A picturesque village in Cornwall is home to one of the most unique museums in the world, blending history, folklore, and the occult.

“We are the weirdos, mister” is a line that every girl who grew up in the ‘90s knows. We played “light as a feather, stiff as a board.” Fancied ourselves as reluctant albeit powerful witches, like Robin Tunney’s character, Sarah. Everything comes back to you threefold.

I can guarantee that most girls went through a Wiccan phase. It seems only natural. After all, women throughout history are often associated with the divine — revered as goddesses, feared as witches.

Stepping into Boscastle made me want to say to all my girlfriends, “Sisters! I have found the place where we belong.” I can guarantee that most girls went through a Wiccan phase. It seems only natural. After all, women throughout history are often associated with the divine — revered as goddesses, feared as witches.

I once said to my husband that I’ve noticed how women, as we grow older, seem to turn into witches! Not in the stereotypical sense. With time, the need to explain with logic how we feel has lessened. For example, I listen to my intuition more, avoid talking about other people lest I cast energy their way, and schedule haircuts around the dreaded Mercury retrograde. After all, a little guidance from the universe couldn’t hurt.

I see it more often now: girls with tote bags while sipping matcha lattes and doing tarot pulls in cafes. People showcasing impressive crystal collections on Instagram, online stores stocked with sage and palo santo to cleanse your space, Fully Booked with a whole tarot card section, and other reminders that New Age practice is no longer taboo.

Taboo as tourism

Stepping into Boscastle in Cornwall made me want to breathe in and turn to say to all my girlfriends, “Sisters! I have found the place where we belong.” There are mini art galleries, craft stores, a large pottery shop, traditional pubs and tearooms, and a random second-hand bookshop built with stone. But what makes Boscastle different from other historic villages in the United Kingdom? Most of its tourists choose to visit for a specific reason, but the large number of shops selling Wiccan and occult items plain as day can still be startling. Wiccans and fans of the esoteric will be spoilt for choice of wands, charms, crystals, literature, and even cauldrons.

This quaint harbor village is rich in history and folklore, fueled by carvings of labyrinth petroglyphs nearby, estimated to be from the Early Bronze Age (1800-1400 BC). The 2021 census reported that Boscastle had a population of 706. Pre-pandemic, it attracted around 49,000 visitors a year. Much of it due to the pilgrimage of practitioners from all over the world to the village’s famous Museum of Witchcraft and Magic. Yes, famous, because the village completely embraces and protects the museum and much if its identity is tied to it.

Related story: From prison to posh: Would you stay where prisoners were once hanged?

Related story: The top 10 scariest Asian horror films of all time

The Museum of Witchcraft and Magic

Although it was the height of the British summer, the skies were overcast on the day of our visit. The River Valency runs merrily alongside the the village that’s dotted with stone-built cottages dating as far back as the Elizabethan era.

The museum is small, and if not for the image of a witch on a broomstick, you would think it’s a normal charming house painted white, surrounded by flowering shrubs.

I was unsure of what to expect stepping inside. As someone who was raised Catholic, I had apprehension being so close to the occult. Did I expect devil-worshipping materials? Maybe. While my husband bought the tickets, the ticket seller turned to me and asked if I wanted a digestive. Not really. He shook the box at me and insisted. Was this a test? Was there some sort of spell in the biscuits? Should I accept it? I did, dear reader. My imagination runs wild at times.

Low ceilings, floors that creak with every step, narrow passages. The corridor is a journey through many aspects of the occult, from fae to witchcraft. It’s important to highlight that its founder, Cecil Williamson, wanted to shine light on folk magic—the charms, spells, and rituals of ordinary people. Much of magic is sensationalized and demonized, which often overshadows what comfort it brings to people, past and present. Exploring the museum shows the little things that humans do to tempt fate in their favor. A way to gain control of their lives.

