Profit is life. Yes, even in the arts.

I was surprised and embarrassed when someone called me a patron of the arts. I reserve that term for uber rich art collectors and benefactors. I’m none of those.

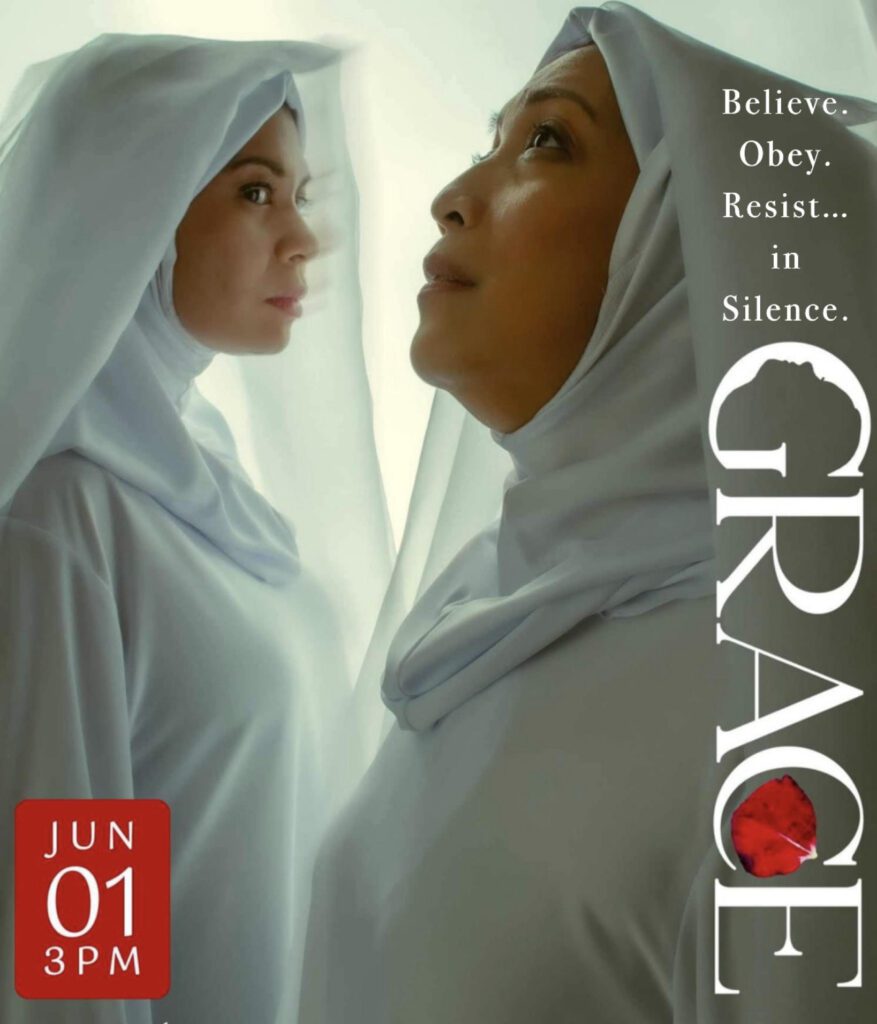

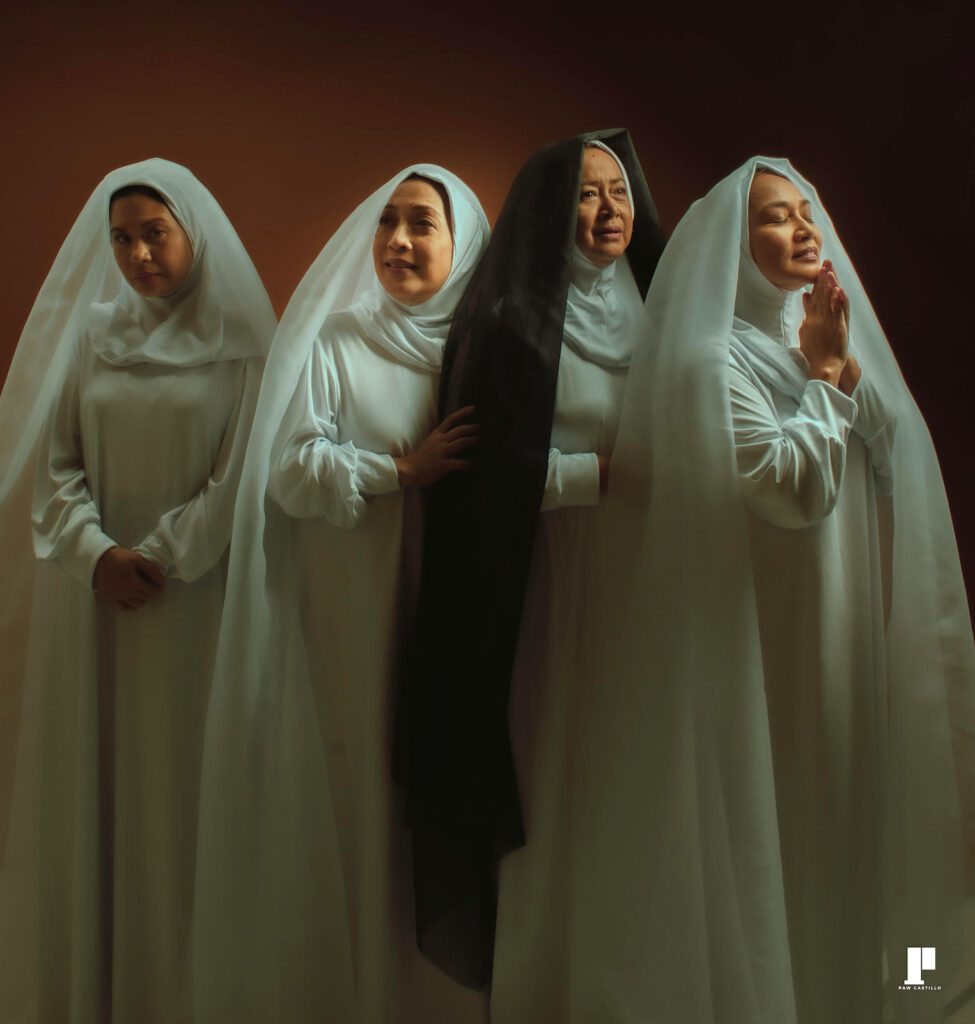

The quip was prompted by the upcoming original stage play Grace, seven-time Palanca winner Floy Quintos’ fictionalized narrative of the so-called Lipa Miracle in Batangas of 1948. More to the point, it’s the third theater production I’ve taken on as a show buyer.

And then I realized that, as a show buyer, I was indeed a patron of the arts. Maybe not in my definition of the term but in the general sense, someone who’s more than a casual supporter.

What is a show buyer? Simply put, it is what the name suggests—someone who buys a show. Buying a show means paying the price tag of a particular show. The amount covers all production and marketing costs incurred by the producer computed at a profit for that specific show.

Show buyers are to theater what block screeners are to movies: they aren’t the producers but they have ownership of the particular show/screening they’ve bought, and they make money from ticket sales.

While show producers have their promotional and marketing efforts to drum up general interest in the shows, show buyers do the actual leg work in selling tickets for their own shows, usually tapping friends, family, and colleagues.

It is, after all, their own money involved and the commercial success of their show—the return on their investment and, more importantly, the profit—depends a lot on how well they harness the clout of personal relationships, if not their pester power.

How show buyers turn a profit

Technically, one show only has one show buyer on paper, the one identified in the contract. There are indeed lone show buyers but there are also groups pooling their resources together to meet the financial requirements. They’re the ones fronted by an official representative whose name and signature are on the contract and who liaises with the producer. The rest of the group are focused on selling tickets and doing the group’s own promo and marketing initiatives.

The number of show buyers in a group depends on how deep their pockets are and, of course, the show costs. Individual shares in the income also depend on the number of show buyers. They are usually split evenly.

Let’s do some sample math. Say a show costs P250,000 and there are five in the group of show buyers, it means each one makes a P50,000 investment to buy the show. If a sold out show equals P500,000, then each show buyer gets P100,000. That’s a 200% return on investment.

Show buyers don’t need to shell out the full amount up front. Payments are usually made in three tranches. The initial 30 to 40% is settled upon signing of the contract for the show. This is what comes out from the show buyers’ pockets. The remaining balance is paid 2-4 weeks and 1-2 weeks before the show. If sales are strong, they can be used to settle the other obligations without any need for the show buyers to cough up more money.

