In their risk-taking, cosmopolitanism, and full-bodied experimentation, two dance acts light a path forward in reimagining Filipino dance.

A masked woman—a creature of light, really—sits on the floor, her fingers stretched out into a bony lattice. The body on the floor momentarily and rhythmically inhales, a presence siphoning off the room’s available energy. Then, a sudden snap, the exhale. Her hands reach out, it seems, for the heavens. For some ineffable secret unknown perhaps even to her. Despite the recording’s graininess, the woman’s angular and animalistic movements cut through all the static.

Originally choreographed in 1914, the German dancer Mary Wigman’s Hexentanz distilled dance into its most primal tincture: the intuitive expression of movement, unencumbered by theatrics or repertoire. Seeing Wigman dance the Hexentanz (also known more widely as the Witch Dance) is to witness a body launched into a precipice of complete surrender. A witch exuding her austere and mystic powers.

Babae, dancer Joy Alpuerto Ritter’s solo work held at the CCP Black Box Theater last January 27, takes on Wigman’s witch dance—its carnal rhythms and emancipated energy—and recontextualizes it, crafting a diverse choreography through the personal and social history specific to the Filipina’s lineage.

Ritter has said that she felt a physical connection with the Hexentanz as early as her teens (she first performed Wigman’s dance at the age of sixteen). Years later, with Babae, Ritter choreographs a dream sequence of ritual and revelation, drawing upon an extensive vocabulary of dance styles from contemporary and hip-hop to voguing and Philippine folk.

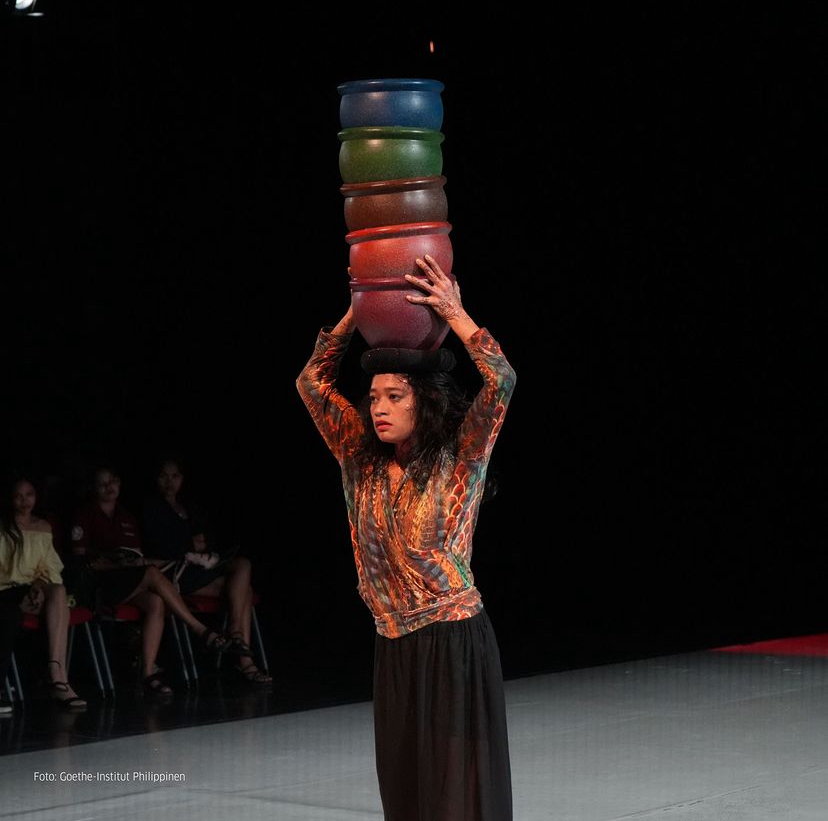

Ritter, a svelte yet forceful presence, commands the stage. Early into the performance, the dancer dips her hands into five pots, each one flickering alive upon her touch. These pots, a recurring motif throughout the dance, signify the five elements of nature. Stacked together over Ritter’s head at one point, Babae emerges as Ritter’s attempt at unifying those elements, at finding a sense of footing amidst incongruity. “I wanted to showcase the woman not as a victim but as a strong and fragile and sensitive character,” she explained during the talkback.

In another rousing moment, Ritter’s hands morph into bird-like creatures conversing and bickering above her head. The resourcefulness by which Ritter wields her body—her acrobatic leaps, vigorous squats, and ardent eye contact—attest to the dancer’s unique blend of intelligence and inventiveness. Vincenzo Lamagna’s prismatic musical accompaniment, full of striking drums and guttural drones, magnify Ritter’s esoteric movements.

Ritter’s Babae is but one-half of the night’s twinbill show titled Joy & Daloy. After a (very welcome) ten-minute intermission, the lights of the Black Box theater darkened once again to ring in five performers. Daloy Dance Company, spearheaded by director and writer Ea Torrado, exhibited ItikLandia, a performance partially inspired by the traditional folk dance itik-itik. Where Ritter’s performance striked me as supercharged by a spiritual and intimate knowledge of the self, ItikLandia turned its gaze topically, looking outward at the ways in which environmentalism is performed today.

Themes of climate justice and capitalist critique are the most prominent points of reference for ItikLandia but it filters those heady topics through a gaudy sense of humor that borders on kitsch. Torrado, last year, described the dance as a “a physicalized hymn to the natural world we all share, live, and thrive in.” But that word hymn doesn’t quite get at the piece’s sheer, and defining, quality of fun. The production—at one point, the floor projected a mass of ducklings—took on a lighthearted and kooky hue, and the performances—a standout was a stoned rendition of Bahay Kubo processed through a vocoder—gleamed with downright delight.

ItikLandia’s staging of dance, though mostly surefooted and expressive, did not necessarily occupy the work’s pride of place. Elements of production, song, and audience interaction, instead, seemed to govern the piece, and to genuinely engaging effect. During one moment, we were prompted to put our cellphone flashlights up in the air and quack along with the performers. The result of this type of composition is that of a crossover between a rave and a parent’s night dance show—equally immersive, irreverent, and occasionally didactic.

Seeing Babae and ItikLandia one after the other, it’s easy to read them as counterpoints: one partaking in a more expressionist tradition, while the other more straightforwardly dramatic and theatrical. But I believe the more enriching reading would be to examine these works’ contrasts as convergent tendencies of contemporary dance: in their risk-taking, cosmopolitanism, and full-bodied experimentation, these two dance acts light a path forward in reimagining how Filipino dance can respond to the entangled worlds of the personal and the social.