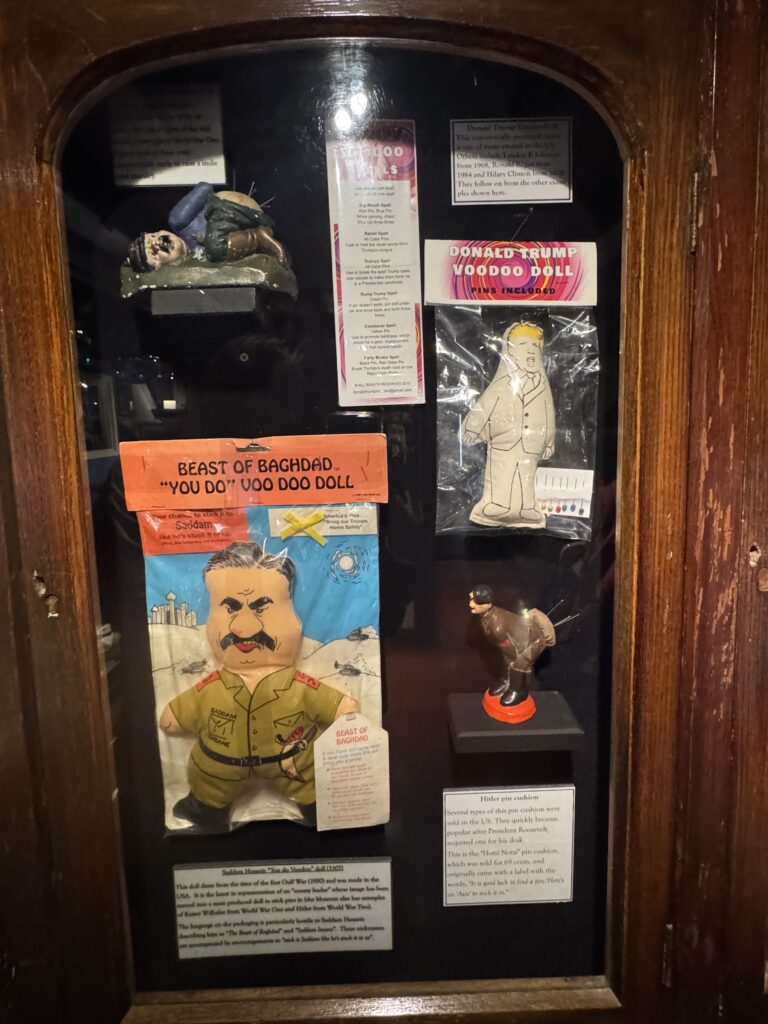

Displays are arranged according to theme, but also the progression of witchcraft and its standing in society over time. I’ll admit, I skipped taking photos of some displays, including the “Curses” section, which I did not want to particularly live in my gallery. Surprisingly, there was even a voodoo doll of Donald Trump, complete with instructions on usage.

Noteworthy displays include “Joan’s Cottage,” a reconstruction of a cunning (pellar in Cornish) woman’s cottage. The term “cunning” is a historical reference for a folk healer, who uses herbalism and folk magic to help people with issues such as sickness and protection from harm. Cunning folk avoided persecution because the common people saw them as helpful, while branding witches as harmful.

The museum does not shy away from the dark history of the witch trials. The exhibit includes a selection of witch-hunt and trial instruments, including documentation of witch trials in the early modern period. On display is an iron weighing chair, incorporating a balance holding a two-volume “Southwell’s Family Bible.” Its premise was simple: witches can fly and therefore are lighter. If the accused is heavier than the bibles, they are released. For example, in 1780, the inhabitants of Bexhill had a clergyman weigh two women against the Bible, who, of course, were heavier, and thus freed.

I see it more often now: girls with tote bags while sipping matcha lattes and doing tarot pulls in cafes, people showcasing impressive crystal collections on Instagram, and other reminders that New Age practice is no longer taboo.

Despite its unsettling presence, the chair is thought to have a more compassionate purpose. Local clergy were thought to use it to satisfy the superstitions of angry mobs, effectively protecting and saving the lives of the accused.

