Dr. Angelita Legarda’s 1978 article drives the value of a certain barilla to over a million pesos.

In our roundup of items of interest at the LeónExchange Online Auction, we listed the Philippine barillas—the ancestors of our coinage and the origin of the Filipino term “barya” (loose change). We also noted that their limited circulation during the 18th and 19th century could further stamp the artifacts’ historical significance to collectors or numismatists (coin specialists).

True enough, one of the barillas set the record for the most expensive coin ever sold in the Philippines. León Gallery reported that it was only less than five minutes into the introduction of Lot 118, an 1899 barilla, when its initial value of P50,000 ballooned to P1.4 million—29 times its original price.

Investment banker Sandy Lichauco—who is also an antique and history buff—shared in an interview with León Gallery that the historical value of the 1899 barilla puts it above the other coins (dated 1722, 1730, 1731 and 1740) that were up for auction. “[T]his particular barilla was suspected to have been used specifically for a particular area at a very important time in our history: at the time when General Lawton won the battle of Laguna de Bay and the need for small change had to be addressed,” he said.

Lichauco noted a certain Dr. Angelita Legarda’s 1978 article on the coin in Barrilla, the quarterly monograph of the Money Museum of the Central Bank of the Philippines (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas), is the sole source of information on the 1899 artifact. “[At] the same time she had received this specific coin from a collector. So again, the historical value and strength of the provenance of the coin [is the reason] why it ‘outperformed’ the other coins in the auction.”

That these coins survived several wars and natural disasters is a miracle in itself; that accounts have been written about their possible use, however scant, is a historian’s (and history buff’s) delight; and that a short passage in the aforementioned account would drive the coin’s value to over a million pesos is a marvel. This only brings us to ask: who is Dr. Legarda?

By profession, Angelita Ganzon de Legarda was a medical practitioner; however, she was also an expert in numismatics. She was the first director of the Money Museum, which was established in 1974. Economist and professor emeritus Dr. Gerardo Sicat recounted in an issue of The Philippine Review of Economics that it was Legarda’s husband, former central bank deputy governor Benito Legarda, Jr., who suggested to then-governor Gregorio Licaros the idea of building such a facility:

“Economic history and central banking at least could intersect in an interesting way in the story of how economies grow. An idea that Benito Legarda thought interesting was to have a museum that provided a narrative of how commodity money like useful products, metals, gold and jewelry like gold trinkets evolved into coinage and other forms of money and how different kinds of paper money developed as means of payment in all economies. It was Benito Legarda who suggested to Governor Gregorio Licaros the idea of a money museum. Thus, the Money Museum was born in 1974,” writes Gerardo P. Sicat in “Benito Legarda, Jr.: in his own words and an appreciation” from The Philippine Review of Economics.

Concurrently, from 1977 to 1978, Legarda was also the president of the Philippine Numismatic and Antiquarian Society, a group that seeks to “promote the science of numismatics and antiquarianism through the study and collection of coins, paper money, medals, stamps, books, documents and other antiquities.” They also “showed great concern for the preservation of cultural heritage and the promotion of the Philippine numismatics, history and culture throughout the world for many future generations.”

