From the 16th century to modern times, meet the women who forever left their mark on the art world.

In the history of art, the dearth of information on female artists continues to be a hindrance in fully recognizing the contributions of women. The challenges range from the prevailing social norms that disallowed women from the profession, a documentation policy that refused to recognize women, and even women themselves being pressured to pass off their works as creations of men.

But the reality of female artists cannot be denied. And while their stories are few, many are quite spectacular. Indeed, their achievements have changed the way we see the world.

Caterina van Hemessen (1528-1588)

Caterina van Hemessen is believed to have painted the first self-portrait of an artist while seated by an easel. The Flemish Renaissance painter, like most female artists of her generation, was severely limited in the instruction that she received. Training meant an apprenticeship with a master which required living with them—an unacceptable option unless the teacher is a relative.

Caterina was fortunate to have been trained by her father, Jan Sanders van Hemessen. She achieved success as a portrait artist with her self-portrait being her most famous work. It can be viewed at the Kunstmuseum Basel. Her career was believed to have been cut short because of her marriage.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–c. 1652)

Like Caterina, Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi received her first art instruction from her father, Orazio Gentileschi. Artemisia’s personal life, however, took a controversial and violent turn. After her father, she went on to train with Agostino Tassi who raped her. He promised to restore her honor through marriage but did not keep his word. It was only at this point when Artemisia’s father sued Tassi not for the rape but for reneging on his promise to marry his daughter. She testified in court and was subjected to torture as a method of verifying her testimony. Tassi was exiled from Rome but the sentence was never carried out.

Despite the tragedy, Artemisia emerged as one of the most accomplished artists of her generation. Her father described her as “peerless.” Her earliest surviving work, Susana and the Elders, was the first of a parade of dramatic compositions which blended Caravaggio’s realism with Annibale Carracci’s classicism. She became a court painter of note and enjoyed the patronage of the Medicis and Charles I of England. She was the first female to be accepted to the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno (Academy of the Arts of Drawing).

Artemisia was invited by Michelangelo Buonarroti the Younger to contribute to the ceiling of Casa Buonarroti along with other Florentine artists. She was paid three times more than her colleagues for her Allegory of Inclination.

Italian critic Roberto Longhi described Artemisia as “the only woman in Italy who ever knew about painting, coloring, drawing, and other fundamentals.”

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749-1803)

While Artemisia broke glass ceilings with her many achievements, French painter Adélaïde Labille-Guiard used hers to help other women become achievers themselves. While the history of her art instruction was unclear, it is believed that she studied miniature painting under François-Élie Vincent and was apprenticed to Quentin de la Tour. At 20, she was admitted to the Académie de Saint-Luc which provided the venue for her first exhibition. The show was so successful that it offended the Royal Academy and led to the abolition of all other guilds and similar organizations.

Because the Académie de Saint-Luc was forced to close its doors, Adélaïde applied to the Royal Academy. She was among the very first women to be accepted. She gained the patronage of the royal family and has painted the portraits of many of Paris’ high society. What she created were bold, detailed, and opulent representations of women who were painted facing the viewer directly. The ostentatious fashion with all its complexities allowed her to showcase her talent.

Along with highly prized commissions her reputation was such that she became the first female artist to be allowed to set up her studio for herself and her students at the Louvre. She campaigned for the rights of female artists which resulted in the lifting of the limits of female membership in the Royal Academy as well as allowing them to serve on the institution’s governing body.

Mary Cassatt (1844–1926)

American painter Mary Cassatt was among the next generation of artists to benefit from Adélaïde’s advocacy and the growing movement towards the acknowledgment of female artists. But acknowledgement, Mary soon found out, was a long way from acceptance.

A force of nature during the Impressionist movement, she was described by Gustave Geffroy as one of “les trois grandes dames” (the three great ladies) together with Marie Bracquemond and Berthe Morisot. She hailed from an upper-class family that valued the education, travel and the arts but her decision to become an artist was met with disapproval by her parents. Still, she attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts but was unhappy with the slow pace and the attitudes of the male teachers that she decided to educate herself instead.

She quit and moved to Paris but being female, was not allowed to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. Refusing to accept defeat, she applied to study directly under the masters of the school and was accepted by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Together with Elizabeth Jane Gardner, they became the first two women ever allowed to exhibit at the Paris Salon in 1868. The accepted piece was The Mandolin Player.