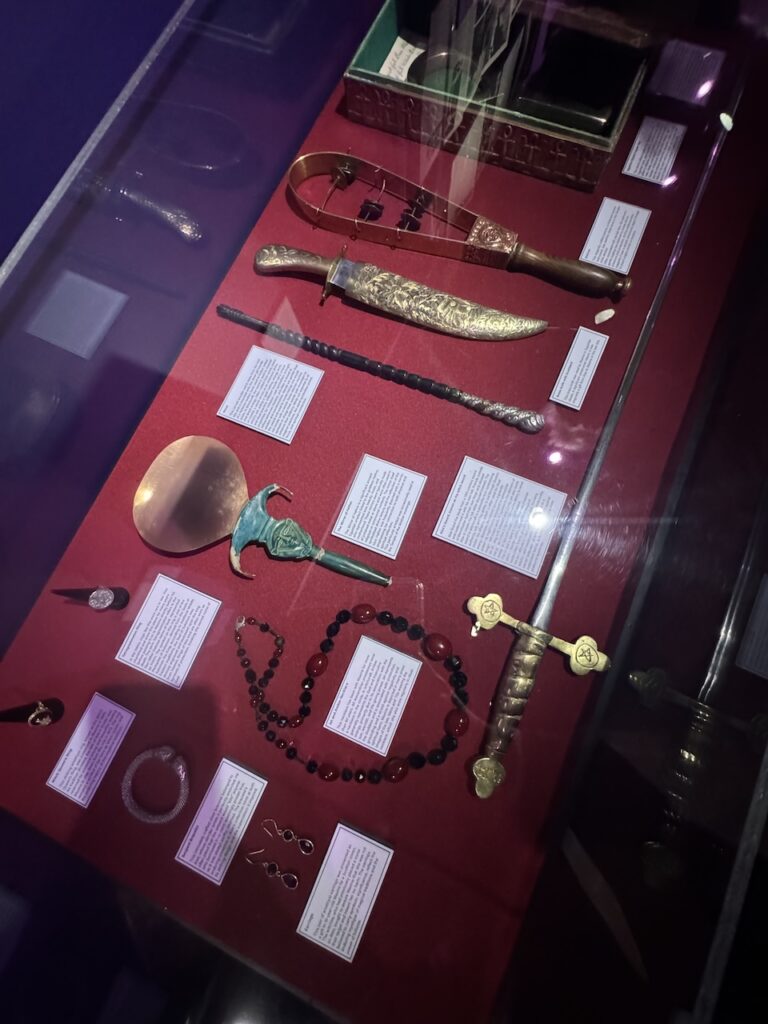

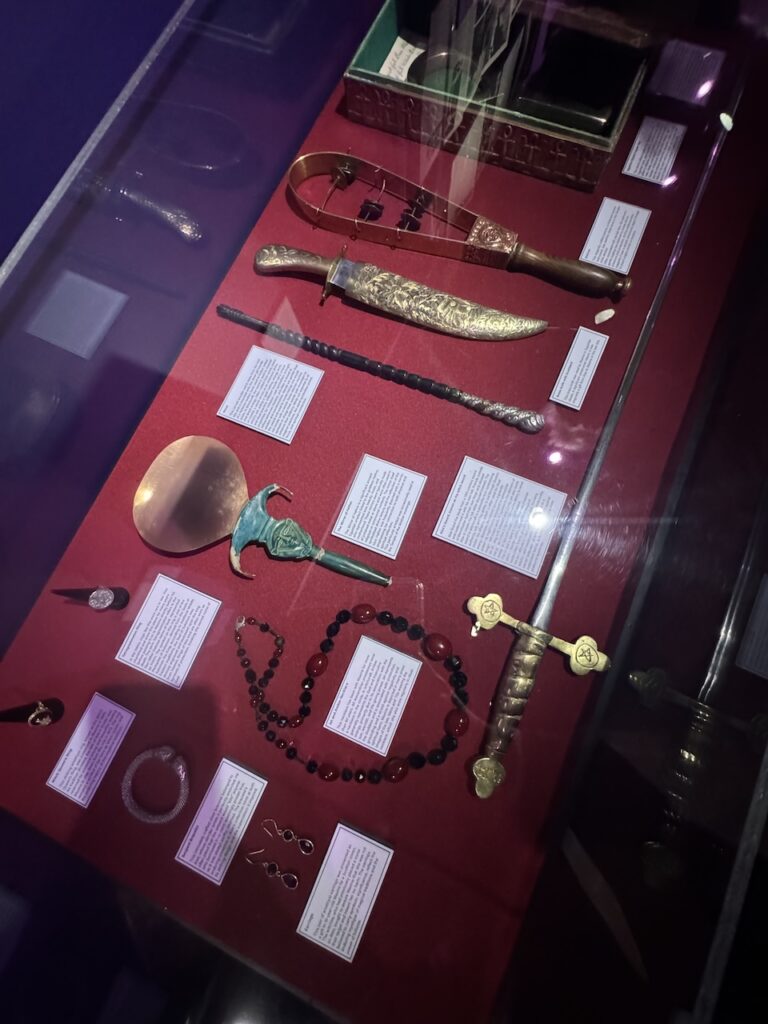

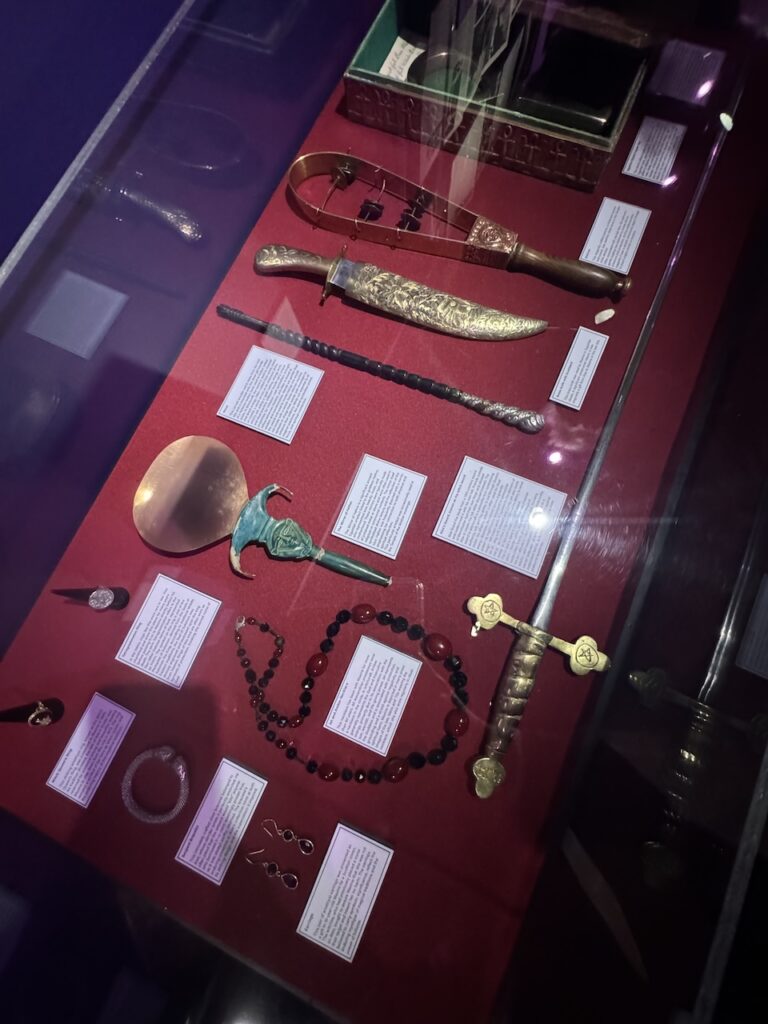

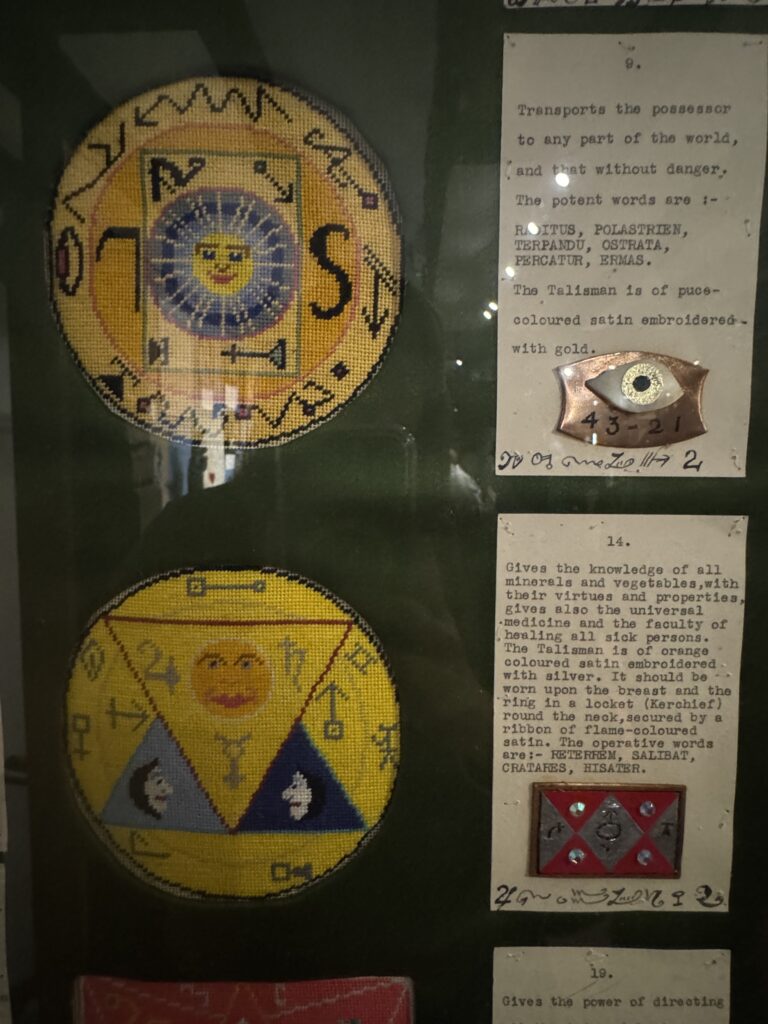

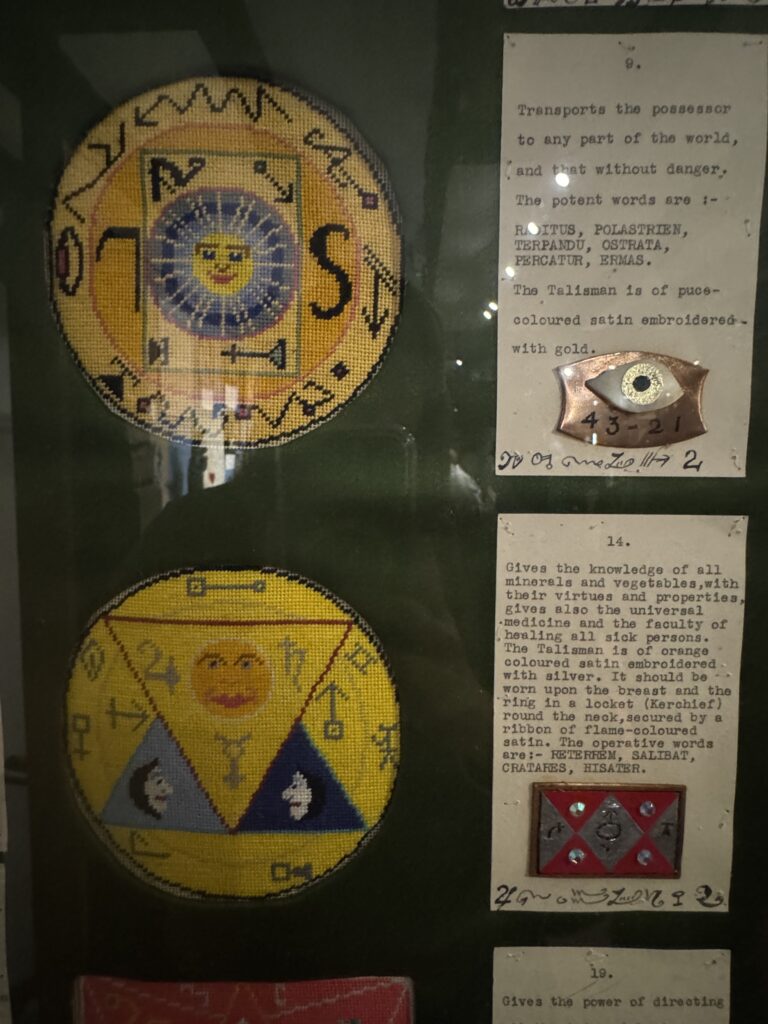

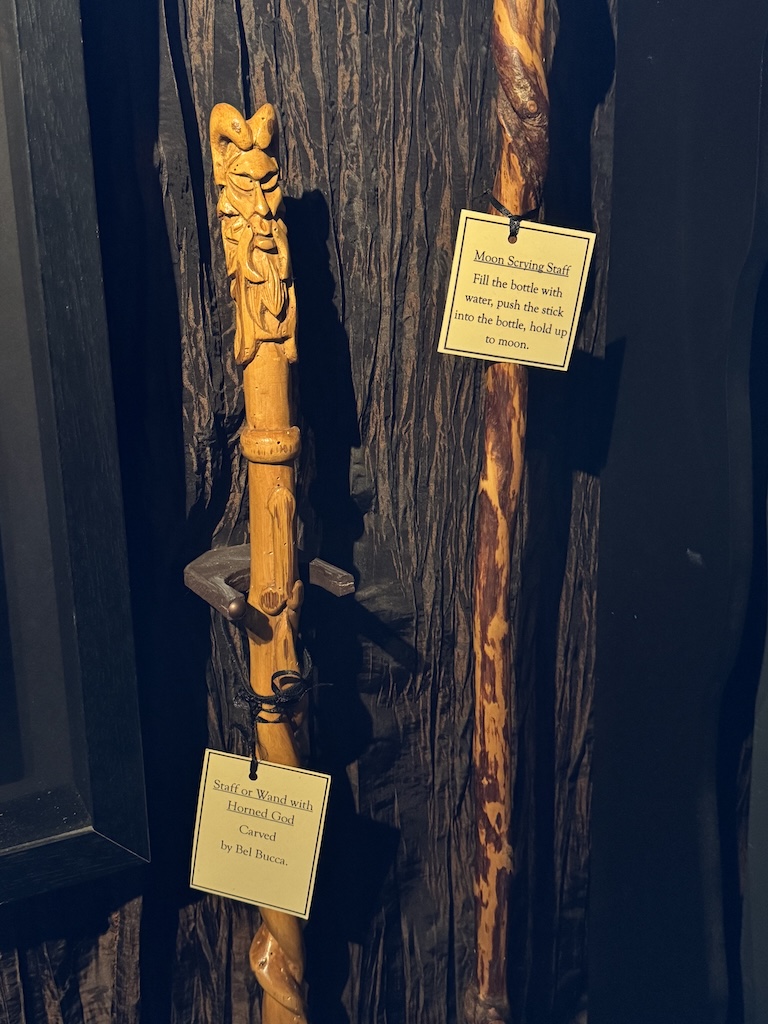

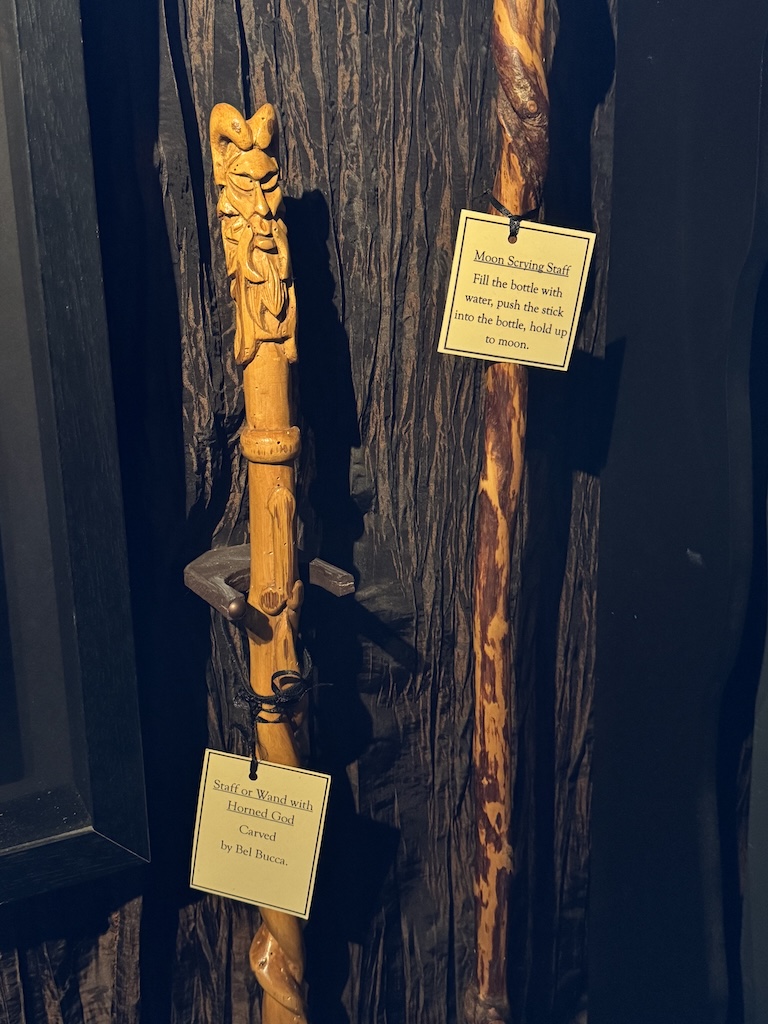

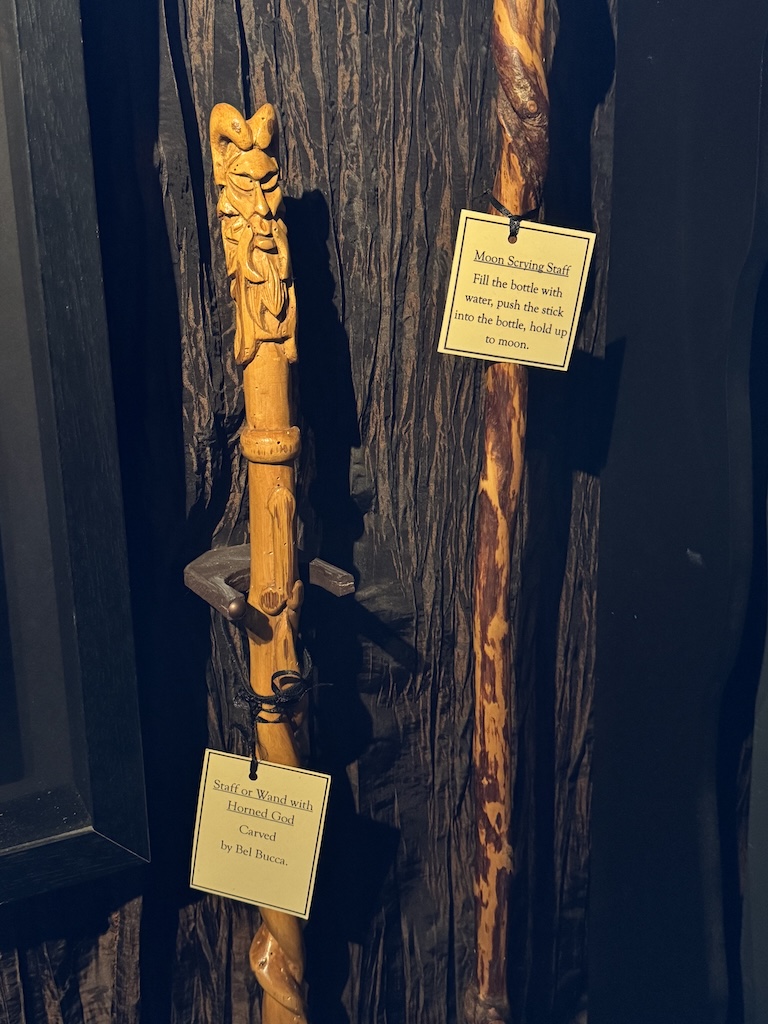

Williamson was largely interested in “wayside” witchcraft, a traditional type that uses ingredients easily sourced from fields and woods to use for magic and healing. It’s no surprise that there’s a large collection of folk charms and magic