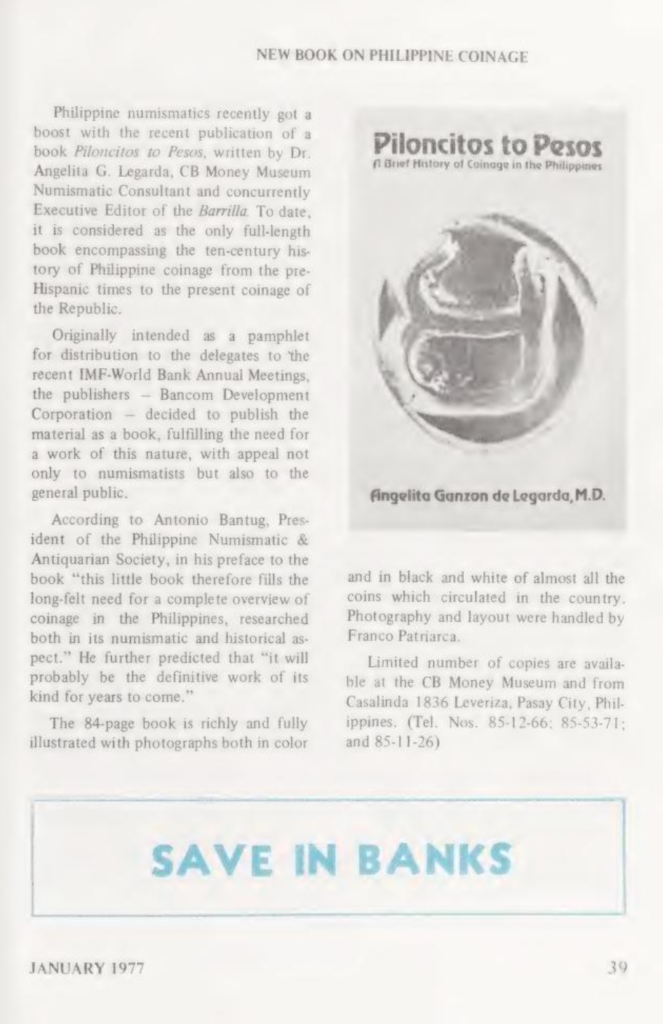

One of Legarda’s valuable contributions to Philippine numismatics is the book Piloncitos to Pesos: A Brief History of Coinage in the Philippines. Published in 1976, the text begins its survey from pre-colonial currency (piloncitos are small, bead-like gold pieces that were used as currency) to the Philippine peso of the ‘70s. Among numismatists and Filipiniana book collectors, the tome is a rare find and a valuable resource, so much so that most academic texts and journals that touch upon Philippine and/or Southeast Asian currency refer to Legarda’s book.

In a few issues of Barrilla in the late 1970s, Legarda wrote articles on the origins of and the possible uses of excavated barillas from Laguna, which she received from a collector in 1978. It was from the province that many of the first piloncitos were excavated, driving the hunt for more artifacts at the time. Numismatists, collectors, and those wanting to sell possibly valuable wares focused their efforts in rivulets within the town of Siniloan.

It was also within Laguna that the P1.4 million 1899 barilla was rediscovered. Legarda noted that the coin’s visual cues, including an “L” that may have stood for “Laguna;” “RF,” which may have meant “Republika Filipinas;” and the “1899” date (which denotes the coinage’s minting and use during the Philippine Revolution), point toward this specific barilla’s link to General Henry W. Lawton’s triumph in Laguna De Bay after the capture of Malolos.

Forty-five years after, Legarda’s receipt of the barillas (León Gallery has a copy of a memo of receipt dated June 7, 1978, issued by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas’ money museum and signed by Legarda herself) and her writings on the coinage have been responsible for the staggering sales of the barillas. Aside from the P1.4 million lot, a pair of barillas from 1731 and 1740 sold for PHP 793,056; a 1732 barilla went under the hammer for PHP 552,736; and a 1722 barilla racked up PHP 444,592.

Moreover, these historical documents further verify the authenticity of the lots. Interestingly enough, it was Legarda herself who already identified the consequences of hyping the value of these artifacts. In Barilla Vol. 5, No. 1 (1978), she wrote:

““It is unfortunate that the extremely high prices paid for the early specimens which appeared on the market led to the surfacing of so many more ‘unique’ and ‘formerly unknown’ pieces that the serious numismatist is at a loss to evaluate these many ‘finds.’ It would have been easier perhaps to tell between the genuine and the spurious if prices for these specimens had been held down initially. In today’s numismatic market, with thousands of pesos at stake for ‘unique’ or ‘extremely rare’ pieces, the temptation to manufacture these pieces of metal with crude designs may be too much to pass up.”

After all, counterfeit money isn’t just a problem for current use, but also among collectors, auction houses, and galleries, and Legarda warned readers about such possibilities surrounding the barilla as early as the ‘70s.

However, with her painstaking work and documentation, Legarda has ensured that the integrity of these coins won’t be a problem for León Gallery and the lucky bidder for Lot 118.