It was a rollercoaster ride for Mary – alternating between rejection of her because of her gender and acceptance of submissions because her art could not be denied. At her lowest point, with her father continuing to refuse to pay for her art materials and her works being rejected by the Salon, she received an invitation from Edgar Degas to show her work with the Impressionists. It sparked a lifelong friendship and collaboration.

Impressionism heavily influenced her art. And while most of the group would suffer from the contempt of traditional critics, Mary began to receive more favorable reviews of her work. She created Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge or Science – a mural for the World’s Columbian Exposition. She became an advisor to several major art collectors and was awarded by France the Légion d’honneur in 1904. As she fought for her art to be accepted, she also fought for women’s rights to be recognized including the right to vote.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986)

Mary Cassatt’s advocacy for women’s rights would figure heavily in the art of succeeding female artists including the legendary Georgia O’Keeffe. Dubbed as the Mother of American Modernism, her art was undeniably female and incredibly powerful.

A product of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York City, Georgia consistently topped her class and received awards and citations for her work. Family circumstances and ill health left her unable to pursue a career as an artist, forcing her to take commercial assignments and teaching positions. But her passion for art could not be quashed. Whenever her health permitted her, she would take classes from different disciplines, leading her away from realism and into the arms of abstractions.

Studying, teaching, and creating works that pushed the boundaries of art, Georgia helped establish the American modernism movement. In 1916, she mailed a series of charcoal drawings to Anita Pollitzer who shared them with Alfred Stieglitz. He exhibited the works and changed Georgia’s life.

The couple began a personal and professional relationship and among of the products of this union were the infamous flowers that were literally and figuratively bold in their representation.

The reviews—both positive and negative—elicited passionate reactions from the critics. She pushed back against the sexual interpretations of her work, saying: “When people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they’re really talking about their own affairs.”

She received an honorary degree of “Doctor of Fine Arts” from The College of William & Mary and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. She was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as well. She also received the M. Carey Thomas Award at Bryn Mawr College and an honorary degree from Harvard University.

She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford, and the National Medal of Arts by President Ronald Reagan. In 1993, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

In the ‘30s, Georgia O’Keeffe crossed paths with another artistic giant: Frida Kahlo. While unconfirmed, it was widely believed that the two women carried out an affair. The relationship, however, left a mark on each other’s art. Frida’s infamous self-portrait included flowers that were not native to Mexico and were previously used by Georgia.

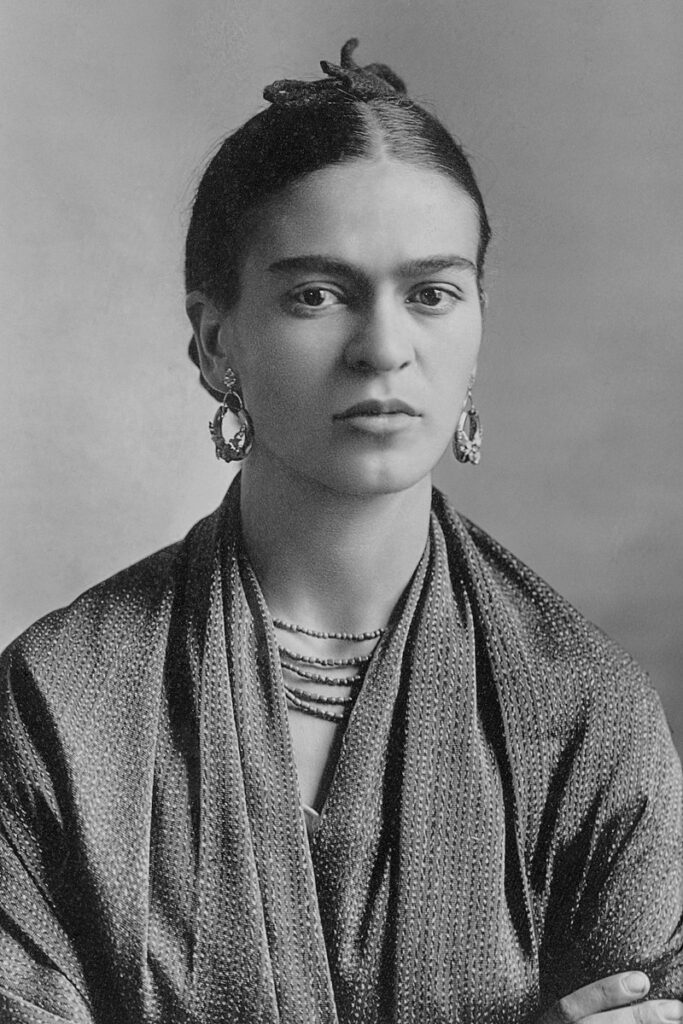

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954)