tools, ranging from witch bottles (sealed with pins, urine, and items such as hair and nails and believed to ward off evil spells), poppets (handmade dolls for healing and cursing), scrying mirrors, Ouija boards, and more.

There’s also a fascinating display of occult relics from famous witches and magicians in modern magic. Crowns, chalices, wands, talismans, masks, and more tools used by prominent occultists. This includes a ritual chalice by Aleister Crowley, and a ritual sword and inscribed altar slab owned by “King of Alexandrian Witches,” Alex Sanders, to name a few.

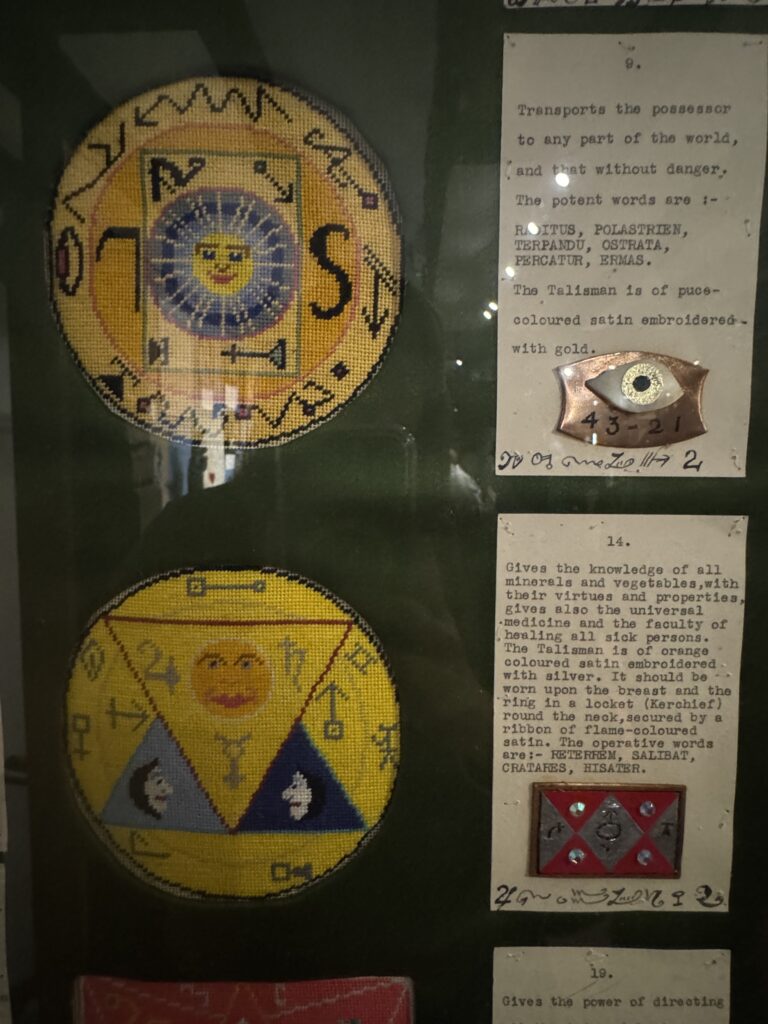

The museum also catalogued the vast Richel-Eldermans collection, comprising 2,500 images and artifacts created by J.H.W. Eldermans, later inherited by his son-in-law, Bob Richel who added his own works in the collection. Not much is known about Eldermans, but according to Richel, he was Magister in a lodge of the magical order A∴A∴ in the Hague and Leiden. This could refer to the orders of Aleister Crowley’s ‘Argenteum Astrum’ or the ‘Ars Amatoria’. The collection is described as enigmatic, highly sexual, and erotic in nature.

There is also a whimsical display documenting beliefs about the fae, from fairies to piskies, and more. Despite its size, the museum holds thousands of collections. Independent research is encouraged, and interested parties can even book time in their library. The collection continues to grow; with contemporary practitioners even willing their working tools to the museum. For example, there is a Book of Shadows that was owned by an elderly gentleman who gave it to a witch. After 12 years and an unfortunate incident, the witch donated it to the museum in 1998.

