The Nobel laureate was awarded the prize for her poetry whose “austere beauty makes individual existence universal.”

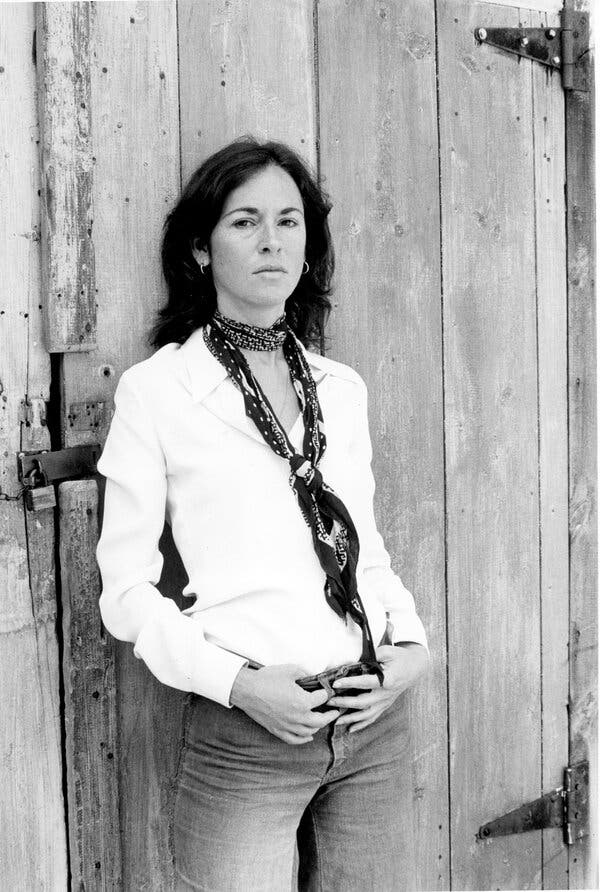

Last October 13, the widely acclaimed poet, critic, and teacher Louise Glück passed away. She was 80 years old. Glück left behind a body of work both fiercely intimate and colossal in scale. Her poetry harnessed a lyrical precision that enabled her to explore the mysteries of fate and family, nature and death, grief and mortality. Threading these varied themes together is Glück’s voice: unmistakably potent yet rhapsodic, witty yet deeply dramatic.

“The poets I returned to as I grew older were the poets in whose work I played, as the elected listener, a crucial role,” Glück said in her Nobel acceptance speech. “Intimate, seductive, often furtive or clandestine. Not stadium poets. Not poets talking to themselves.”

Over the course of a storied poetic career, Glück preserved her straightforward lyrical approach, preferring the unassuming diction of ordinary speech over hyperbole and embellishment.

Her breakthrough collection, The Wild Iris, is set in the midst of conversations between two plants and God. It received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1992.

Likewise, her subject matter, across the years, delved into family relations and marital strife, but also the lives of flowers, the pull of planets, and mythologies. Exploring the fraught depths of private life, Glück’s poetry drew upon life’s different dimensions, forging a path of words forward where there could be none.

In her teenage years, Glück underwent psychotherapy after suffering bouts of anorexia. She would later credit therapy for providing her with a framework to understand the motions of life.

This perspective on life inevitably seeped into her poetry, fueled by dark observations and candid assessments about the nature of life, nature, and fate. Her breakthrough collection, The Wild Iris, is set in the midst of conversations between two plants and God. It received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1992.

She later won the Bollingen Prize for the 1999 work Vita Nova, which focused on the breakup of her second marriage, entwining the mythological and mundane in enrapturing verse. From 2003 to 2004, Glück served as poet laureate of the United States.

In the middle of the pandemic, Glück was awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize for Literature for her poetry whose “austere beauty makes individual existence universal.” All this amount to an unmistakably singular voice in the world of poetry.

Below is a sampling of the beloved poet’s best work.

The Wild Iris

“The Wild Iris,” one of Glück’s most widely anthologized poems, explores the burdens of human grief from the perspective of the titular flower. The poem was initially published in 1992 from the eponymous collection.

At the end of my suffering

there was a door.

Hear me out: that which you call death

I remember.

Overhead, noises, branches of the pine shifting.

Then nothing. The weak sun

flickered over the dry surface.

It is terrible to survive

as consciousness

buried in the dark earth.

Then it was over: that which you fear, being

a soul and unable

to speak, ending abruptly, the stiff earth

bending a little. And what I took to be

birds darting in low shrubs.

You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again: whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice:

from the center of my life came

a great fountain, deep blue

shadows on azure seawater.

Mock Orange

Also one of her most well-known poems, “Mock Orange” highlights Glück’s intense and feverish exploration of desire. In this poem, she draws on all the senses to create an indelible portrait of a highly charged yet private moment.

It is not the moon, I tell you.

It is these flowers

lighting the yard.

I hate them.

I hate them as I hate sex,

the man’s mouth

sealing my mouth, the man’s

paralyzing body—

and the cry that always escapes,

the low, humiliating

premise of union—

In my mind tonight

I hear the question and pursuing answer

fused in one sound

that mounts and mounts and then

is split into the old selves,

the tired antagonisms. Do you see?

We were made fools of.

And the scent of mock orange

drifts through the window.

How can I rest?

How can I be content

when there is still

that odor in the world?

Anniversary

Though known for her austere and reticent poetic voice, Glück also inhabited more witty modes. Meadowlands, her 1996 book-length sequence, featured scenes of domestic and marital conflict, nuanced by an attention to sex, humor, and dialogue. “Anniversary,” a poem from that collection, showcases these preoccupations to humorous effect.

I said you could snuggle. That doesn’t mean

your cold feet all over my dick.

Someone should teach you how to act in bed.

What I think is you should

keep your extremities to yourself.

Look what you did—

you made the cat move.

But I didn’t want your hand there.

I wanted your hand here.

You should pay attention to my feet.

You should picture them

the next time you see a hot fifteen year old.

Because there’s a lot more where those feet come from.