The Mexican surrealist exploded into the art scene with artworks portraying personal tragedies in the most colorful and imaginative manner. Frida was studying to become a doctor when a bus accident left her injured and in a lifetime of pain. The journey to recovery included indulging a childhood interest in art which eventually became her career.

Artist and printmaker Fernando Fernández was her childhood teacher. Her sketches reeked of talent. When she returned to art after her bus accident, Frida began painting portraits of herself, her sisters, and her friends using a blend of the classical techniques and avante garde styles.

She moved to Morelos in 1929 with her husband, artist Diego Rivera whom he met as a fellow member of the Mexican Communist Party. She fell in love with Cuernavaca and shifted her style to reflect the folk art that surrounded her. Her work caught the eye of Andre Breton who helped her exhibit at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. Its success led to an exhibition in Paris which was less successful but paved the way for a different kind of triumph. The Louvre bought one of her pieces, The Frame, which made her the very first Mexican to become part of the prestigious collection.

Ill-health plagued her and cut short a career that listed many groundbreaking achievements and international recognition. She died at the age of 47.

Frida was on her way to becoming a tiny footnote in the global art history when she was “rediscovered” by art historians, political activists. She became an icon for the Chicano movement as feminism and the LGBTQ community. Today, her life and works are being celebrated as the ultimate expression of the female experience and form.

Yayoi Kusama (1929-)

But if there is anyone who can top the explosion of colors that Frida is known for, it would be Japanese contemporary artist Yayoi Kusama. She is generally acknowledged as the most important living artist of Japan. She is the world’s top-selling female artist. Her work spans the entire length and breadth of visual arts and beyond with her creations including sculpture and installation, painting, performance, video art, fashion, poetry, and fiction.

Born in a seed farm in Matsumoto, Nagano, Yayoi’s dysfunctional family dynamic figured heavily in her art. Her mother disapproved of her art and would routinely take away her drawings to discourage her for pursuing it. Instead, she would be sent to spy on her father and his extramarital affairs.

At 10 years old, she began experiencing hallucinations that included flowers and patterns of fabric coming to life. World War II also influenced her teen years. She was sent to factory to sew parachutes for the Japanese army. Art became her escape.

After the war, she studied Nihonga painting at the Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts. But the strict traditions frustrating and began leading towards the European and American avante garde. She soon began covering her canvases with dots – a direct influence of her hallucinations – which would eventually become her trademark.

She lived in Tokyo and France before deciding to move to the US, describing Japan as “too small, too servile, too feudalistic, and too scornful of women.” She became friends with Georgia O’Keefe and Eva Hesse, and soon made a name for herself as the leader of the avante garde movement. It was during this period that she began producing soft sculptural pieces of everyday objects being covered by phallic protrusions – a direct result of her father’s extramarital affairs and her parents’ dysfunctional relationship.

While Yayoi established a reputation, incidences of other artists being “inspired” by her work left her depressed. Claes Oldenburg began exhibiting pieces that were very similar her phallic protrusion-covered sculptures. After she exhibited a boat covered in soft sculptures with the entire space covered with photographs of the same boat, Andy Warhol mounted a similar show featuring a cow instead. Upset, she became more secretive about her ideas and creations.

Her years in the US, however, were extremely productive and gave birth to her Mirror/Infinity rooms. But as her work became larger than life, she found herself profiting less from her art. Overworked and frustrated, she attempted to take her life.

She bounced back and created more complex installations. But her return to Japan was met with indifference. She fell into depression and once again attempted to commit suicide. Realizing how precarious her situation was, she voluntarily checked herself into a hospital and has lived there ever since. She established a studio just walking distance from the hospital.

Today, she has reestablished herself in the global art scene with a collaboration with Louis Vuitton among her most recent large-scale installations. Still struggling with her mental health and the demons of her past, Yayoi continues to use her art to relieve the pain of her illness.