A spellbinding past

It’s no surprise that the museum’s founder was a fascinating man himself. Cecil Williamson had multiple brushes with the occult as a child, which continued to adulthood. There was even one point in his life when he learned African witchcraft while working in a tobacco plantation in Zimbabwe.

He spent some time in the British film industry, and eventually approached and hired by the British Secret Services to collect information on Nazi occultists. This participation gave birth to “The Witchcraft Research Centre.”

His first attempt to open a museum was at the Stratford-upon-Avon in 1947, but was met with local opposition; his second attempt at the Isle of Man was more successful. Williamson then hired fellow enthusiast Gerald Gardner to be the museum’s resident witch. During this time, the government repealed the Witchcraft and Vagrancy Acts in June 1951. This meant that it was now a crime to claim that any human being had magical powers.

This relationship was tumultuous and short-lived, and the two parted ways. Williamson returned to England where he made multiple attempts again to find a home for his collection, facing more opposition, acts of vandalism, and even an arson attack. This search stopped when he finally found a home in Boscastle. It was the perfect place to settle. The rugged Cornish coast was hospitable and beautiful, the locals were tolerant and accepting, and the nearby presence of mystical carvings were reassuring.

Passing the torch on Hallow’s Eve

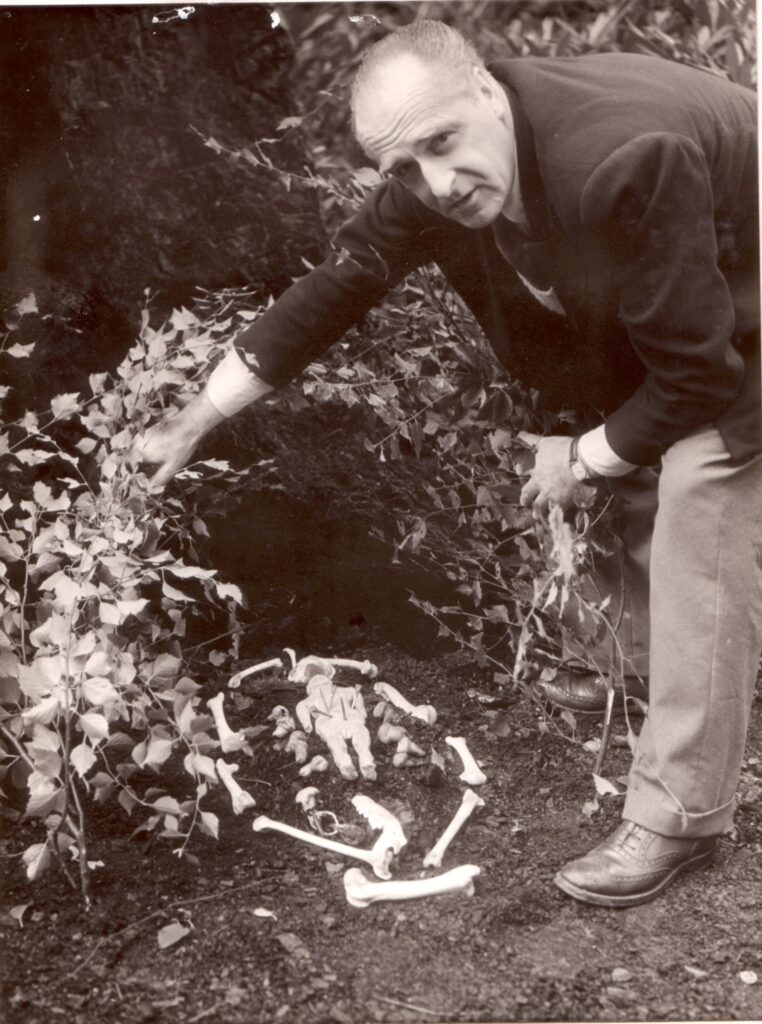

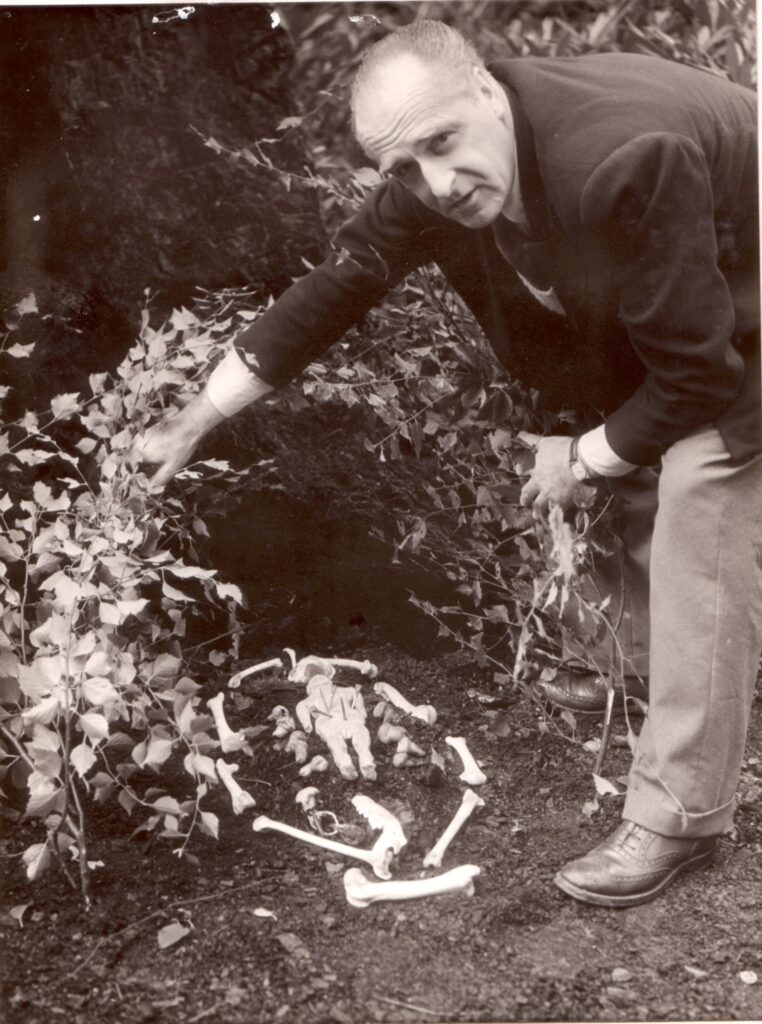

In 1996, Williamson was ready to retire and he sold the museum to practicing pagan, Graham King. And what better timing than to complete the sale at midnight on Halloween? After King took over, he and his partner Liz Crow removed the more kitschy and sensational displays. The purchase of the museum meant also dealing with an ethical dilemma, the display of the skeletal remains of Joan Wytte.