As show buyers, we knew the risks and challenges. We also saw the potential. We put our faith in the artistic team behind the show led by Floy Quintos.

This is the important role of show buyers in the theater industry: they absorb part of the business risks involved in mounting a production. If a show fails to sell enough tickets to recoup the show buyers’ investment, they incur the financial loss and shield the producer from losing money.

That’s a lifeline for the brave few in the theater world that put their moolah where their mouths are. It not only keeps them afloat: more crucially, it makes them profitable.

And profit is life. Yes, even in the arts. It’s especially critical in the local entertainment field, particularly movies and theater where so many producers are serving a small audience, especially for original Filipino works. Profit means fresh money that can be used to fund a new project.

Competition is even tighter in the post-pandemic era in theater where the artists, many of whom are producers themselves, are flexing their creative muscles after being locked down since 2020. It was only last year when the industry reopened wide. It’s like revenge producing to take advantage of theatergoers’ appetite for revenge viewing.

Not all productions have a sellout crowd

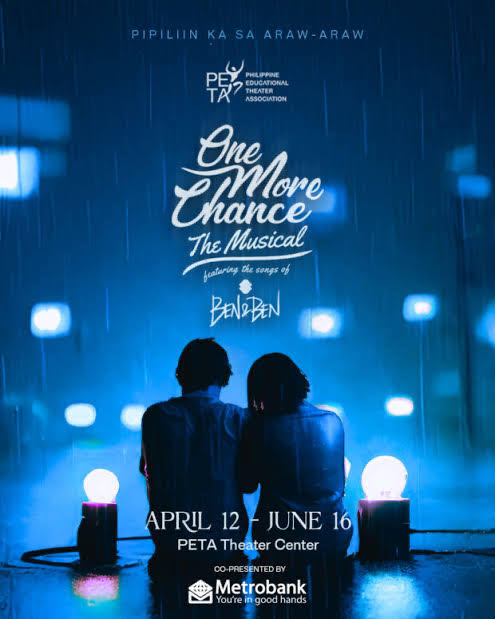

Among original pieces, the musical adaptation of the classic teen TV series Tabing Ilog did not see sold out shows. On the other hand, the musical adaptation of the classic romance-drama movie One More Chance was a certified hit as soon as tickets became available online, with many shows selling out quickly. It also attracted a long list of interested show buyers and not all of them could be entertained and given shows.

Fortunately, my group got a show, the one scheduled for May 24, Friday. We actually preferred a weekend playdate because weekend shows are easier to sell. Tickets sold out anyway—as early as mid-February, in fact. And we hardly lifted a finger. In fact, we have a waitlist of ticket buyers who are ready to take the spots of those who fail to make good on their reservations. But with almost all tickets accounted for, it seems like their wait will remain on paper.

The blockbuster success of One More Chance is a no-brainer. Beloved film + Ben&Ben songs is a winning formula if there was one. And this will most probably be a new formula for Filipino theater.

My first foray into show buying came last year with the period musical comedy Walang Aray. I was invited by a good friend who felt that the show was the right vehicle for his own debut as a show buyer. The two of us technically shared one slot in our show buyer group. It meant we halved the investment intended for one group member. The rules are flexible that way. The more people in the group, the lower the financial risks are per person.

State of grace

This brings us to my third project as show buyer, the play Grace. It’s the riskiest project yet among the three I’ve gotten myself into. It doesn’t adhere to any winning formula. It’s not an adaptation of a well-loved pop culture icon, it doesn’t feature pop music and it’s not a comedy, which is easier to sell especially in the post-pandemic era.

