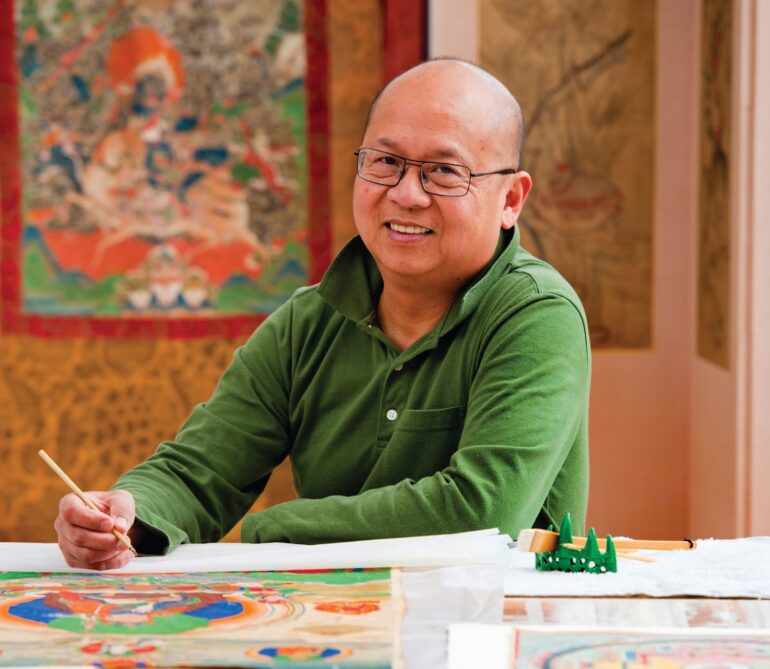

Filipino art conservator and educator Ephraim ‘Eddie‘ Jose wants to pass down his knowledge to different art institutions.

In the 2016 documentary 1000 Hands of the Guru, we follow a conservation team as they embark to preserve ancient Tibetan Buddhist scrolls known as the thangka. Intricately painted yet usually unframed and prone to improper care and storage, these thangka paintings have been passed on from generation to generation, serving as a repository for historical and spiritual storytelling. The documentary traces a team of conservators and monks as they attempt to restore the thangkas to their former glory.

A key figure in the restoration journey of the thangka scrolls is the Filipino art conservator and educator Ephraim “Eddie” Jose. Over the course of over four decades, Jose trained in the rigorous art conservation traditions of Japan, with specializations in restoring and mounting Asian works on paper and fabric. “Cleaning thangkas is a delicate task,” Jose recalled. “Over time the monks have learned not to over-clean, so as not to lose the character and patina of the original art.”

Last November 25, Jose, who was wearing his traditional Japanese garments, gave a lecture and demonstration on the intricate art of conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Manila in Taguig City. The two-hour session was the first in a series of in-depth discussions on art conservation, held in conjunction with the museum and the De La Salle University-Dasmariñas Center for Heritage Conservation. Accompanied by his apprentices from the heritage center, Jose was an inviting and engaging presence throughout, freely answering questions from the audience with rigor and enthusiasm.

Sharing insights from his four decades-long career on conservation, Jose began the session with a quick lecture on his background. An itinerant art enthusiast, Jose’s art conservation career began in Japan where he learned Japanese techniques of paper restoration under the tutelage of Japan’s most respected master restorers. Eventually, he started working on museum collections, applying his learnings to the art institutions across the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and perhaps most notably, Bhutan, where he trained the first set of monk conservators of the thangka.

“My goal has always been not just to train this first generation of monk conservators, but also create a tradition of conservation that they can pass to subsequent generations,” Jose remarked, underscoring the crucial task of passing down his valuable restoration learnings acquired all over the world. “Who better to restore sacred religious art but the monks themselves?”

Recalling his own attempts to strengthen the heritage conservation efforts in the Philippines, Jose stresses the importance of offering the next generations opportunities for engaging with conservation on a practical level. “Though it’s a lot of hard work, it’s very important to impart my knowledge to the young people in the Philippines,” Jose said during the lecture as he reminisced how he returned to the Philippines after spending the majority of his life abroad. Throughout the demonstration, Jose called on his apprentices to assist in the various preparation processes, which ranged from feathering the washi paper (a gentler way of cutting paper), treating the polyester sheets, and concocting the vegetable starch base to be used for glue.

Towards the end of the demonstration, Jose remarked that part of the difficulty of conservator work is that it is mostly “under the table work.” Often, the meticulous and highly complex processes of conservation and restoration go unnoticed by the general public. These processes are also very demanding of time and patience, from allowing drying to take place, framing, and extracting acidity: these all require restraint and perseverance in letting these processes unfold in their own time. “My only consolation is when I see the paintings on display,” Jose said, “when I get to see their pristine condition.”

Returning to the Philippines with the determination to cultivate a new set of conservators, Jose said he wants to give back and pass down his knowledge obtained over the years, throughout different art institutions. February this year saw the launch of the Center for Heritage Conservation at DLSU Dasmariñas, which aims to provide art conservation services through holistic and scientific approaches, serving as a dedicated space for providing heritage conservation education.

With Jose working as a senior lecturer, conservator, and consultant at the center, he is ultimately extending his learnings to the broader community, keeping the labyrinthine yet necessary legacies of conservation alive.