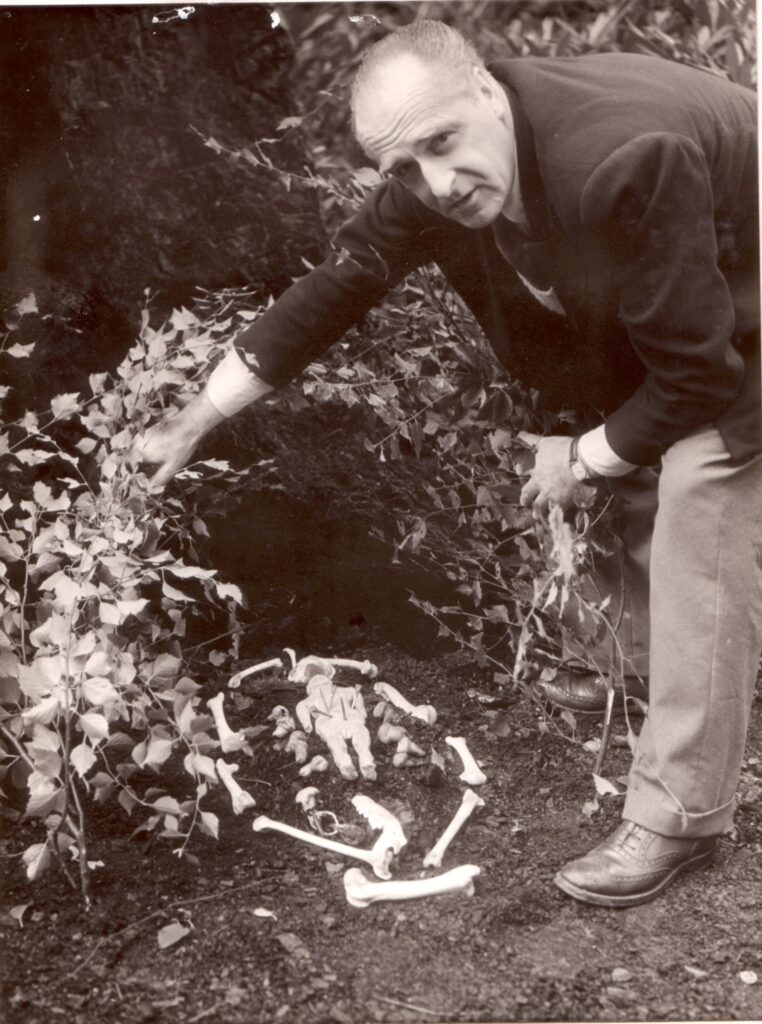

Joan was an 18th-century Cornish woman with the nickname “fighting fairy of Bodmin.” She was said to be skilled in healing and divination, and widely known for having a fierce temper. She was accused of being a witch and died in the infamous Bodmin Jail at the age of 38. Her remains were said to be used in seances, and eventually locked away until it was acquired by the museum. She was displayed there for many years until King arranged for her to be given a proper burial in the woodlands near Boscastle in 1998.

collection of palmistry tools and divination tea cups

The locals accepted the museum, but it wasn’t until a once-in-a-century flood on August 16, 2004 that cemented its relationship with the village. King was the one who raised the alarm, allowing much of the residents and visitors to escape. In the aftermath, the community stepped up to save its unique museum. Staff and volunteers worked together to help in its recovery. Miraculously, it reopened with new exhibition spaces, along with renewed interest in the museum driving record numbers of tourists into the village.

On Halloween 2013, the museum changed hands again. Simon Costin, a designer and curator, took over the ownership of the museum’s collection from King. We reached the end of the exhibit in complete awe, slightly disturbed, but with a better grasp of another world. Regardless of personal beliefs, this much is true— Boscastle and the museum proved that even in the modern world, magic still has a place.

As for me? I happily went home with a tote bag and a keychain plushie of a black cat from the museum gift shop.

For more information, visit https://museumofwitchcraftandmagic.co.uk/.

Related story: Here’s your Halloween 2025 costume inspo—from K-Pop Demon Hunters to Taylor Swift’s showgirl glam

Related story: Halloween 2024: Celebrities pull out all the stops for nostalgia, glamour, and fun