the BAC recommends the winning bidder, the Head of Procuring Entity (HoPE)—in DPWH, usually the Secretary, Regional Director, or District Engineer—issues the Notice of Award (NOA). Timeline: RA 9184 requires this to be issued within 7 calendar days from BAC recommendation.

After the NOA, the winning contractor must submit: performance Security (5–10% of contract price); other required documents (insurance, clearances, etc.). The contract is then signed between DPWH and the contractor. Timeline: The contract must be signed within 10 calendar days from the contractor’s receipt of the NOA.

After contract signing and submission of the Performance Security, the Notice to Proceed is issued. This officially marks the start of the project implementation. Timeline: The NTP must be released within 7 calendar days from contract approval.

A DPWH contract award (NOA) is issued after post-qualification, once the BAC confirms the winning bidder. By law, it should be given within 7 days of the BAC’s recommendation, followed by contract signing (10 days) and Notice to Proceed (7 days).

When the award notice is issued, that’s when the real money game begins. Kickbacks are sliced up: a portion for corrupt DPWH insiders, a portion for corrupt local politicians, sometimes even a “thank you” fee for auditors.

The contractor, having promised millions in cuts, must now recoup. The standard playbook: subcontract the project at half-price. The result? A ribbon-cutting ceremony for a road already cracking under its own weight.

Senator Panfilo Lacson, in his August 2025 speech, said only 40% of the total project value goes into actual work with the rest siphoned off as kickbacks, often up to 60%. If we use the ₱1 trillion DWPH budget in 2025 as an example and divide it by 60%, we can calculate that ₱600 billion pesos was stolen from taxpayers’ money through DPWH projects in 2025 alone.

Related story: OPINION: Worshipping the rich, the beautiful, and the hopelessly vacant

Related story: SPECIAL REPORT: Unpacking the NAIA price hikes

Step 4: Execution—or the lack of it

Two scam models dominate implementation. Substandard projects: Instead of proper gravel, cheap quarry fill. Paint jobs that peel within months. Bridges with undersized steel. Inspectors, often complicit, sign off anyway. One such example is a bridge in Zamboanga that collapsed with government officials on it. Ghost Projects: This is the cruelest trick. Funds are released, papers are signed, reports are filed, but on the ground, nothing exists. The “completed barangay hall” is still an empty lot. The “farm-to-market road” is still a muddy trail. One such example is a recent project that President Marcos visited in Bulacan.

Step 5: The paper trail and the great cover-up

Audits arrive months or years later. By then, the paper trail looks pristine: receipts are forged, progress photos are recycled from other sites, inspection reports are mass-signed.

Even when anomalies are caught, discussed in senate hearings with the promise to prosecute those responsible, politicians and officials that allow the scams to continue are not jailed (or if they are, as in the case of the Napoles scam, they are set free). This stays in the news until public outrage fades, and the roads collapse faster than accountability arrives.

The cost of corruption

Every peso lost to a DPWH scam contributes to a collapsed bridge, a farmer stuck in the mud, a classroom that never gets built. This isn’t just corruption in abstract numbers—it’s corruption that bleeds into the daily grind of ordinary Filipinos.

DPWH, senators, congressmen, contractors and government bureaucrats protect a system that’s less about infrastructure and more about patronage and plunder. Projects aren’t built for the people—they’re built for profit, political loyalty, and personal gain.

Until transparency is enforced and political will matches the public frustration, DWPH will continue to build wealth for the few—and broken promises for everyone else.