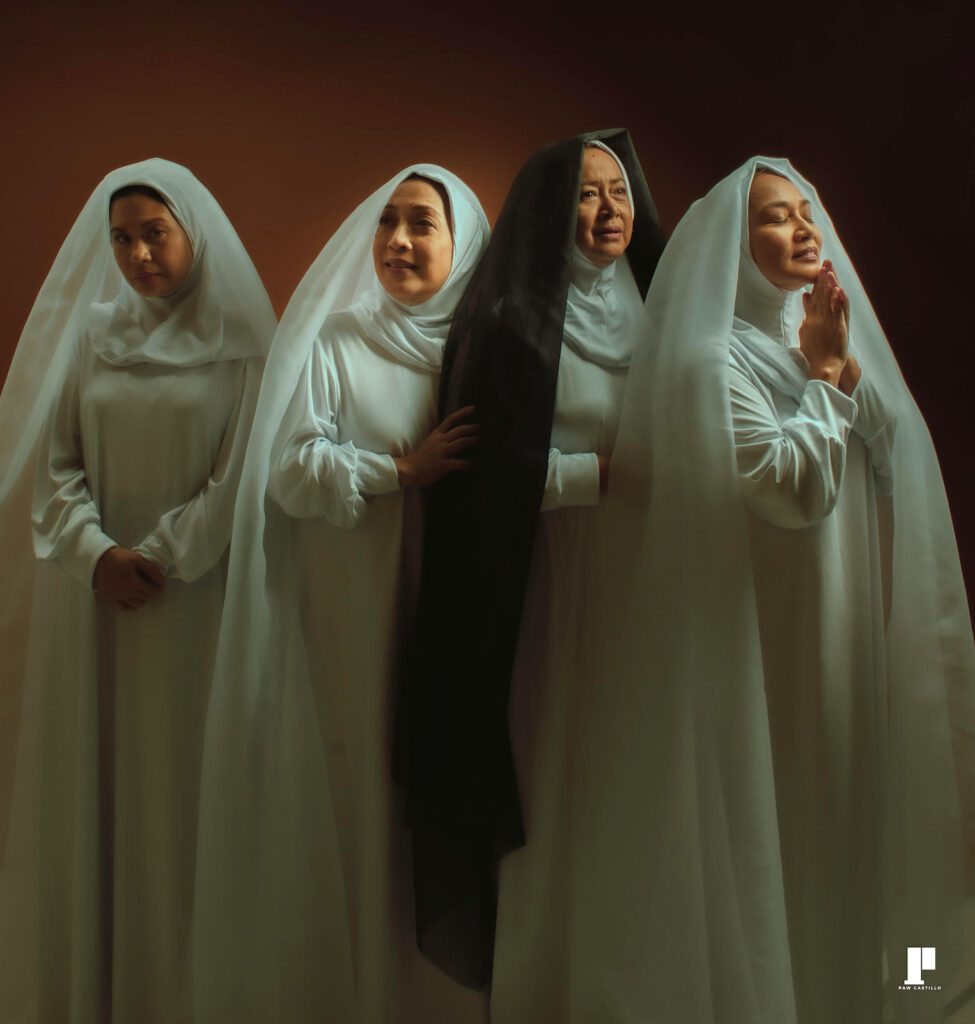

But it does have a selling point, or at least something for people to talk about that hopefully becomes loud enough to move tickets. It’s the play’s controversial subject matter, the so-called Lipa Miracle of 1948 involving a reported series of apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary, who allegedly identified herself as Mary, Mediatrix of All Grace, to a monastery novice and several instances of rose petal showers falling from the sky.

The Vatican declared the events “not of supernatural origins” in 1951. In short, hoaxes. But devotion to the Mediatrix has been steadily growing since the late 1990s, with vocal champions of the Lipa Miracle from the clergy and lay devotees constantly calling for the reopening of the case.

However, the controversy has not been in public conversation for a long time. It only hogged the limelight in mid-March when the official Vatican document containing the negative verdict on the Lipa Miracle was released to the public for the first time ever. Serendipitously, Grace had its official public launch on social media just a few days before.

Thus far, tickets to our show scheduled on June 1, 3 pm, have been selling steadily. It’s nowhere near the speed of Walang Aray, even less so than One More Chance. It’s totally understandable. It would actually be a minor miracle if Grace did brisker business than either of the two other shows.

As show buyers, we knew the risks and challenges. We also saw the potential. And in the midst of these we put our faith in the artistic team behind the show—the same group behind last year’s acclaimed smash hit political comedy The Reconciliation Dinner led by playwright Floy Quintos—to deliver something we can be proud to be a big part of behind the scenes.

I’ve been an avid supporter of Filipino theater for years, raving about shows I loved and recommending them to everyone I know. Last year I went even further and deeper by putting more of my money where my mouth is, moving from paying viewer to show buyer.

And of all three shows, it’s Grace in retrospect, which makes me least cringey with the “patron of the arts” label.

For tickets to Grace, contact 09175112110 or go online at http://bit.ly/GRACE_June1.